Architects and Architecture of London

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080942018…

448 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

AI

AI

The book explores the relationship between architects and the city of London, emphasizing the city's historical and dynamic nature. It reflects on the contributions of significant architects who have shaped London's landscape while also attributing a life and intelligence to the city itself. The text illustrates how London's evolution is tied to its historical context, specifically its Roman foundations and the influence of the River Thames, which has been a central aspect throughout its development.

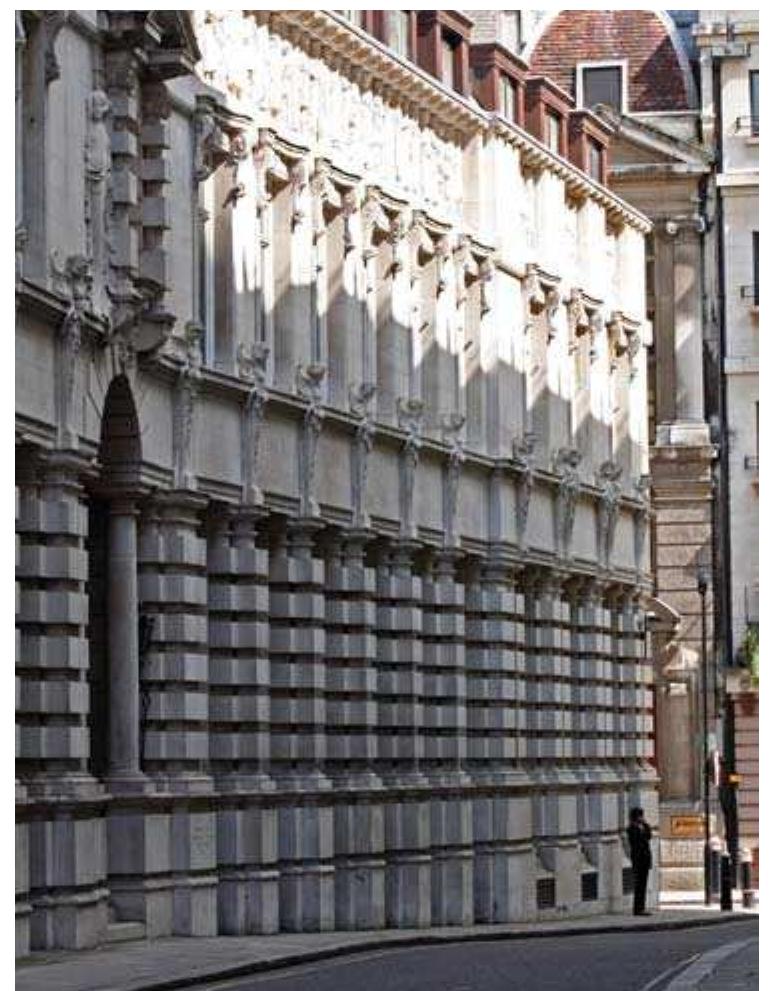

![Such pragmatism had another aspect: an awareness that the ambitious architect of the day needed to promote himself through publications. In addition to That opinion and its orientation toward all that is customary might well have been applauded by the Parisian architect Claude Perrault, some one hundred years earlier, but it was rather ironic in the context of rivalry with the Adam brothers. However, Chambers was also to wrap these reflections in a nascent professionalism that was then beginning to emerge. He not only called upon architects to be “well versed in the customs, ceremonies, and modes of life of all men his contemporaries” (so that he might effectively provide for their requirements), [but also to be] as well as skilled in accountancy, estimating, politics and the like.”](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37903780/figure_093.jpg)

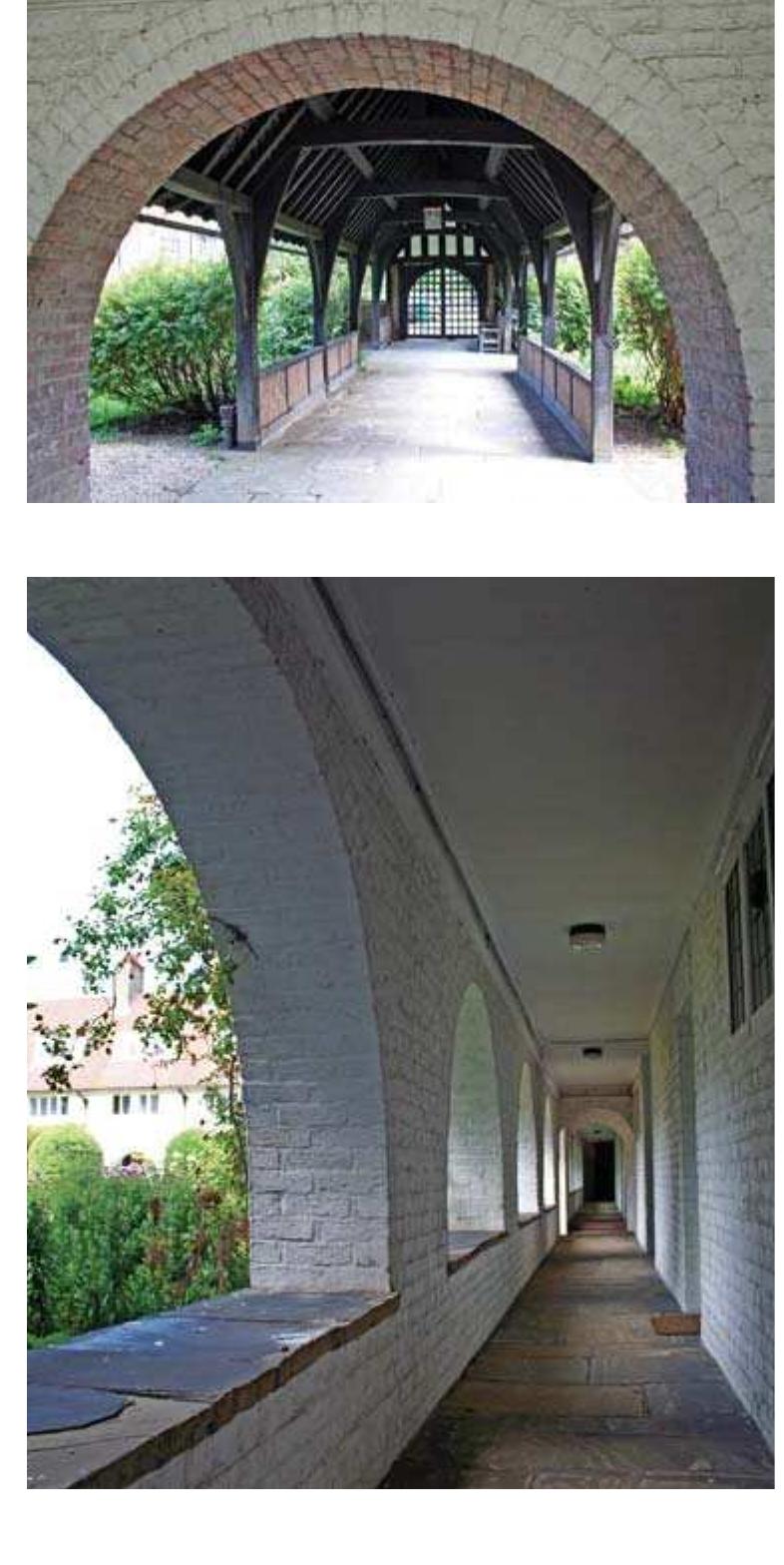

![Lubetkin made several exploratory trips and, in 1931, was even offered the commission for a private house in Hampstead (which proved abortive). However, in 1932 — together with six harvested graduates of the Architectural Association — he formed the Tecton partnership. He was, of course, the dominant partner. John Allan, Lubetkin’s principal biographer, tells us: “His belief in building design as an instrument of social progress was underlaid by a profound appreciation of architecture’s rational disciplines and emotive power. His Marxist convictions and his experience of the Russian Revolution implanted high expectations of architecture's role in transforming society, both through the provision of new and relevant building types — ‘social condensers’ [a distinctly Cedric Price concept] - and through its aesthetic capacity to project the image of an oncoming better world. Lubetkin’s buildings were characterised by clear geometric figures, technical ingenuity, and intensive functional resolution. He dissociated himself, however, from the contemporary doctrine of functionalism, and](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37903780/figure_343.jpg)

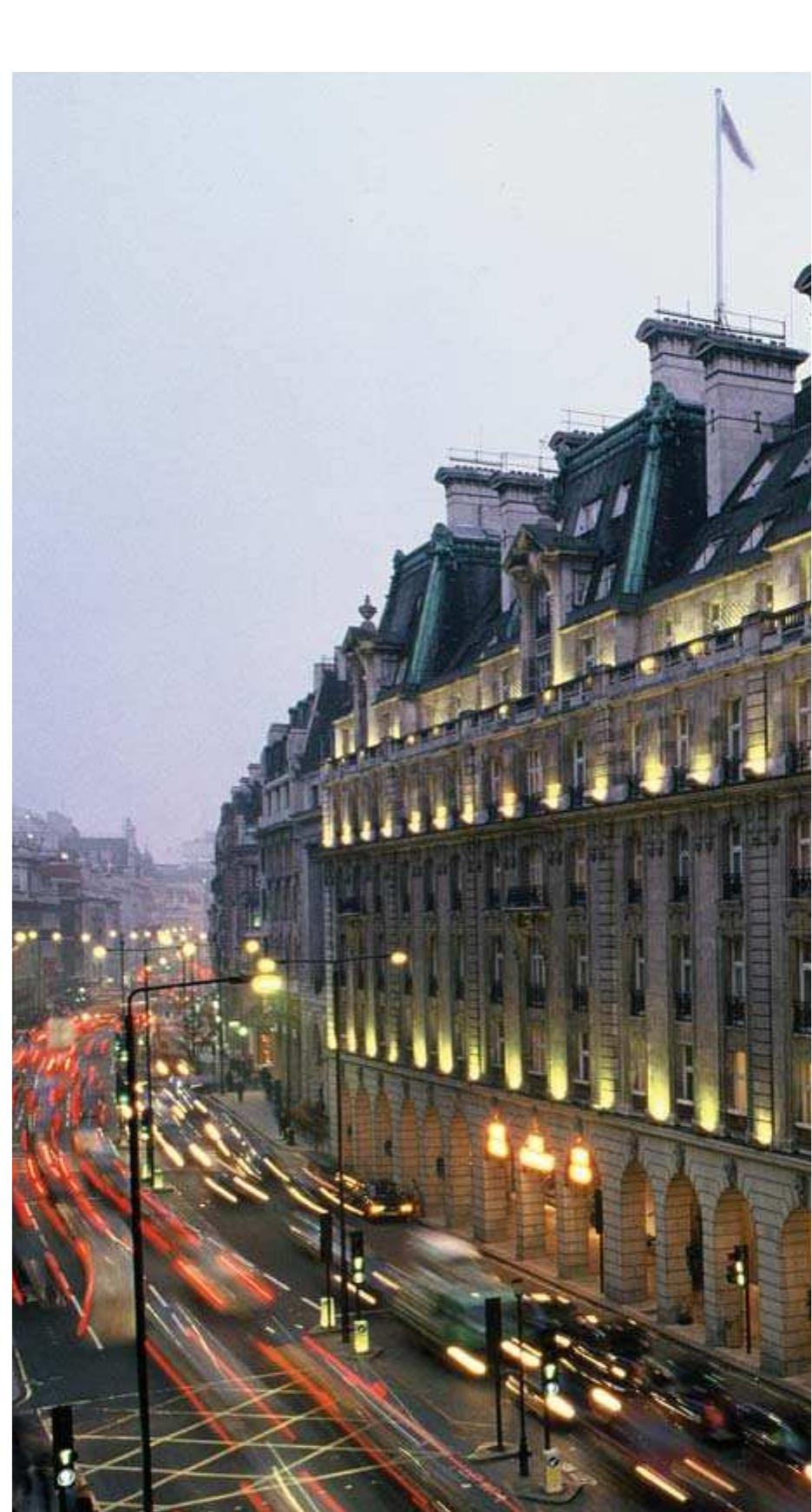

![Above: the bar at the Royal Festival Hall, from the official record, 1951. Regrettably, the recent refurbishment by Allies & Morrison filled-in this dropped area around the bar which had a peculiarly strong impact upon surrounding areas (health, safety and disabled access is quoted). Above: the bar at the Royal Festival Hall, from the official record, 1951. Regrettably, the recent refurbishment by Allies & Morrison filled-in this dropped area around the bar which had a peculiarly strong impact upon surrounding areas (health, safety and disabled access is quoted). ndrew Derbyshire, once a well known post-war English architect, reminisced that, “When | left the AA [the prestigious Architectural Association School of Architecture] in 1951, fired with enthusiasm to build the welfare state, | sought, like most graduates, to join the public service. We thought of private practice as money-grubbing, unfitted to pursue the ideal of social architecture.” Similarly, Ron Herron, a member of the Archigram group, another well-known and respected architect of the ‘60’s and ‘70’s, went to meet his maker proudly knowing that he had never worked for a speculative developer. And one of the more prestigious figures of those years, Leslie Martin, appears to have built upon his success at the Festival of Britain in 1951 by taking on large planning consultancy projects and handing on their development and execution to young architects he worked with in his studio and at](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37903780/figure_361.jpg)

Related papers

The Journal of Architecture, 2016

The Good Metropolis, 2019

Architecture has always been engaged in a dialogue with the city--a relationship often dominated by tension. The architectural avant-garde in particular is commonly understood in its opposition to the existing metropolitan terrain (architectural form vs. urban formlessness). This book, however, unearths strands of thought in the history of 20th-century architecture that actively endorsed and productively engaged with the formless metropolis. Revisiting early experiments that question the city/architecture dichotomy, Eisenschmidt reveals how the formless metropolis has long been a prevalent force within architectural discourse. The works analyzed span almost an entire century: They range from August Endell's urban optics and Karl Scheffler's metropolitan architecture in Berlin, through Reyner Banham's motorized vision of Los Angeles and Situationist performances in Paris, to OMA's city architectures and Bernard Tschumi's cinematic urbanisms. The author constructs new narratives that reposition architecture vis-à-vis the city, by exposing hidden histories. He uncovers architecture's continuing interest in the formless city and elucidates our current fascination with and anxiety about ongoing urbanization, revealing the "good metropolis" that was there all along. Reviews: "The Good Metropolis brilliantly explains how the formless, unpredictable, unknowable, and out-of-control metropolitan condition--seemingly the assassin of architecture and of "the good city"--became an exhilarating resource for architecture (think of the enormously influential work of Rem Koolhaas's Office for Metropolitan Architecture, for example). Moreover, the book's deep scholarship of Berlin reinstates that city as a veritable laboratory of modernization, alongside London, Paris, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, in effect combining two long-needed studies into one." Simon Sadler, University of California Davis "Modern urban history frequently grounds the postmodern recognition of the city's indeterminate dynamism in earlier planners' failed efforts to wring rational and geometric order from the rough currents of industrialization, rapid technological change, and unprecedented demographic growth. The Good Metropolis presents an alternative trajectory: a searching determination on the part of key figures over more than a century to see in the alleged chaos of the city alien and potentially productive orders otherwise impossible to envision. In this theoretically crisp and elegantly written essay, Eisenschmidt identifies the generative tradition of urban inquiry that designers forged to come to terms with, and to learn from, a human creation beyond human comprehension: the modern city." Sandy Isenstadt, University of Delaware

Radical Philosophy, 2005

History Workshop Journal, 1988

Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies, 1999

Diálogos: revista del Departamento de Filosofía, Universidad de Puerto Rico., 2020

The current pandemic forced restrictive measures upon the population’s way of life and spatial confinement of citizens in their homes. This summons urban thought to reflect about the present but also, or mostly, the future of the cities. I will grasp this opportunity to draw a few lines of flight that depart from the streets’ silenced rhythm, and to deal with relationality as the city’s own constitutive matter. Cities are usually thought in a dualistic mode (understood as oppositional or even as an ontological dualism), and they actuallygather different elements: physical city, discursivity, human, non-human, subjectivity, sensitivity, body. To take into account this relationality and its current outbreak from invisibility (like a virus), can help transform and diversify theoretical and practical perspectives on the cities, where the majority of human population is currently living.

The ongoing discussion on the privatization of cities primarily focuses on the controlled spaces of gated communities in the outskirts just as in inner city neighborhoods. However, the physical gating of neighborhoods is increasingly being replaced by other, soft forms of inclusion and exclusion. Not being physically gated or walled has become one of the Unique Selling Points of communities designed according to the concepts of new urbanism. The production of hegemonic urban spaces in these areas is accomplished by tight regulations on the physical environment and “declarations of covenants”, stretching beyond the public governmental realm and into the control of personal lives. More subtle forms of control have evolved and have been transferred to privatized public spaces of inner city areas. The paper puts the discussion forward by extending the discursive context of soft urbanism to the strengthening strategic role of urban governments. The Historic City Center of Vienna serves as an example of converging policies set in effect by private actors and the city administration. In contrast to a privatization of the public realm, in the Historic City Center of Vienna power relations are continuously shifting towards the institutional networks of the municipality, becoming the major player, developer and investor in the production of the meaning, the narrative and the affects attached to the Historic City Center. The tightening regulations for the Historic City Center indicate a programmatic convergence between the concepts of new urbanism and regulations, enacted by the urban government. Empirical analyses, presented in the paper, reveal how power and control are increasingly exerted over residents, private entrepreneurs and private developers alike. The analysis is based on different multi-scaled approaches. The introductory section examines the accelerating deployment of regulations and control. General codes and directives are increasingly supplemented by more detailed, small-scale guidelines just as their objectives are shifting towards the production of ambience based on the thematic production of the city’s narrative. Akin to privatized urban spaces, power is exerted by the cultural reproduction of the Historic City Center, reducing the discrepancy between the imagined and the real city. The mediated translation of power is examined in the second section, critically dissecting the conceptualization of downtown redevelopment projects. Social control and control of social interaction are becoming unfolded by the continuous negotiations of the urban stakeholders. The incremental closing down of options in the public realm is supported by empirical data on the changing economic, social, cultural and institutional assets attached to the Historic City Center of Vienna. The urban functions of the city center follow the new urban form. The third section refers back to the broader conceptual framework of urban renaissance. The re-definition of the strategic function and power of the municipality in the context of urban renaissance is scrutinized in terms of power enacted by constraints of economy and globalization and raises the question of alternate solutions. References: Allen J., 2006, “Ambient Power: Berlin's Potsdamer Platz and the Seductive Logic of Public Spaces”, Urban Studies, Vol.43, No.2, 441-455 Bodenschatz, H., 2005, "Vorbild England: Urban Renaissance in Birmingham und Manchester", kunsttexte.de, No. 3/2005, 18 p. (http://www.kunsttexte.de) Fassmann H., Hatz G., Patrouch J. F., (2007), “The Historic City Today”, in Fassmann H., Hatz G., Patrouch J. F., 2007, Understanding Vienna. Pathways to the City. Münster-Hamburg-Berlin-Wien-London-Zürich, LIT Verlag Füller H., Marquardt, N., R., 2007, " Soft Urbanism: Safeguarding the private city", research network: private urban governance, Paper No. 043, 11 p. (http://www.gated-communities.de) Hatz G., 2007, “Struktur und Entwicklungstendenzen der Wiener City“ in: Kretschmer I. (ed.), Das Jubiläum der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. 150 Jahre (1856-2006, Wien, Österreichische Geographische Gesellschaft

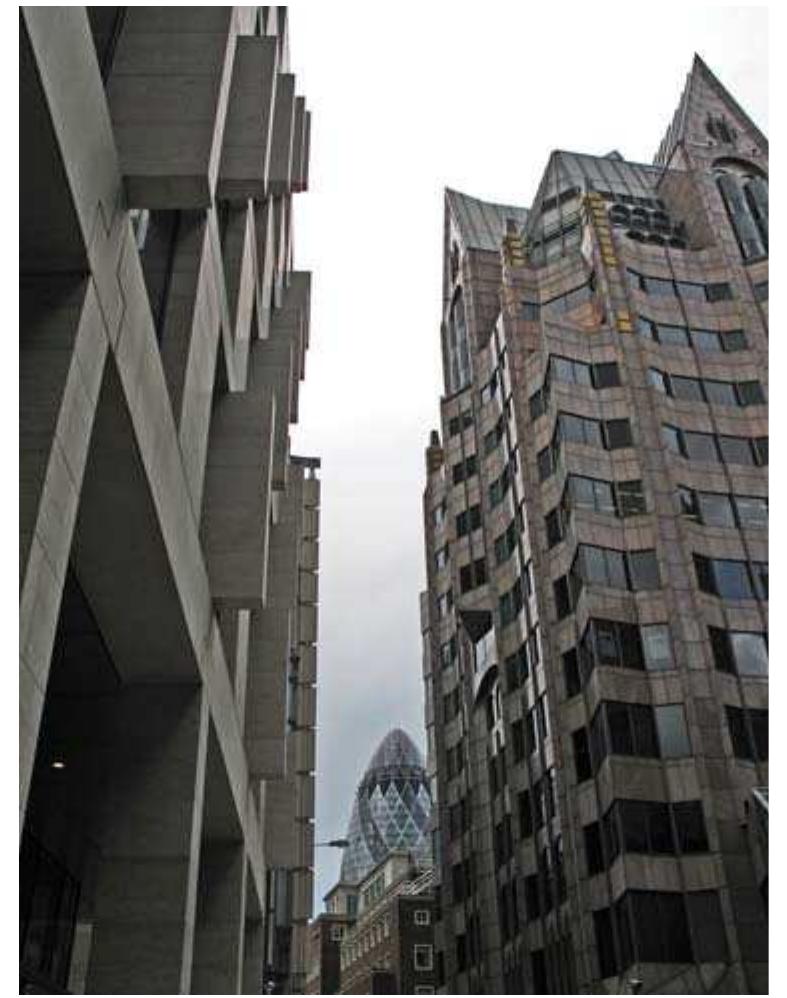

How can we critically engage with capitalism in the 'urban age,' at a time when more and more people live in cities? How can we do so with regard to the built environment of a global city? I distinguish between two different approaches. The first starts from contradictions of capitalism such as the juxtaposition of overabundance and poverty and examines the ways in which these are represented in the cityscape. The second starts from a detailed exploration of practices of city making in order to explore the multiple different and often unexpected ways in which capitalist economies are justified and embedded in texts and images that are deemed to be socially meaningful. In other words, the first develops a critique of the capitalist city; the second allows a critique of capitalism through the city. These two approaches interrelate and overlap. However, their claims and scopes are not the same. Both have unique starting points and different directions of critique. In this essay I discuss these two approaches with regard to London's current tall building boom. At the time of writing, approximately 400 skyscrapers are in the planning stage or under construction in the city. Between fifty and eighty of them are towers that will be built by private developers not exclusively but to a large extent for industries that are pivotal for financial capitalism: banks, insurance and real estate companies as well as globally operating business service firms. These buildings are amongst the most visible manifestations of finance capital. Several of them are located in the City of London, which is London's historical core as well as a commercial center of Greater London. This essay, then, explores the relationship between history and financial capitalism or, better, the ways in which historiographical approaches are related to a critical engagement with urban processes under financialized capitalism. Put differently, I examine the ways in which urban historians criticize the visual impact of office towers on the historic built environment.

Related topics

Related papers

University of Toronto Quarterly, 2004

Public Culture

The concept of the city as a territorial and political form has long anchored social thought. By the twentieth century, the city figured prominently as a laboratory for testing modern techniques of governance. In the twenty-first century this discourse incarnates anew in visions of future mega-and smart cities. Then, as now, cities-as signs of the modern-are the elephants in a room full of adjacent concepts such as the state, the market, citizenship, collectivity, property, and care. This issue picks up a thread from the 1996 special issue and 1998 book of prizewinning essays on Cities and Citizenship (edited by James Holston and Arjun Appadurai). The contributors focused on the role of cities in the making of modern subjects by attending to associations between urbanism and modernity and thus with imperialism, colonialism, and extraction. Now, we reconfigure that line of inquiry to consider Urbanism beyond the City while bearing projections of the future in mind. The United Nations projects that by 2050, two-thirds of the global population will live in cities or other urban centers. But this new density will be greatest in a small number of countries, none which are in the Global North (United Nations 2018). Yet even as cities take unprecedented forms without discernible limits, spatial theorizing continues to invest in a particular concept of the city and to expand that concept's reach into other areas of study, planning, and investment (Amin 2013). Spatial professions capitalize on the city's capacity for generating complex intersections of social, economic, and political forces. Theorists attribute a capacity to distinguish among divergent possibilities mingling unpredictably to the urban apparatus (Martin 2017). Even critical methods remain attached to the idea that cities-whether as infrastructures, instruments, or morphologies-anchor a very particular sense of social life. As Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (1994: 4) noted, philosophy coincides with the "contribution of cities: the formation of societies of friends or equals but also the promotion of relationships of rivalry between and within them." We position the concept of the city by treating it as a "friend" accompanying us through the journey presented in this special issue.

Article, 2025

According to the UN-Habitat 2020 Population Data Booklet, the world population living in the existing 1934 large metropolises is 2.6 billion people: one-third of the world's population. By the year 2050 will be 66% of the world population living in cities. There are 8936 intermediate cities in the world and urban agglomerations today occupy 7.6% of land mass of the planet. These data are alarming due to the density of construction, the consumption of resources, emissions into the atmosphere, the amount of waste and a long etcetera that they imply. However, beyond all those factors that today are "integrated" into the "planning" of the city, there is the failure of architecture and urban planning, which around the world is evident in the daily lives of people, every time that, in contemporary urban conglomerates, the intersubjective relationship of their inhabitants, with the environment and among themselves, is almost impossible for the exercise of a truly free, fraternal, fair, equitable and happy life. Therefore, I call for a deep reflection on what I consider should be a return to the Architecture of the City and on the possible extinction of urbanism.

2008

This important book revives core issues from age-old albeit recently half forgotten debates over urbanity, its problems and advantages. The author suggests that the city concept itself is ripe for being transcended, socio-material condensation serving as its successor. He further outlines a dialectics of today's hardships and comforts of city/condensation life, in the grand tradition of a Howard (1902), Mumford (1938), Le Corbusier (1935), or a Williams (1973). To-day's condensations are analysed as socio-material sediments, each with its political code. Sartre's thinking is the main theoretical basis. A number of hardships and their remedies are discussed and a proposal for reform outlined. As important, a whole family of new concepts are put to use, e.g. the sub-individual, the imaginary.-We analyse the local reviews of the book as a "howl of hurt habitus": While most objections are repudiated, we

Journal of Historical Geography, 1982

the handmaiden of private property interests. At the end of the book Sutcliffe points out that town planning provided a resolution of public and private interests that had counterrevolutionary implications : The years 1890-1914 were a time of growing social tensions in which the idea ofrationalizing the structure of cities acquired an unprecedented appeal. If lower rents, better housing and richer community facilities could remove the need for a major redistribution of income or wealth, then urban planning had a great deal to offer the middle and upper classes in addition to the simple creation of a pleasant urban environment. This is a provocative statement and an antidote to the complacency of much planning history but although implied in parts of the main text it remains a hypothesis tagged on to the end of the study not a conclusion to it. The issues Sutcliffe raises here about social and ideological control are clearly central to an adequate understanding of town planning and need to be argued through with close attention to particular planning projects, to details of economic and social developments and also to the current theoretical debate among historians on bourgeois hegemony. The theoretical implications of Sutcliffe's book are considerable, particularly on the question of the role of the State, but it is for others to pursue them. Sutcliffe's only theorizing-on the spread of planning ideas-is a mixture of art criticism, psychology and economic history and is the least convincing part of the book. But it did yield two delightfully absurd examples of international influence: the Teutonic turrets of Hampstead Garden Suburb and the "Beautify Bolton" movement. The originality of Sutcliffe's study is its international perspective. Its strength is a lucid and scrupulously researched reconstruction of the mentality of the early movement and here the author conveys something of the excitement of town planning before disenchantment and cynicism set in.

Prior to the Second World War Europe’s ruling classes had no perception of the destiny of the modern city. This despite the fact that almost a century earlier Baudelaire had intoned the decadence of their most beautiful city. Proud of their ordered, authoritative, and often authoritarian capitals, Europeans saw history as a course predestined to create that miracle of civilisation exemplified by the metropolis of the old continent: wealthy, with a rigid social hierarchy, symbolically, physically and culturally rooted in history, firmly established at the summit of a providential, though still highly dramatic process. The metropolises of Europe were perceived, in the end, as organisms at the pinnacle of their conscious maturity and the height of their industrial and financial might. They appeared to posses an ability to self-regulate internal and external conflicts, imposing models of assimilation and reciprocal adaptation upon sources of imbalances, conceived by imagining the possible effects of disturbances and anticipating their transformations – thus adopting planning in the form of a series of direct systematic operations. Two years later, in 1939, Claude Lévi Strauss went much further; his direct experience with São Paulo, Brazil (and New York) convinced him that the modern metropolis, which he observed and which observed him with a thousand hidden eyes as he, a foreigner, crossed it, cannot be judged according to the parameters of architecture (thus also excluding those of planning), but with those of the landscape; and to the same degree that everything in the natural landscape is in transformation, simultaneously luxuriance and putrefaction, he claimed that «the cities of the New World […] pass from first youth to decrepitude with no intermediary stage». With no intermediate stage: this is the most important clue, the tag that for the great anthropologist implicitly, though peremptorily, invalidated the idea that the cities of the New World are truly part of history. Lévi Strauss, who certainly learned to be a narrator of cultures and ethnographic contexts as Walter Benjamin learned to be a narrator of cities, froze – despite being captivated – in front of the metropolises of the New World, home to a coexistence between past and present, and between proximity and distance. Perhaps the time has come to truly study the world’s metropolises as individuals in the midst – or at the beginning – of their evolutionary age seeking to establish their stage of development and that of their parts, in the concreteness of reality. The term stage is used here to refer to a recognisable and well-characterised structure that is organised and relatively balanced – equivalent to one of the stages of Jean Piaget’s theory of development. This would make it possible in the most appropriate terms to solicit different urban communities to autonomously imagine the effects of on-going disturbances, accompanying them as they realistically express their fears and desires and anticipate the form and objectives of tangible operations to be implemented within the limits of a community’s available resources and level of organisation and the pedagogic capacities of the city and its government.

Having recognized the city as transcending its physical mores and emerging as more than a mere setting and backdrop for the story to unfold, this essay sets out to show that characterizations within three selected texts produce an aggregated and calculated image of the city which mirrors the psychological and sociological burdens of the 21st century. Further anchoring the essay are the chameleonic perspectives of a city and making a case for how a city’s depiction can be used to expound on the sensitivities of its characters.

London and Manhattan constitute unique urban configurations which have claimed and conquered the metropolitan vision. This paper travels back in time to look for the foundations of these cities’ architectural and urban morphology. The study is focused on the architecture of the everyday, the vernacular buildings which collectively form the character of a city’s historical built environment. It discusses how both preconceived frameworks and emergent architectural decisions and societal rules have shaped the two cities throughout their spatial histories. Drawing evidence from historical and empirical data the analysis presented in this paper builds on space syntax research which investigates morphological processes in urban configurations. The paper looks at two contrasting cases of urban grids to contribute to the understanding of the way different spatial arrangements influence city form. The urban past of London and Manhattan is considered in terms of planning intentions, architecture, urban form and the embodied socio-cultural models and ideals. The approach emphasises the way architectural and urban scales were configured together to produce each city’s historical morphological identity and spatial culture. This stems from an effort to form a parallel understanding of both the building unit and the urban realm where this is situated. In this perspective, the discussion provides an overview on the one hand, of the building aggregation rules of the London terraced house and the Manhattan row house schemes; and on the other hand, the structure of the urban grid in each case. The aim is to shed light on the interplay of these two elements, underlining the challenge for any urban design approach: to tackle both buildings and streets along the lines of a unifying and diachronic spatial logic. The study considers the syntactical and morphological properties of urban space, looking at the building, the block and the city scales. The paper aims to highlight that both for London and Manhattan there exist inherent cross-scale organisational consistencies that hold the spatial cultures of each city together.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.