Biochemical Pathways.[1999 EN].G Michal OCR

…

285 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

AI-generated Abstract

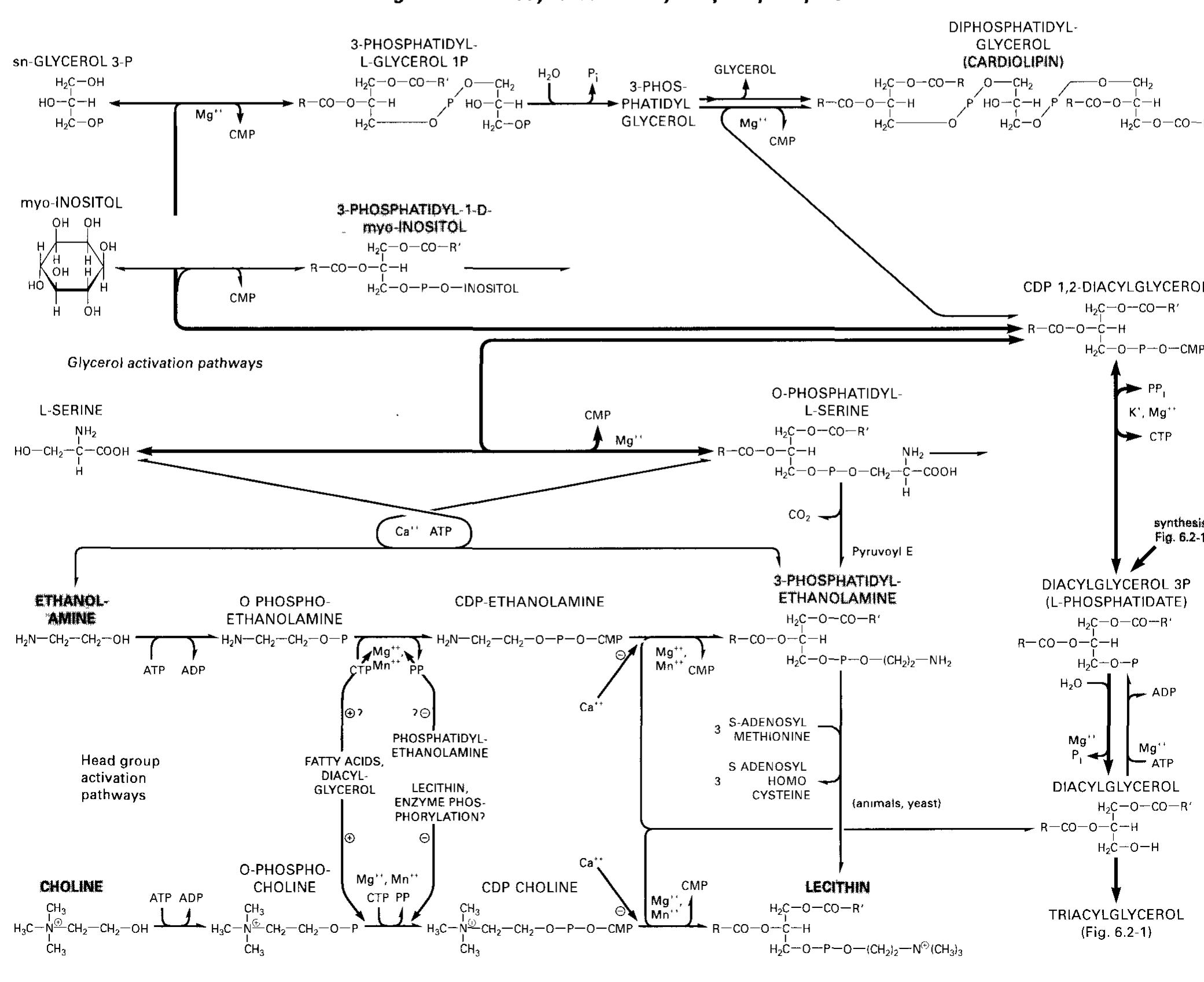

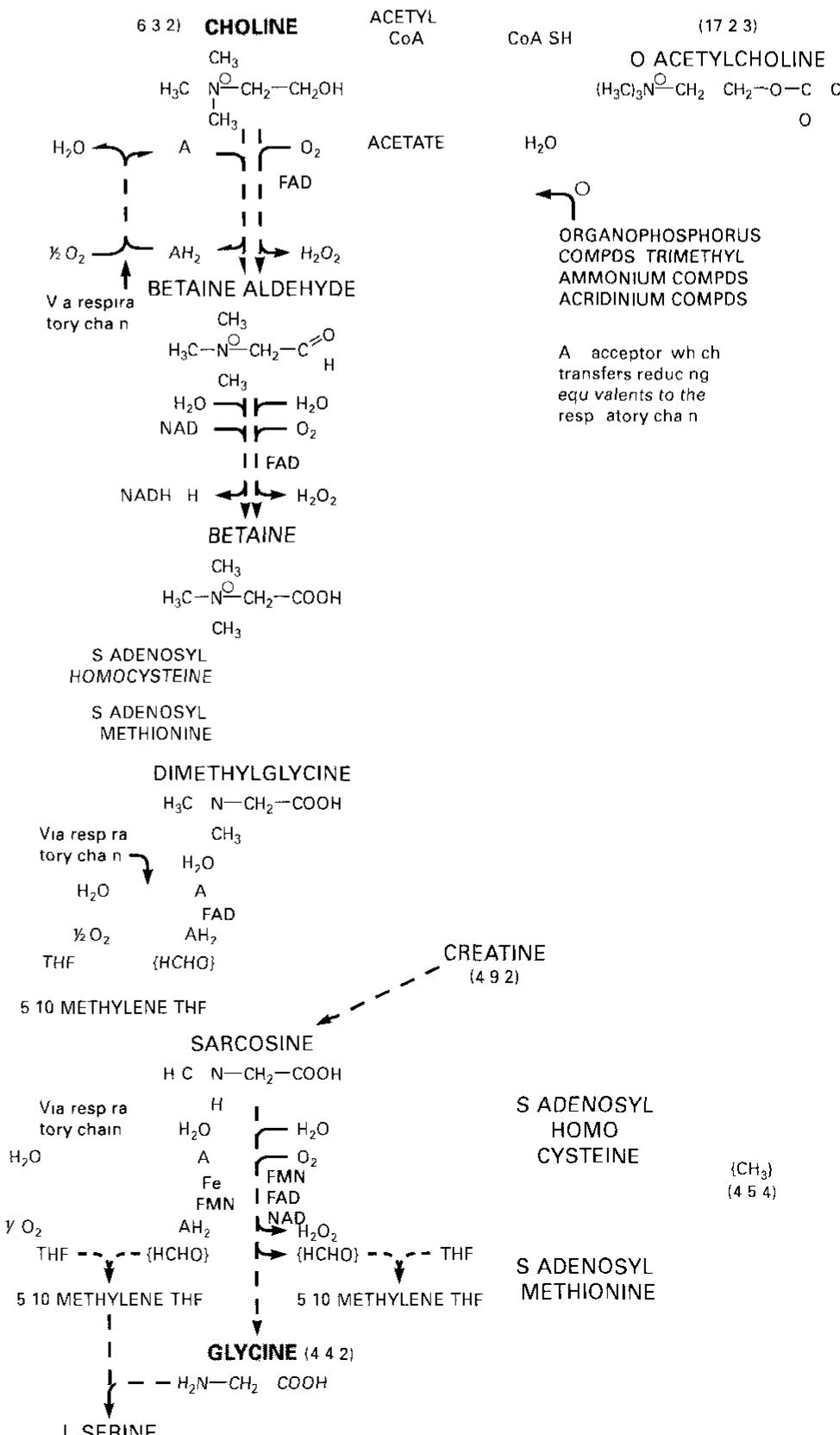

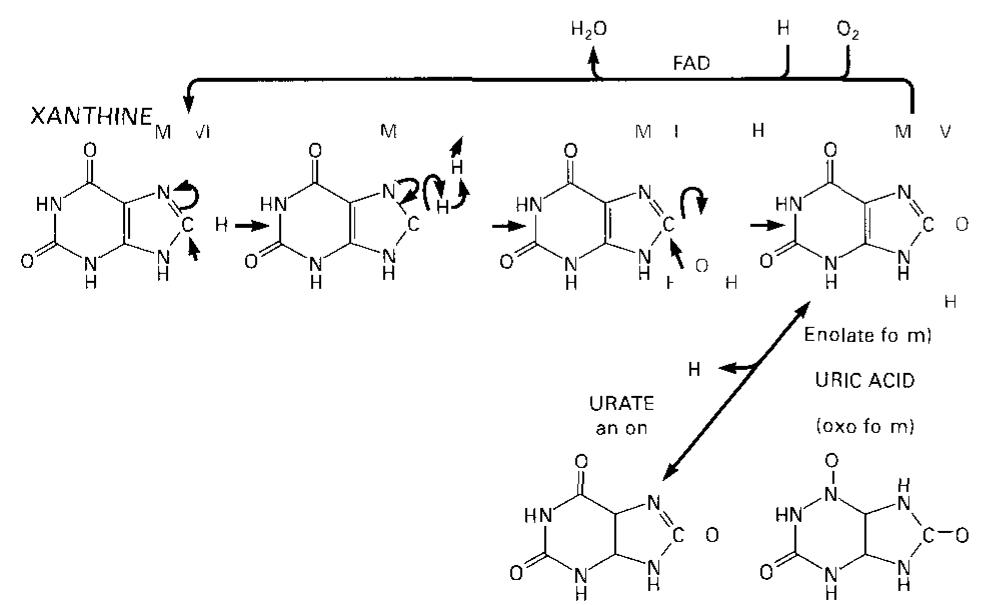

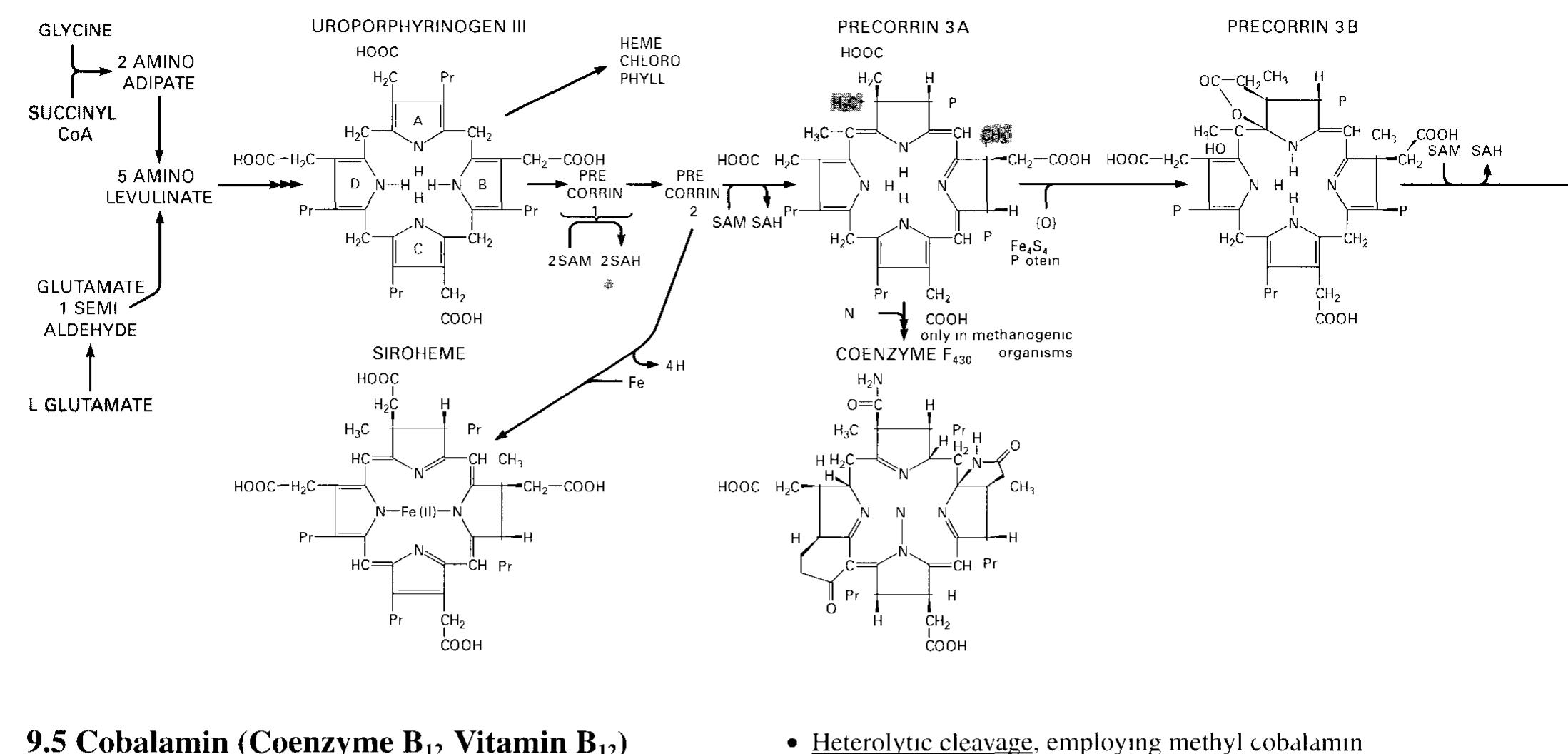

The book "Biochemical Pathways" aims to provide concise and comprehensive information on metabolic pathways, enzymatic reactions, and their regulation, without the extensive historical context typically found in textbooks. It focuses on a variety of biological systems, including bacteria, plants, and animals, presenting knowledge through clear illustrations and tables to facilitate quick understanding. The work is designed for readers looking for a systematic overview of biochemical interrelationships while omitting detailed experimental methods and the complete range of literature references.

Figures (446)

![The energy required tor its formation 1s called activation energy AG* which can be calculated from this equilibrium by applying Eq [1 5 4] as Arrow = shift of the plot when the concentration of the other substrate is raised “igure 1 5-5 Lineweaver-Burk Plots of Two-Substrate Reactions](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_009.jpg)

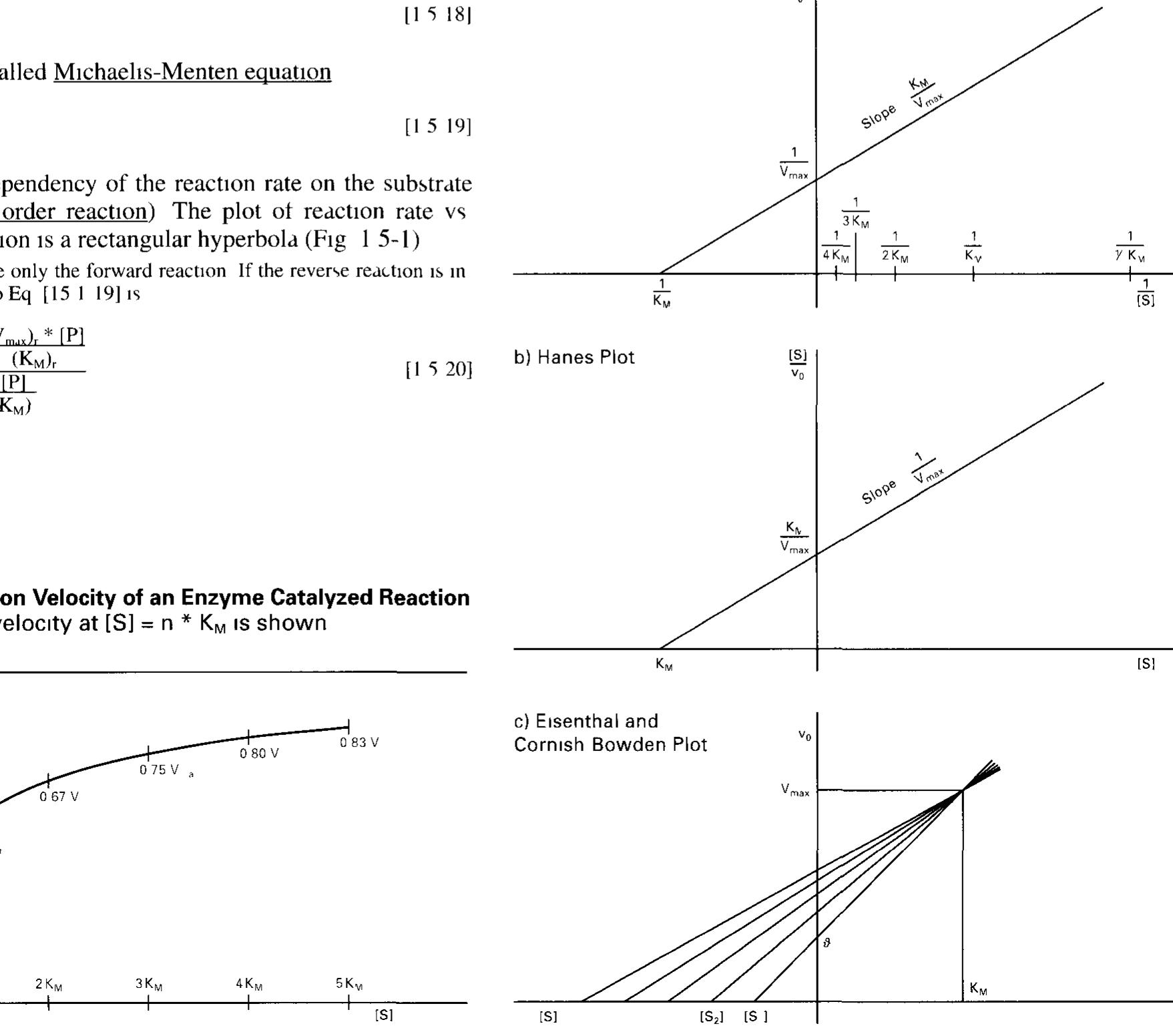

![2.5.2 Regulation of the Activity of Enzymes (For a Mathematical Treatment see 1.5.4) Dannlatian danandinag am onhocteaota Camneantratinn«s TA tha mance? SECACHICIIE SOO 1.0. F) Regulation depending on substrate concentration: In the most simple case, the dependency of the reaction rate on the substrate concentration according to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. [1.5-19], Fig. 1.5-1) 1s a means of controlling the substrate through- put. Zymogen activation: Some enzymes are synthesized as mactive precursors (zymogens or proenzymes) which have to be processed into their active form by limited proteolysis. Examples are diges- tive enzymes such as chymotrypsinogen or trypsinogen (Fig. 2.5-1) They are synthesized in mammalian pancreas as zymogens. After hormone-controlled release into the small intestine they are irre- versibly processed by trypsin or enteropeptidase, respectively, to become active proteases (Fig. 17.1-11).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_022.jpg)

![Using [Mb ] for the total myoglobin concentration [Mb] + |Mb O ] a derivation analogous to the Michaelis Menten equation [Eq 15 19] but without further turnover to products yields](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_087.jpg)

![Figure 6.1-3. Schematic Drawing of the Animal Fatty Acid Synthase Dimer Reaction sequence (Fig. 6.1-4): Specific acy] transferases (one in animals, two in yeast) transfer an acetyl residue from acetyl-CoA to a cysteine-SH of the 3-oxoacyl synthase component (‘peripheral SH group’) @ and a malonyl residue to the ‘central’ SH group of the ACP component of the multienzyme system. Condensation with an acetoacetyl chain (bound to the central SH group) occurs with simultaneous decarboxylation, thereby energetically favoring chain elongation @). This step is irreversible. Then the resulting C, residue is reduced by NADPH at the oxoacyl reductase component ©, dehydrated to a 2,3-desaturated intermediate @ and reduced again by the enoyl reductase ® (also using NADPH as a reduc- tant; NADH in E.coli). The yeast enzyme contains flavin. Finally, the butyryl chain is transferred to the ‘peripheral’ SH group ©. Condensation with another malonyl! residue initiates another round of chain elongation.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_091.jpg)

![Farnesylation takes place if X = serine methionine or glutamine Geranylgerany] 1s attached 1f X = leucine or phenylalanine By Pane EDN ay ar HARES pp eh SMMC DON OSL t ASemmnO RODS BR ce a ee Re is pee Many proteins are attached to cellular membranes by isoprenoid anchors (via a thioether bond to mostly farnesyl, sometimes ge- ranylgeranyl chains), e g Ras (175), G, proteins (17 4) and heme A (521) This prenylation determines the location and the func tron of the proteins The enzymatic reaction 1s shown 1n Fig 7 3-1 IS AUACTIEM TE ZN = IRGC OF POUCH Y taal Proteins of the Rab group which contain -C-C- or C X C-~ sequences ar geranylgeranylated similarly The enzyme 1s assisted by the Rep protein](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_110.jpg)

![ee nnn ee EN I NEI SAE ROE NESE! Only a few regulatory events during the elongation step are known so far The overall RNA chain elongation rate, however, 1s propor tional to the growth rate, ensuring that no excess RNA 1s produced when the translation system operates slowly under conditions of liamited nutritional supply Stringent control: Starvation for an amino acid in bacteria causes a drastic decrease im transcription levels, caused by a signal from the translation step In this stringent contro] mechanism, translat ing ribosomes whose A sites are occupied by non-aminoacylated tRNAs bind the stringent factor enzyme, which then synthesizes the unusual nucleotide guanosine tetraphosphate (PP 5’ G 2’-PP) This compound, 1n turn, reduces transcription of rRNA and tRNA genes (and others) 10- to 20-fold by decreasing the affinity of Pol to the respective promoters via an unresolved mechanism On the other hand, amino acid biosynthesis 1s stimulated](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_162.jpg)

![Figure 11 3-4 Splicing Mechanism for mRNA Besides this mechanism (group III introns) other splicing mechanisms exist They proceed with an external guanosine nucleotide instead of the branching point A (group I rRNA) or with a hgation procedure after endonuclease split ting of the pre mRNA (group [IV tRNA) Splicing of group II introns (e g muito chondria and chloroplast mRNA) resembles the group If] mechanism but with out participation of snRNPs Frequently the group I or I procedures are per tormed by RNA activity only (self splicing e g rRNA in Tetrahymena) Exon ot ditterent RNA strands can also be combined by splicing mechanisms (trans splicing e g MRNA 1n Trypanosoma)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_180.jpg)

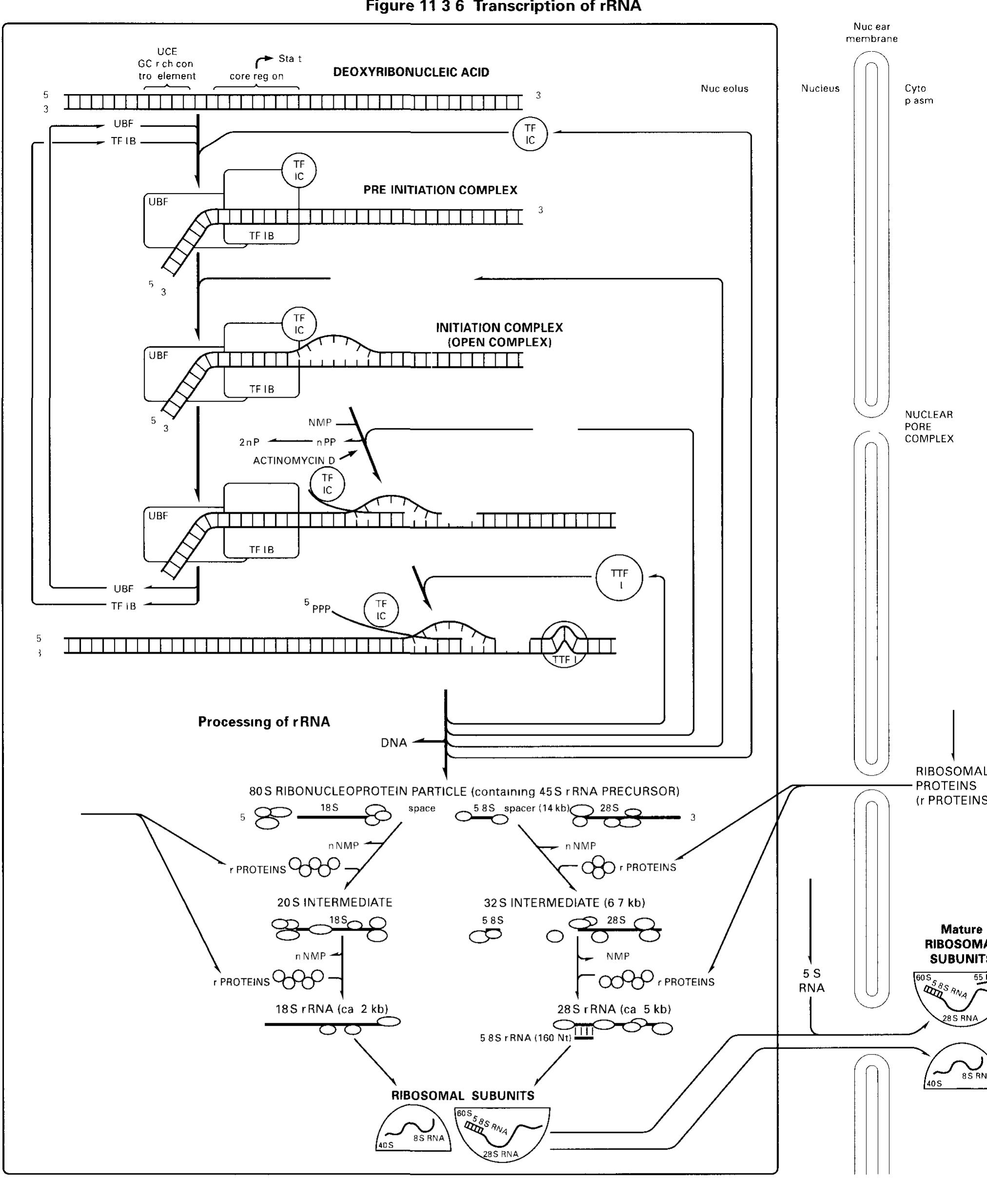

![RNA polymerase I core promoters (Fig. 11.4-3): RNA poly- merase I promoters (and the vast majority of RNA polymerase III] promoters) lack TATA boxes The core promoter (in mammals and amphibians) consists of two critically spaced sequences the upstream control element (UCE, location at -200 -—100 nucleo tides from the start site) and the core region (location at-50 +20 nucleotides therefore enclosing the start site) Only little tran scriptional control 1s exerted on pre-rRNA synthesis](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_190.jpg)

![Infection of the bacterial cell (Figure 12.2-3): Adsorption to the E colt host cell takes place via specific interaction of the phage tai] fiber and a maltose group of the bacterial outer membrane Then the phage DNA 1s injected through the tail into the host cell The linear DNA 1s transformed into a cyclic form, whereupon the host DNA ligase closes the phage genome ring covalently and the DNA gyrase produces supercoiled phage DNA Now the phage enters one of two different states](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_203.jpg)

![The initiation complex for reverse transcription [consisting of the viral enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT), the nucleocapsid pro- teins and the viral primer t-RNA] 1s being activated by the viral](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_207.jpg)

![[pb glucuronate (2 sulfate) (a1— 4) N sulfo b glucosamine (6 sulfate) (&@1— 4)] (mostly) HEPARIN 6* 10> 25*10'Da contains also some D-Gal and b xylose Large quantities are found in mast cells lung and liver Heparin ts an in hibitor of blood coagulation (20 3) by promoting complex forma tion between active proteases (Ila [Xa, Xa) and antithrombin II]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_213.jpg)

![Figure 15.6-2 Redox Potentials E4[mV, 25 °C, pH = 7 0] of Substrate Couples](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/figure_240.jpg)

![Table 17.4-2. Mammalian Gg, Proteins (Tightly Associated Complexes) Membrane anchored_ * by farnesy] at C terminal serine # by geranylgeranyl at C terminal leucine Also known B, B; ¥,(# pairs with B, and 8B, widespread occurrence) y;(# pairs with B and B widespread occurrence) y; (# pairs with B, and B) widespread occurrence) ys # in olfactory epithelium) y , G# pairs with B, and B.) y (* similar to y, pairs with B widespread occurrence)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/39117587/table_085.jpg)

Related papers

Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 1965

Dr. Popov began this half of the lecture by stating that memorizing structures of coenzymes would be unnecessary. We should instead know what they are used for I. The Structure of Coenzyme A [S30]: a. Coenzyme A is involved in the metabolism of fatty acids II. Enzyme-catalyzed transaminationsp [S31] III. Pridoxal phosphate, the prosthetic group of aminotransferases [S32] IV. Pyridoxal phosphate is bound to the enzyme through a Schiff-base linkage[S33] V. Role of biotin in carboxylation reactions [S34] a. Biotin is a water soluble vitamin. b. Biotin is utilized as a prosthetic group of several enzymes. c. The major function of Biotin is to serve as a cofactor for carboxylation reactions. d. Biotin will later be discussed as being associated with pyruvate carboxylase in the Citric Acid Cycle. e. A carboxylation reaction involves the incorporation of CO2 into a biological molecule.

Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry, 32th ed, 2023

Presently entitled Harper’s Biochemistry, the book continues, as originally intended, to provide a concise survey of aspects of biochemistry most relevant to the study of medicine. Various authors have contributed to subsequent editions of this medically oriented biochemistry text, which is now observing its 83rd year.

2021

Advertência Legal / Legal Warning |. Reservados todos os direitos. É proibida a duplicação, total ou parcial desta obra, sob quaisquer formas ou por quaisquer meios (electrónico, mecânico, gravação, fotocopiado, fotográfico ou outros) sem autorização expressa por escrito do editor / All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or as a whole by any process or in any media (electronic, mechanical, recording, copying, photographic or others) is extrictly forbidden without the written authorization of the editor.

Advances in Enzyme Regulation, 1963

THE present paper will mainly describe some metabolic changes in liver after thyroxine treatment as a result of what we believe to be an enzymic induction. Several features distinguish such a process from the immediate or short-term control of metabolic rates which we find in organs under voluntary state of activity. In the latter case, the control of metabolic flow operates in the presence of a constant pattern of enzymes. A short description of this might be helpful however.

Since the discovery of enzymic fermentation by Louis Pasteur, the idea has been widespread in biochemistry that molecular interconversions and interactions in living systems are mediated by enzymes. However, recent advances in sensitivity and separation power of analytical methods has led to isolation and identification of a variety of products that cannot be mapped to specific enzyme-catalyzed biochemical pathways. These products appear in the organism because chemical characteristics of biomolecules are not limited to the needs of living systems realized through enzyme-catalyzed processes. This review provides a summary of such nonenzymic interactions. The following are discussed: I) products of biogenic amine binding to carbonyl-containing compounds in the Pictet-Spengler reaction (endogenous neurotoxins, which impair mitochondrial functions and seem to contribute to development of age-related neurological disorders including parkinsonism); 2) products of Schiff base formation with subsequent Amadori rearrangement (nonenzymic protein glycation involved in age-related diabetes-like disorders and atherosclerosis; 3) prod ucts of Michael addition of methylglyoxal: 4-hydroxynonenal, and other derivatives of nonenzymic conversions of carbohydrates and lipids; 4) products of modification of biomolecules with nitrogen-and oxygen-derived free radicals, which contribute to cancer and aging. Some evolutionary and biomedical implications of nonenzymic parametabolic processes are discussed .

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (50)

- Literature: Apancio, OM et al Cell 91(1997) 59-69

- Campbell, JL J Biol Chem 268(1993)25261-25264

- Diller, J D , Raghuraman, M K Trends in Biochem Sci 19(1994)120-325

- Nasmyth, K Current Opin in Cell Biol 5(1993)166-179

- Roberts, JM Current Opin in Cell Biol 5(1993)201-206

- Roca, J Trends in Biochem Sci 20(1995)156-160

- Sugmo, A Trends in Biochem Sci 20(1995)319-323

- Stillman, B Cell 78 (1994) 725-728

- Toyn, }H,etal Trends in Biochem Sci 20(1995)70-73

- Umar, A , Kunkel, T A Eur J Biochem 238 (1996) 297-307 (various authors) Science 247 (1996) 1643-1677

- Waga, S , Stillman, B Nature 369 (1994) 207-212

- Wang, TA,Li,J J Current Opin in Cell Biol 7(1995)414-420

- Wang, TSF Ann Rev of Biochem 60(1991)513-552

- Wang, JC Ann Rev of Biochem 65(1996)635-692 Literature: Aso.T., etal.. FASEB J. 9 (1995) 1419-1428.

- Berget, S.M.: J. Biol. Chem. 270 (1995) 2411-2414.

- Dahmus, M.E.: Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1261 (1995) 171-182.

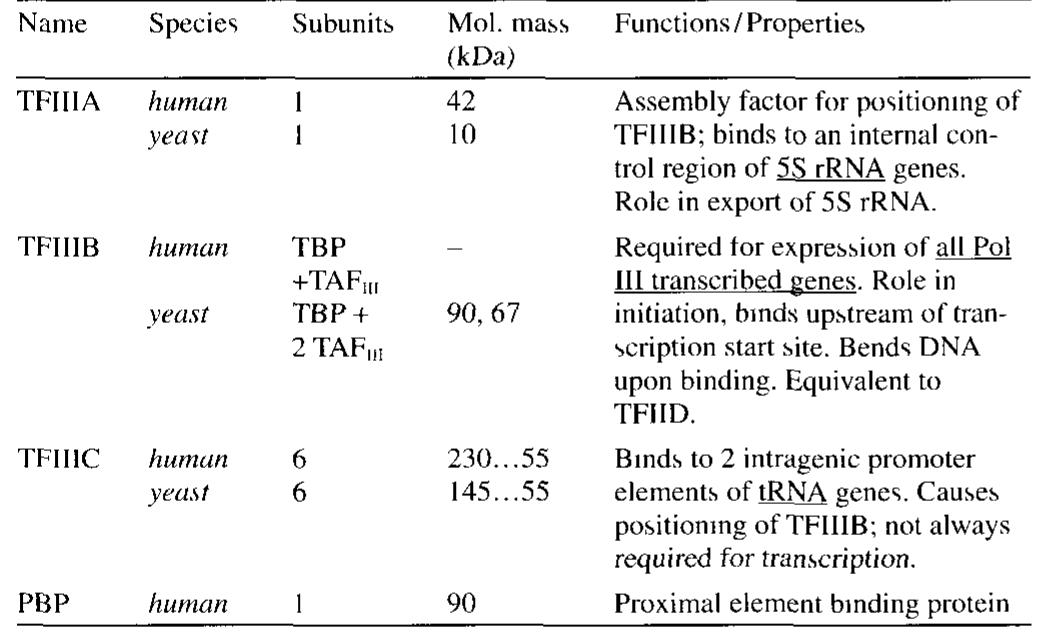

- Geiduschek, E.P., etal.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 7 (1995) 334-351.

- Koleske, A.J., Young, R.A.: Trends in Biochem. Science 20 (1995) 113-116.

- Kramer, A.: Ann. Rev. of Biochem. 65 (1996) 367-409.

- Maldonado, E., Reinberg, D.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 7 (1995) 352-361.

- Melere, T., Xue, Z.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 7 (1995) 319-324.

- Mornssey, J.P., Tollervey, D.: Trends in Biochem. Sci. 20 (1995) 78-82.

- Newman, A.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 6 (1994) 360-367.

- Pugh, B.F.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 8 (1996) 303-311.

- Scheer, U., Weisenberger. D.: Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 6 (1994) 354-359.

- Sharp, P.A.: Cell 77 (1994) 805-815. (various authors): Trends in Biochem. Science 21 (1996) 320-364.

- Wahle, E.: Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1261 (1995) 183-194.

- Zavel, L., Reinberg, D.: Ann. Rev. of Biochem. 64 (1995) 533-561

- I. UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine-lysosomal enzyine N-acetylglucosaminephospho- transfcrasc (2.7.8.17)

- Mannosyl-oligosacchande 1,2-a-mannosidase (mannosidase I, 3.2.1.1 13)

- Mannosyl-glycoprotein (3-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltranslerase (N-acetylglucos- aminyltransfcrase I, 2.4.1.101)

- Mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,3-1,6-a-mannosidase (mannosidase II, 3.2.1.1 14)

- 3-1,4-Mannosyl-glyeoprotein [3-1,4-N-acctylglucosaminyllransf erase (N-acetyl- glucosamine translerase III, 2.4.1.144)

- Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl translerase (2 4.1.41)

- Acel^lgalactosannnyl-O-gly cosy I -glycoprotein [3-1.3-N-acetylglucosaminyl- Iranslerase (2.4.1.147)

- Glycoprotein-N-acetylgalaetosamine 3-(3-galactosyllransferase (2.4.1.122)

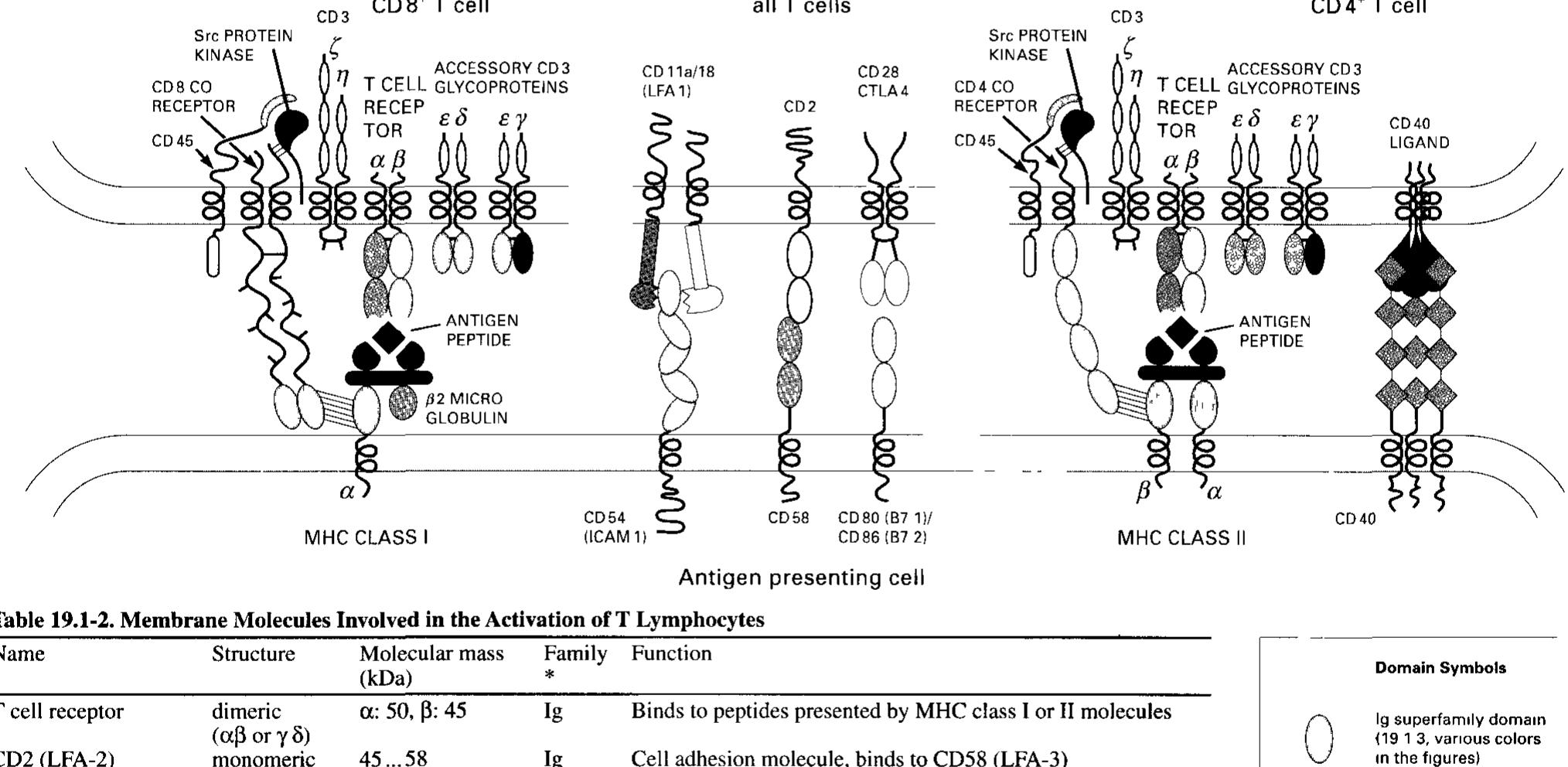

- Abbas, A.K. etal.: Cellular and Molecular Immunology. W.B. Saunders Co. (1991).

- Brown, E. et al: Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6 (1994) 43-145.

- Callard, R.E., Gearing, A.J.H.: The Cytokine Facts Book. Academic Press (1994).

- Germain, R.N.: Cell 76 (1994) 287-299.

- Ikuta, K. etal: Ann. Rev. Immunol. 10 (1992) 759-783.

- Honjo, T., Alt, F.W. (Eds.): Immunoglobln Genes, 2nd ed. Academic Press (1995).

- Janeway, C.A. jr., Travers, P.: Immunobiology. 2nd ed. Current Biology and Garland Publishing Inc. (1997).

- Janeway, C.A. jr., Bottomly, K.: Cell 76 (1994) 275-285.

- Kishimoto.T. etal: Cell 76 (1994) 253-262.

- Lichtenstein, L.M.: Scientific American 269 (1993) 117-124.

- Schlossman, S.F. et al. (Eds.): Leucocyte Typing V. Oxford University Press (1995).

- Paul, W.E.: Fundamental Immunology. 3rd ed. Raven Press (1993).

- Rammensee, H.G., Monaco, J.: Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6 (1994) 1-71.

- Reth, M.: Ann. Rev. Immunol. 10 (1992) 97-121.

Related papers

Microbial Biotechnology, 2008

Archives of Organic and Inorganic Chemical Sciences, 2018

Annals of The New York Academy of Sciences, 1987

Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 1988

Regulation and Adaptation, 2004

Reactome - a curated knowledgebase of biological pathways

Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2016

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 2007

andrey khorst

andrey khorst