Malfunctioning During Service Life

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

International Fracture Mechanics Summer Schools have been held from 1980 and have attracted a large number of well-known specialists and participants. Monographs published after every school have been the most effective references in fracture mechanics application for scientists and engineers in former Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro. Previous schools have covered: 1. Introduction to Fracture Mechanics and Fracture-Safe Design (1980) 2. Modern Aspects of Design and Construction of Pressure Vessels and Penstocks (1982) 3. Fracture Mechanics of Weldments (1984) 4. Prospective of Fracture Mechanics Development and Application (1986) 5. The Application of Fracture Mechanics to Life Estimation of Power Plant Components (1989) 6.

Figures (408)

![development of Inglis [4]. Figure 3 shows the results of Griffith’s series of experiments on glass fibres having different thickness. As the fibre thickness decreased, the breaking stress (load per unit area) increased. At the limit of large thickness, the strength is that of bulk glass. But of considerable interest is that the theoretical strength is approached at the opposite limit of vanishingly small thickness. This observation led Griffith to suppose that the apparent thickness effect was actually a crack size a. Figure 4 illustrates his observation. It is worth mentioning here that this “size effect” is responsible for the usefulness of materials like glass and graphite in fibre composites; that is, the inherent defects can be considerably reduced by using such materials in fibre form bound together by a resin. The basic idea in the Griffith fracture theory is that there is a driving force for crack extension (that results from the release of potential energy in the body) along with an inherent resistance to crack growth. The resistance to crack growth, in glass at least, is associated with the necessity to supply surface energy for the newly formed crack surfaces. Griffith was able to formulate an energy balance approach according to [3]. This has led to a critical condition for fracture that can be written as an equality between the change in potential energy due to an increment of crack growth and the resistance to this growth. For an elastic-brittle material like glass, this is](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_003.jpg)

![Figure 5. Pseudo-atomic model for fracture mechanics calculations Fracture by rupture of the interatomic bonds can help to understand fracture toughness origins. Implicit in fracture analyses is the idea that atomic bonds must be ruptured to allow a crack to propagate (Fig. 4). The first quantitative treatment considered interatomic bond rupture, Elliott [12]. Using the linear elastic (continuum!) solution for a cracked body under uniform tension, Elliott evaluated the normal stress and displacement values along a line parallel to the crack plane (Fig. 5), but situated at a small distance b/2 into the body. He then plotted the stress at each position as a function of the displacement at that point. The shape of this function turns out to be consistent with interatomic force separation that obeys Hooke’s law for small separations, exhibits a maximum, and approaches to zero at large separations, Eq. (1). On the basis of this finding, Elliott formulated a model of two semi-infinite blocks that attract each other with interatomic forces, Fig. 5.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_005.jpg)

![Figure 8. a. The Dugdale model b. Dugdale’s results for the plastic zone size and compared with analysis which 1s an a W available, an was provided closed-form complex variable theory sed tha ying a suppo band hile elastic-plastic pproximate explicit rela in a key pa solution ap analyses to de plicable for p of elasticity, d for a thin s heet, loaded in ion was needed per published in 1960 by Dugdale [22] in which he developed a post-yield fracture criterion and the basis for the COD method. ermine the plastic region at a crack tip were for din order to advance the COD concept. This ane stress conditions. Using methods of the eveloped by Muskhelishvili [23], Dugdale [22] ension, the yielding will be confined to a narrow ong the crack line. Mathematically, this idea is identical to placing internal stresses on the portions of the (mathema being the remaining stress-free length. ical) crack faces near its tips; the physical crack The magnitude of the internal stresses in Dugdale's model are taken to be equal to the yield stress of the material. In order to determine the length over which they act, Dugdale postulated that the stress singularity must be abolished. For a crack of length 2a in an infinite medium under uniform tension o. led Dugdale to the relation](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_008.jpg)

![cence cceeeee nee ee eee en ener eee eee ee en eS ee eee In order to determine the degradation of material, which is formed from components with different CTE, the basic problem, shown in Fig. 6, should be solved. The aggregate with the CTE @ is embedded in the hardened cement paste with the CTE q. For simpli- city, it will be assumed that Young’s modules of two materials are equal, E, = E,= E. Only the case of the plane stress will be considered. Due to temperature increase 0= T- To, the stress in both aggregate and cement paste would occur, because of the mismatch of the CTE, a, < @. This phenomenon is referred to as TICC (Venecanin [14]). The way how to determine the stresses in the aggregate and cement paste can be found in papers: Sumarac [15], and Sumarac, Krasulja [16]. Within the aggregate the stresses are constant,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_022.jpg)

![Figure 7. Comparison of theoretical and experimental results 2.3. Plane sheet weakened by elliptical void Consider the problem of the elliptic cylinder (a3 —> ») (Fig. 8.) embedded in the elastic isotropic material with the same elastic parameters EF (Young’s modulus) and v(Poisson’s ratio). Eshelby, in his 1957 paper [19], referred to “eigenstrains” as stress-free transfor- mation strains. He proved that the uniform “eigenstrain” a within the elliptical inclusion, cause the uniform “eigenstresses” Oj” in the same region (see also Mura [20]): “ & where yis the density of concrete (kg/m’), fis resonant frequency (Hz), and / the length of specimen (m). Resonant frequency data were obtained by CNS-electronics “ERUDITE” equipment. Results for dynamic modulus of elasticity, obtained from expression (61) and from measured data, are presented in Fig. 7. Usually, it was assumed that concrete with the river aggregate would be more resistant to temperature increase, and the concrete with limestone aggregate could have exhibited changes caused by the TICC effect. In Fig. 7, temperature exposure has a quite perceptible influence on both concretes. The decrease in dynamic modulus of elasticity was recorded for both concretes. From Fig. 7 one can notice that concrete made with river aggregate showed a slightly slower degradation rate. At the end of thermal treatment (160°C), the value of E decreased for concrete with RA for 25.4%, while for concrete with CL for 27.2%. Such drop of basic mechanical and deformational properties is somewhat surprising, since temperatures below 160°C are not considered high for concrete. a Ee et ee ee Le es: A ee ad ee, a Se a een](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_023.jpg)

![Figure 3. Short fatigue crack in high-strength spring steel under fully reversed torsion (Akid and Murtaza) [11]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_032.jpg)

![The critical local crack tip loading for dislocation emission can be expressed as a criti- cal energy release rate at which stable equilibrium of dislocation loop becomes unstable For the simplified geometry adopted in Fig. 9, the dislocation loop shape is describec only by a semicircle of radius 7. In this case, the condition for spontaneous dislocatior emission is obtained by, first, minimizing the total energy of the cracked body witl respect to r, and next, finding the condition where the second order derivative of energy changes from positive to negative, Rice [21].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_052.jpg)

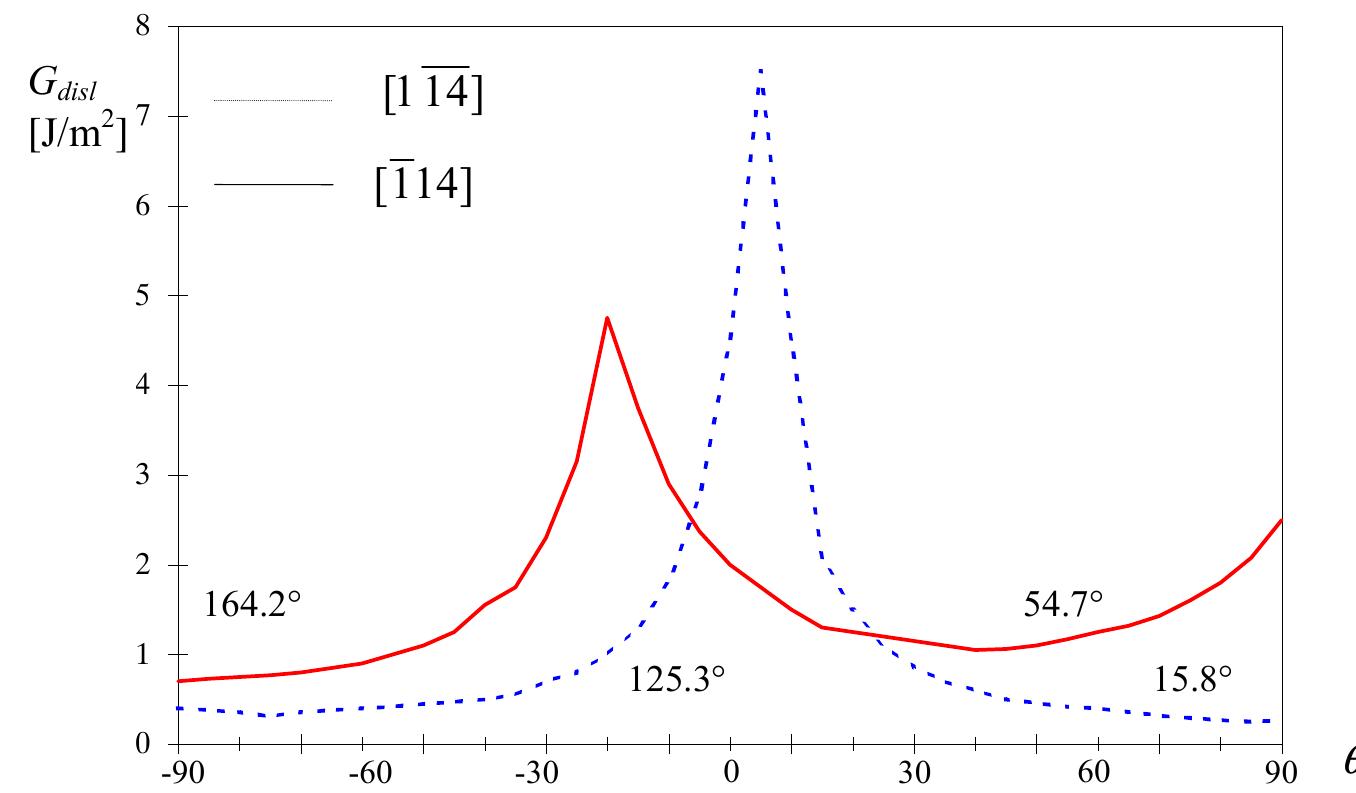

bicrystals. For Cu [110] symmetrica along the ti b=ai112)/6 Burgers vec rate for dislocation emission However, the partial disloca stacking fau ly tilted bicrystals (Wang [18]), where the crack front lies t axis, the likely dislocations to be activated are partial dislocations with and @= 60° and or is perpendicu t cracked. Upon @= 0°. The partial dislocations with @= 0°, such that the ar to the crack front, have a lower value of energy release then those with @= 60° and are favoured to pop out first. ion with @= 0° reaches the stable equilibrium due to the nucleation of partial dislocation with @= 60°, the stacking fault is removed and the dislocation pair expands unstably from the crack tip.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_053.jpg)

![Figure 12. A schematic illustration of the crystallographic configurations in the Fe-2,7% Si %5[100]/(021) EE EEE EIDE EE III IIE EEE EI II IIE IEEE ge IES FT EI For [100] symmetrically tilted Fe bicrystals the likely dislocations to be active from the crack tip lying along [100] might be those with b = a(111)/2 and @= 35.26° on {110} plane, Wang and Mesarovic [20]. The critical Gzj;; versus @ curve predicted by the Rice- Thomson type model is presented in Fig. 13. Here the core cut-off is r, = 2/3b (dashec line) or 7, = 1.0455 (solid line), the ledge energy is Yeage = 0.4% and an isotropic elasticity 18 Nreci1med,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_055.jpg)

![the (111) system are favorable for nucleation, so that @= 125.3°. From Eq. (57), energy release rate for positive [114] direction is Goi, = 0.86 J/m*. For (221 Jeu interface and negative [ 111) sli brittle in [114] crack direction, the active s pinSE angle y’=—79°, the system (111) are : (43), energy release rate for negative [ 114] direction is Gas) = 4.9 Jim’. ip systems have changed the (111 ) to the p plane with @= 54.7° and @= 164.2°, respectively. Due to the large negative Figs. 10 and 15 it may be conclud favourable for nucleation, so that @= 164.2°. ed that the cracking of copper bicrystals is a negative direction, while in Cu/sapphire bimaterials, cracking behaviour is he negative direction. As in bicrys als, Gas; is a function of @ but due to mode II loading conditions that are the most in the bimaterials, the minimum value occurs at arge values of @ angle, @= 130°. The minimum value of Gs; for bimaterials is much ower then for bicrystals. The phase angle effect plays an important role in bimaterial systems. The phase angle offect is shown in Fig. 16, which gives Gai; versus w’ for various slip plane inclination angles. Solid lines correspond to angles associated with direction [1 14 ] and dashed lines correspond to angles associated with direction [114]. Comparison of curves at y’= 0° and y’= 79° shows that favoured directions for dislocation emission reverse when the phase angle is altered. Crack tip fields for the crack along the interface between elastically dissimilar solids](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_058.jpg)

![The first and the oldest type of steel used as structural steels are plain carbon steels. The increase in strength was based on increase in carbon content. Carbon in Fe is a solid solution, with limited solubility. During deformation, as a result of applied stress, disloca- tions through their movement interact with obstacles, what in turn requires increase of applied strength for further deformation. Influence of carbon content on transition temperature in carhon cteele ig chown in Fico 2 [45].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_067.jpg)

![Figure 3. Influence of sulphur content on transition temperature in steels [2]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_068.jpg)

![ins as Manganese is substitutionally soluted in Fe, but the effect on strengthening is not pro- nounced since it depends on differences in atomic size. Mn and Fe are neighbouring elements in the periodic table. In structural steels, the content of Mn is in most cases limited to 1.5—1.7%, while larger content leads to increase of A,3 temperature and nuclea- tion of pro-eutectoid ferrite [6]. In other steels, the Mn content may be as high as 12%. The influence of Mn on transition temperature in C-Mn steels is shown in Fig. 4, [7]. Increase of Mn content decreases transition temperature to very low temperatures. The main mechanism lies in the sulphur have strong chemical affinity, leading to s during solidification of steel. solution is the addition of suf! formation of MnS The simplest way and tempered steels. During further metal working, MnS inc ed (rolling) or fractured and d ispersed (forging). Presence of sions in as-rolled steels is very dangerous, since the edges be manganese-sulphide). Manganese and pontaneous formation of MnS inclusion o completely remove S from the solid ficient amounts of Mn. This ro rise in toughness in low carbon steels, with excep e of Mn ensured significant ions in some medium carbon quenched usions can become elongat- long elongated MnS inclu- have as stress concentrators, leading to fracture or to lamellar tearing in welded constructions. The next task was to eliminate sulphides as critical particles. The solution was add itionally alloyed with Ca or rare earth elements (RE). This improvement was directly based on knowledge provided by fracture mechanics, i.e. addition of Ca primarily influences the shape of MnS. This feature is shown in Fig. 5 [1].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_069.jpg)

![Figure 5. Shape of MnS after rolling (RD-rolling direction): (a) no Ca added; (b) addition of Ca [1] The next problem steel producers faced was the presence of free oxygen, originating from air blowing in converter, or in furnace. In order to eliminate oxygen it was necessary o modify the chemical composition by adding a specific chemical element with strong iffinity to oxygen. The answer came from the diagram of stability of oxides. Usually, Si or Al were used in an amount, estimated from the last chemical composition analysis Juring steel production (ladle after converter). This procedure introduced a new type of steels, so called killed steels, since oxide formation prevents bubbling of liquid metal. Furthermore, addition of Al became more interesting due to some observations showing hat in some Al-killed steels at grain boundaries precipitation of AIN occurred, decreasing srain boundary mobility. This was observed in steels in which Al was added in high amount; air-blowing (instead of oxygen, nowadays) led to reasonable presence of nitro- sen and strong affinity between Al and N. This was the first empirical case of grain ooundary control, but significant industrial application did not follow. On one hand, ohysical metallurgy defined mechanisms of deformation strengthening and recrystalliza- ion, and on the other hand, it has been a great effort to choose elements from the periodic able that behave similarly to Al, but with much better control. At firet an the lahnaratary ceale and later an fill indiuectrial ecale camnletely new Figure 5. Shape of MnS after rolling (RD-rolling direction): (a) no Ca added; (b) addition of Ca [1] After rolling, MnS becomes elongated, with very sharp tip. This shape leads to beha- fiour close to stress concentration. On the other hand, in Ca-treated steels, during solidifi- ‘ation, MnS starts to grow spherically. During both hot and cold deformation, due to 1igher Young’s modulus, Ca treated particles remain spherical. This approach has been -ver since of great practical importance, since it has focused attention on particle shape nstead on the overall level of impurities. Therefore, since spherical second-phase yarticles are not critical for stress concentration, toughness is improved, without any nfluences on other mechanical properties. In modern structural steels, sulphur content is ‘lose to 0.0050%.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_070.jpg)

![Figure 6. Chronological development of the use of microalloying (MA) elements in steels [8] The main motives for developing MA steels were: significant increase in strength, resulting in either lowered construction weight or increased carrying capacity; thermo- mechanical treatment, a demand on the world market for steels with good weldability for pipelines, for which was not possible to use the “traditional” way to increase strength and toughness by heavier alloying- and carbon content. The microstructure of MA steels after hot working is typically fine-grained and consists of small and homogenous ferrite (@) orains. Small amount of cementite is also present (low pearlite steels are also used), together with fine dispersed carbonitride particles that can be observed only on electron microscope. The influences of niobium content and grain size on transition temperature in microalloyed steels are shown in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. Theoretically the hest cqgmbination of strenoth and tonohness is ohtained in fine orain-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_071.jpg)

![Figure 7. Influence of niobium content on transition temperature in steels [9] Figure 8. Influence of grain size on transition temperature [10]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_073.jpg)

![Figure 11. Schematic interrelationship between the yield strength and the transition temperature T>7 for different steels [14]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_076.jpg)

![T he results in Fig. 2 [2] show a large variation in toughness for experiments carrie out with an aluminium alloy (7075-T6) of different specimen thickness. Three regions i the toughness curve: A, B, and C can be recognized, taking into account the fractu profi tures es and stress-displacement curves form obtained in each region (Fig. 2b). The fra are Classified as “slant” or “square”, depending on whether the macroscopic fractui surface is at 45° to the tensile axis or normal to it. The second curve in Fig. 2a indicat how he proportion of square fracture varies with specimen thickness: up to the maximu! of the toughness curve (region A) fractures are completely slant, in thick specimens (regic C) they are generally square, and for intermediate thickness, they are of ‘““mixed-mode’’.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_081.jpg)

![Table 1. Typical values of modulus of elasticity at different temperatures The slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve is the modulus of elasti- city, or the Young’s modulus. The modulus of elasticity is a measure of stiffness of the material, for computing deflections of beams and other members. However, an increase ir temperature decreases the modulus of elasticity. Typical values at different temperatures are given in Table 1, [3].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/table_002.jpg)

![Table 2. Values for n and K for metals at room temperature [4] 2. IMPACT TESTING](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/table_003.jpg)

![The significance of impact testing is illustrated by test results for two high strength steels presented in Fig. 15. Chemical composition is given in Table 3, and tensile proper- ‘ies in Table 4. The difference in strength and ductility is not expressed in the same level as the case with impact toughness properties. Steel A, with low carbon content, exhibited high impact energy at low temperatures (down to —100°C) for crack propagation and also crack initation [8]. However, there is a significant effect of rolling direction. For steel B, with 0.3% C, the impact energy is low, and nil ductility transition temperature can be determined (between —40°C and —60°C).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_120.jpg)

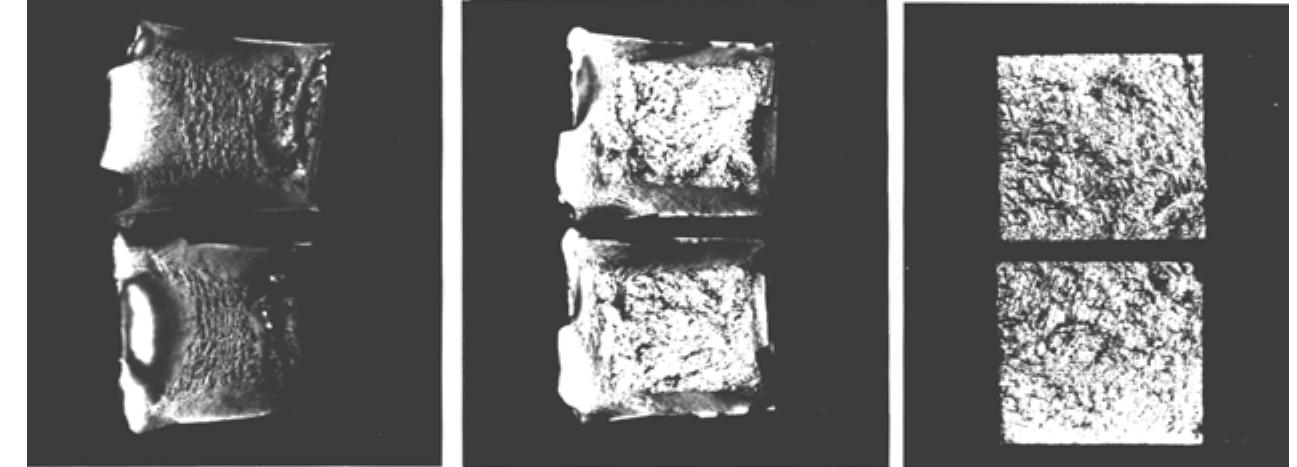

![Figure 18. Explosion bulge test, developed in the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) In addition to fast fracture by explosion shot, a unique “crack-starter” can contribute to brittle fracture condition. In the first development [10] of explosion bulge tests the test plate was supplied with brittle weld bead deposited on the surface of 25 mm steel plate, sized 500x500 mm. The latter feature is a short bead of very hard brittle weld metal which is notched in a manner to insure the initiation of a cleavage crack as soon as the base metal is subjected to any bending. The specimen, with the welded short bead face down is placed upon the circular supporting die and a standardized charge of explosive is detonated at the fixed position above the specimen. During the extremely rapid loading, he brittle weld bead introduces small natural cracks in the test plate (similar to a crack in weld), initiating cleavage cracks at the root of the notch and transferring them to the base metal as running cracks. The behaviour of the test plate depends upon the ability of the base metal to arrest the running crack and to deform while permitting only high-energy absorbing, shear-type fracture to propagate. If the steel is not capable of arresting the running crack, the plate develops many cleavage fractures and breaks flat; that is, little plastic forming occurs downward into the die cavity. Tests can be carried out over a range of temperatures and then the appearance of the fracture determines the transition tempera- tures (Fig. 19). Below the NDT the fracture is a flat (elastic) fracture running completely to the edges of the test plate. Above the nil ductility temperature a plastic bulge forms in the center of the plate, but the fracture is still a flat elastic fracture out to the plate edge. At a still higher temperature the fracture does not propagate outside of the bulged region. The temperature at which elastic fracture no longer propagates to the edge of the plate is called the fracture transition elastic (FTE). The FTE marks the highest temperature of fracture propagation by purely elastic stresses. At yet higher temperature the extensive plasticity results in a helmet-type bulge. The temperature above which this fully ductile tearing occurs is the fracture transition plastic (FTP).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_123.jpg)

![Figure 28. Fracture-analysis diagram showing influence of various initial flaw sizes [13] C- f+ & Data obtained from the DWT and other large-scale fracture tests have been assembl by Pellini and co-workers [13] into a useful design procedure called the fracture analys diagram (FAD). The NDT as determined by the DWT provides a key data point to ste onstruction of the fracture analysis diagram and transition temperature features of stee (Fig. 28). For mild steel below NDT the CAT curve is flat. A stress level in excess of : to 55 MPa causes brittle fracture, regardless of the size of the initial flaw. Extensi Sorrelation between NDT and Robertson CAT tests for a variety of structural steels hav shown that the CAT curve bears a fixed relationship to the NDT temperature. Thus, tl NDT -—1°C provides a conservative estimate of the CAT curve at stress of 6,/ NDT +15°C provides an estimate of the CAT at o= 0, and, the FTE and NDT +50° provides an estimate of the FTP. So, once NDT for structural steels is determined, tl entire scope of the CAT curve can be established well enough for engineering design.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_132.jpg)

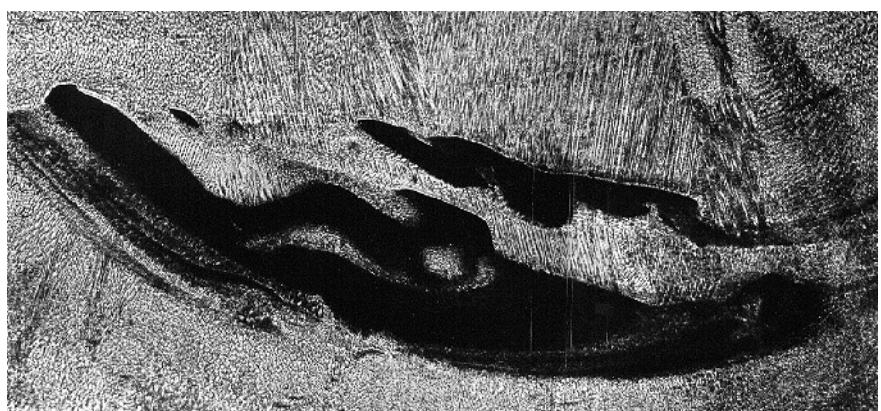

![ee eae Me, ee! ae ee eee, San Loe ir meena Meee a The most common forms of material failures are fracture, corrosion, wear, and defor- mation. Before the actual failure mode can be determined, however, a failure analysis must be performed. In order to analyse a failure, circumstance analysis is required follow- ed by chemical analysis, mechanical properties and microstructural analysis. Fractogra- phic analysis, Fig. 1, often has the most dominant role in analysis of failure of metal parts and constructions, [1]. me: a ~~ - € we Uté<‘<‘ we x om: » » se](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_135.jpg)

![During welded joint testing, a vast number of macroscopic cracks had been detected. The first step was to take samples with the cracked material, positioned in liquid and gas phases of the sphere. In the next step, the small “boat” type specimens from meridian and equatorial welds were prepared, Fig 3. The crack, several centimetres long, was discover- ed in the equatorial weld, propagating in the heat affected zone, Fig. 4. Fractographic analysis was difficult due to corrosion of the fractured surface, and it was impossible to make reliable conclusions about the cause of failure. 3.1. Fracture analysis of the heat-affected-zone For better and easier examination of the cause of welded joint failure, simulated welc ing on the same steel was performed. The microstructure of different temperature region in HAZ had been simulated on the Smitweld LS1402 device. The samples, 60 mm lon; 11 mm wide, and 11 mm thick, had been exposed to different temperatures: 1350°C -orresponding to coarse grain formation; 1100°C — fine grain formation; 950°C — fin srain region above A,3 tempera ransformation of austenite, be 800°C to 500°C of 15s was co esting was performed with C Jepth. The fractured surface of Charpy specimens was analysed by scanning electro microscopy, JEOL35, [2]. Regions corresponding to d ure — austenite-ferrite transformation; and 850°C — par harpy specimens (10x10x55 mm) with a 2mm V no tween temperatures A,; and A,3. The cooling time fror nstant, selected as typical for tested steel welding. Impac ifferent simulation temperatures are shown in a welde le Cc](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_137.jpg)

![Figure 17. Creep curves for 2 4 Cr1Mo steel JODE-UINEe Values diG UsUdlly Ddsed OL UNCdr CAUAaPOAUOT OL CAPCTUMCHtal SHOTT- tune] data. The experience with old power plants showed however, that the deterministic life evaluation, applying the worst case assumption, pile-up conservative assumptions leading to the pessimistic assessment, different to the actual situation and shortening the life time. Typical creep results (Fig. 17) show that between allowable, minimal and mean values, significant life capacity exists compared to the design life, which is reached first. Although a large amount of reserve exists, in the particular case there are no quantitative data, and starting from the worst case assumption it will not be possible to use these capacities. Obviously, the solution of this problem, without negative effects on general safety and reliability of the equipment, is only possible using special methods to measure actual life consumption and remaining life capacity of parts in service and ruling out the corresponding random effect in this respect. Accordingly, from the design life calculation point of view, here is not a matter of correcting the errors in calculation and all strives of “Improvement” in this respect will not be successful. However, the modern method of life design certainly considers the corresponding experiences with the introduction of life monitoring and equipment inspection, contributing in this way to the overall efficiency and reliability of equipment. Programmes for monitoring and life extension are now usual in power plants. The goal of these programmes is the increase of availability, efficiency and reliability of existing power plants by reassessing their structural integrity and the es wesenenentcere aul cto. eeeael coveresreeeniewss | aaciererees](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_165.jpg)

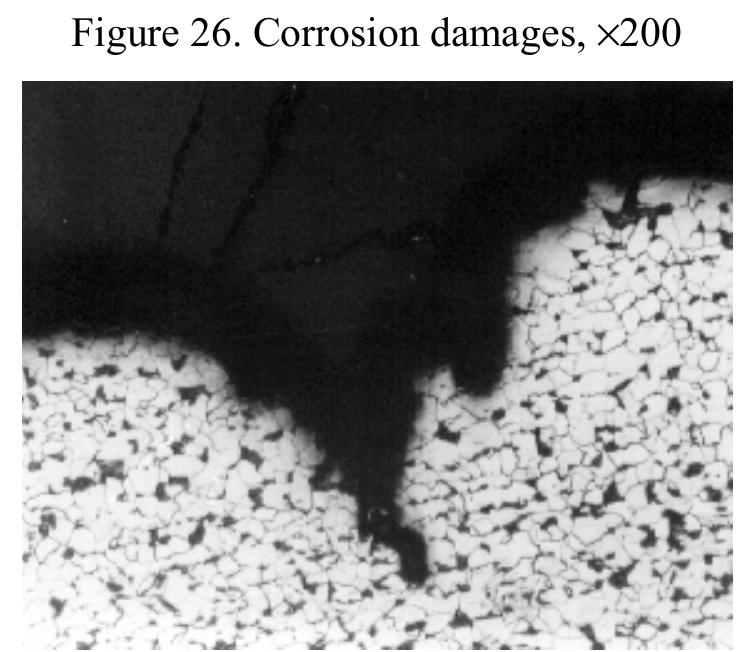

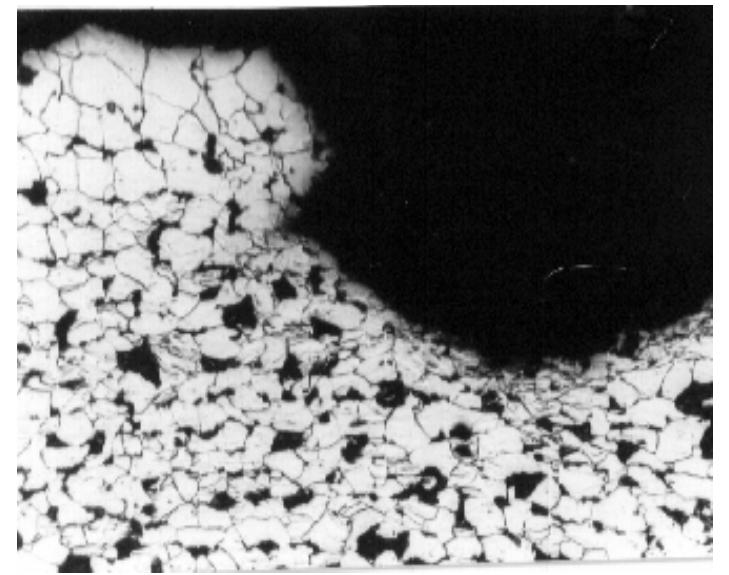

![Te eee eee eee eater eee eer eee ee eee ee eee ee DE eee neon ae ee ee ee a The specimens for experimental investigation were cut from turbine blades, stator and rotors, Figs. 2-4, made of high-content chromium steel X22CrMoV121 (according t DIN standards), which fractured after less then half the predicted life time. These steel belong to the martensitic steel type, with 5% of maximal allowed 6-ferrite content anc which are highly used for turbine blades. The comprehensive experimental investigatiot of microstructure and fracture features 32 different specimens tested by optical micro scopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive analyzer, all performed 11 the aim of determining microstructural variations, and their possible influence on fracture corrosion, and oxidation resistance of blades [13-15]. The basic microstructure of tested steels is martensite with carbides, separated in grai boundaries and within the grains, Figs. 5—6. In addition, an appearance of an extremel large amount of ferrite is detected. The various microstructural flaws already mentione are presented on SEM micrographs: the striped carbides distribution; the inhomogeneou distribution of chromium and the related inhomogeneous distribution of carbides i different zones; very large carbides of chromium, separated in grain boundaries wit decohesion in the particle—matrix interface; very long MnS inclusions passing throug several grains; massive silicon inclusions are also revealed. A relatively large number specimens have a martensitic—ferritic or pure ferritic structure with large chromiut carbides in grain boundaries instead of the necessary structure of tempered martensit Delaminations of microstructure are observed too, Figs. 7-12. As illustrated on the last four figures, the corrosion pits, because of the complex stres](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_171.jpg)

![Figure 1. F asa function of temperature T, for a carbon steel (1) and an austenitic steel (2) Clearly, for materials prone to embrittlement, one can expect still further decrease in fatigue crack size limits in view of such factors as hydrogenation, radiation, and corrosive effects. At the same time, in the case of austenitic steels and aluminium alloys, which do not embrittle at low temperature [1], the area occupied by a fatigue crack prior to fracture scarcely decreases with lowering temperature. A study of fracture of various engineering components and structures has revealed that in most cases their fracture is due to material fatigue, which is known to be responsible for initiation and propagation of fatigue cracks in cyclic loading and such cracks ultimate- ly lead to complete failure of a component. The most dangerous fracture case is where a component completelv fails with a](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_194.jpg)

![Figure 2. Comparison between fracture toughness characteristics under static and cyclic loading: (1) heat resistant steels; (2) chrome—molybdenum steels; (3) titantum alloys; (4) austenitic steel; (5) 20L steel. (Open and solid symbols indicate fulfilment or non-fulfilment of plane strain conditions, respectively; half-solid symbols correspond to the case where plane strain conditions were fulfilled in the K,, determination and not fulfilled in the Kg” determination.) YALIOUS DALCHes dll MWA suenuUy GQUIer it PrOperues, Figure 2 compares the static and a fatigue fracture toughness characteristic of the -onsidered materials, shown in coordinates Ky/Ko"""—Ko""’. This figure presents more lata than Table 2 because we additionally used the results for specimens: of various sizes 30,35,37]; tested at various stress ratios [29,33,35,40]; for plastically prestrained speci- nens [41-43]; specimens of titanium alloy with different content of nitrogen and oxygen mpurities [53]; and specimens of steel 20L after various service periods [56]. The results of investigation of the influence of these factors on fatigue fracture toughness will be liscussed in the next report.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_195.jpg)

![“—-s values of the stress intensity factor are taken as Ky. Figure 3 compares Kj’ and K,, values for studied materials. It is evident that Kj’ is approximately 20% lower than K;,., and scattering of results is relatively small. It was found [46] that scatter in fatigue fracture toughness characteristics is considerably smaller than that in static fracture toughness characteristics. It follows from Fig. 3 that Kp can be predicted by the properly corrected relationship (4). In view of this, Kye! can be consider- ed as a characteristic, which governs the transition from stable to unstable fatigue crack propagation [11,27].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_196.jpg)

![Figure 5 shows a detailed illustration of the pattern of fatigue crack propagation in steel 1SKh2NMFA at 183 K, which precedes the final fracture of a specimen [27].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_198.jpg)

![Figure 9. Schematic representation of un- stable fatigue crack growth. (Points A and B correspond to crack jumps.) Figure 10 compares fracture toughness characteristics of heat resistant and chrome— molybdenum steels under cyclic and dynamic loading. One can see a good correlation between K;. and Kjg. This suggests that fatigue fracture toughness characteristics of materials, similar in properties to those studied herein, can be judged from dynamic frac- ture toughness characteristics and vice versa. Based on the model formulated above, other possible cases of the relationship between fracture toughness characteristics under static, dynamic, and cyclic loading have been discussed in [26,31].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_202.jpg)

![where C; is a constant, V is specimen volume, 58 corresponds to Weibull modulus value. Figure 2. Scale effect in tension, experiments of Richards [1], explained by Weibull theory](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_205.jpg)

![Figure 3. Scale effects in bending, experiments of Richards [1]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_206.jpg)

![Figure 5. Scale effects in cylinder exposed to internal pressure, experiments by Cook [4] Cook [4] has studied scale effect on yield stress of pipe under internal pressure. He used three types of mild steels (designated A, B and C) and pipes of 6 different diameters. Ratio of external and internal diameter was kept constant and equal to 3. Assuming that there is no scale effect in tension he has plotted pressure at yield stress over tensile yield stress versus internal pipe diameter. Noticeable scale effect Cook has attributed to the existence of a critical layer, in which plasticity occurs when yield stress is overcome.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_208.jpg)

![Figure 6. Scale effect on ductile fracture area. Experiments by Chechulin [5]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_209.jpg)

![Figure 9. Scale effects on ductile fracture strain. Experiments by Carassou et al. [10]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_212.jpg)

![Figure 10. Scaling law by Carpinteri, based on defect distribution [12]. Experiments by Sabnis and Mirza [13]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_214.jpg)

![Figure 14. Asymptotic scaling law of Bazant [16] for two asymptotic behaviours: plastic collapse and brittle fracture](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_218.jpg)

![In addition to the size effect, the ligament size also influences fracture toughness. Figure 15 shows the influence of normalized notch length a/W (a is notch length and W is the width) on brittle to ductile transition, depending on temperature, as determined on precracked specimens of cast steel. For decreasing ligament size and increasing ratio a/W, the shift to higher temperatures is obvious [23]. Different master curves for nuclear waste container cast steel indicate clearly that transition temperature fp, is shifted to higher value when the ligament size increases. In the transition regime, fracture toughness increases with decreasing ligament size (Fig. 16).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_220.jpg)

![Figure 27. The applications of Malmberg’s model [22] to Morrison results](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_231.jpg)

![Figure 11. Anodic dissolution model of crack propagation [10]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_247.jpg)

![Figure 10. Schematic representation of the pit growth mechanism [8]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_248.jpg)

![Figure 14. Scheme of typical results obtained by statically loaded smooth samples Tests on statically loaded smooth specimens are usually conducted at various fixed stress levels and time to failure of specimens in the environment is measured. The thresh- old stress R,, is determined when time to failure approaches infinity, Fig. 14. These experiments can be used to determine the maximum stress that can be applied in service without SCC failure, or to evaluate the influence of metallurgical and environmental changes on SCC [11].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_252.jpg)

![obtained with modified techniques combined with microscopy [17]. For example, average stress corrosion crack growth rate can be determined from the depth of the largest crack measured on fracture surfaces of specimens, divided by the time of testing. In this procedure, SC crack is assumed to be initiated at the start of test, which is not always true. On the other hand, fracture mechanics implies that the structure already contains a crack or a crack-like flaw.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_253.jpg)

![Evaluation of SCC by mec usually conducted with either a hanically precracked (fracture mechanics) specimens are constant applied load (Fig. 16a), or with fixed crack open- ing displacement COD, and the actual rate of crack propagation v = da/dt is measured (Fig. 16b). The magnitude of s force for crack propagation) is ress distribution at the crack tip (the mechanica driving quantified by the stress intensity factor K; (in the scope linear elastic fracture mechanics LEFM) for specific crack and loading geometry. As a result, the crack propagation ra e, logda/dt is plotted versus K;. These tests can be made such that Kj, increased with crack length (at constant or gradually rising applied load), decreases with increasing crack length (constant crack opening displacement CO approximately constant as the crack length changes (special tapered samples) [11]. D), or is](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_254.jpg)

![Table 11. Stress in the critical zone [kN/cm’]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/table_019.jpg)

![Table 17. Results of calculation (model, deformation [cm], stress [kN/em’], energy)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_290.jpg)

![2. THE ESTIMATION OF FATIGUE LIFE Unstable crack propagation occurs when one of the stress intensity factors Ky (@= I,JI,II1) is equal or greater than the experimentally determined material property K,. The estimation of fatigue life can be updated for each crack extension. The crack growth equation provides a relation between the crack increment Aa and the increment in the number of load cycles AN. In case of cyclically loaded structures, the number of load cycles equivalent to the crack increment can be determined by a numerical integration of the governing crack growth equation [11]. Te Dad ee Tiascex: Sx or wile Te: lewsk esnes i tieaw sven waenolal &® neanle wenscsth. awante Ane nedndiing be](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_314.jpg)

![In this example [14], a 3-D analysis of the turbine housing is carried out. Using the original design documentation, the 3-D geometrical model of the turbine is generated. In this 3-D object, cracks with different lengths (90-375 mm) and depth (20-40 mm) are assumed and modelled. Calculations are performed to investigate the influence of crack length and depth on the value of maximum effective stress, as well as on the value of stress intensity factor.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_317.jpg)

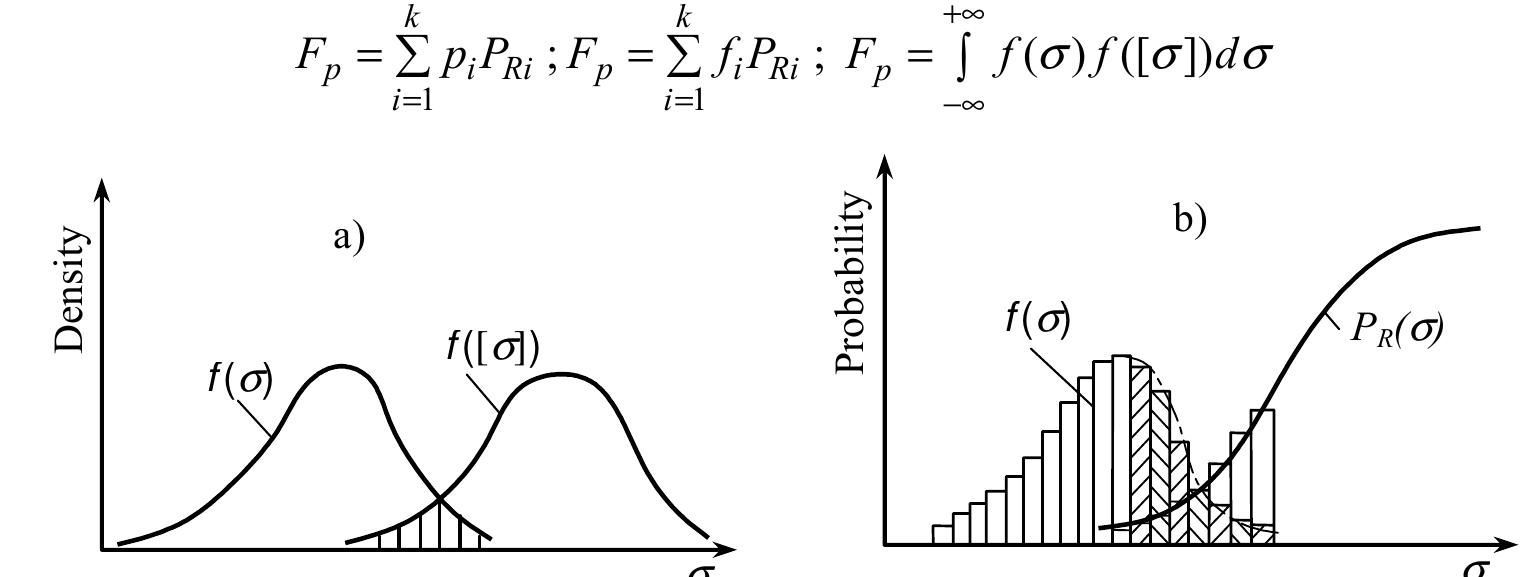

![Figure |. Relation between service stress distribution f(0) and critical stress distribution f([o]) in safety factor determination nor the work stresses are determinant values. The determinant values are stochastic values which dissipate by rule within a wide range (Fig. 1). The safety factor is the ratio of the mean (most probable) value of critical stress and the highest work stress, which can be expected in the work process. There is also a possibility for the occurrence of circum- stances which cannot be foreseen, thus work stress can be somewhat greater, but this is not likely. The machine part has absolutely been used, and the safety in work satisfied, if the safety factor is such that the highest possible value of work stress is lower than the minimal possible value of critical stress. This condition has been satisfied if the dissipa- tion presented in Fig. 1 (curve 1) is covered by the value of the safety factor. This value is S=1.25...2.5. Lower limits may be used when data about the critical and work stresses are well known and reliable.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_322.jpg)

![Figure 7 shows the coordinate system with uniform scale on the coordinates X and Y (upper and right scale). Starting from expressions for X= Ino, and Y= InlIn{I/[l — F(o,)]} and from this uniform scale, values have been calculated for o, and for F(o,), the values of which are given on the lower and left scale. This is how the Weibull’s coordinate system is obtained. Experimental (empirical) values of cumulative probability F(o,) are entered for each class of stress amplitudes o,. A series of points is obtained which follow closely the straight line. After entering, this set of points is approximated by a straight line. Coordinates X and Y enable determination of parameters in the equation of the straight line, a and 6, and t After approximating experimental points by a straight line, the parameter 77 expressed in the stress units is read in the intersection of the straight line with the X axis, i.e. that is the stress value for the probabi thus in expression F(0;,) the ratio o;,/77 is a dimensionless value. Parameter G= 1.3 is the part on the Y axis for AX = The greatest stress fluctuations have the greatest effect on fatigue of the material. The hereby also the parameters of Weibull’s distribution, 7 and 2. ity F(0,) = 0.632. Dimensions of parameter 77 are same as O;, and represents a dimensionless value. where the independent variable x is substituted by the stress amplitude o,. The parameters of this distribution are 7 and f, which may be determined in the simplest way by graphi- cal method. It is necessary to transform Weibull’s function into the form of a straight line for this purpose. This is achieved by double logarithm of the transformed form of Weibull’s function](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_327.jpg)

![The result of final evaluation is shown in Figs. 20 and 21 [21].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_362.jpg)

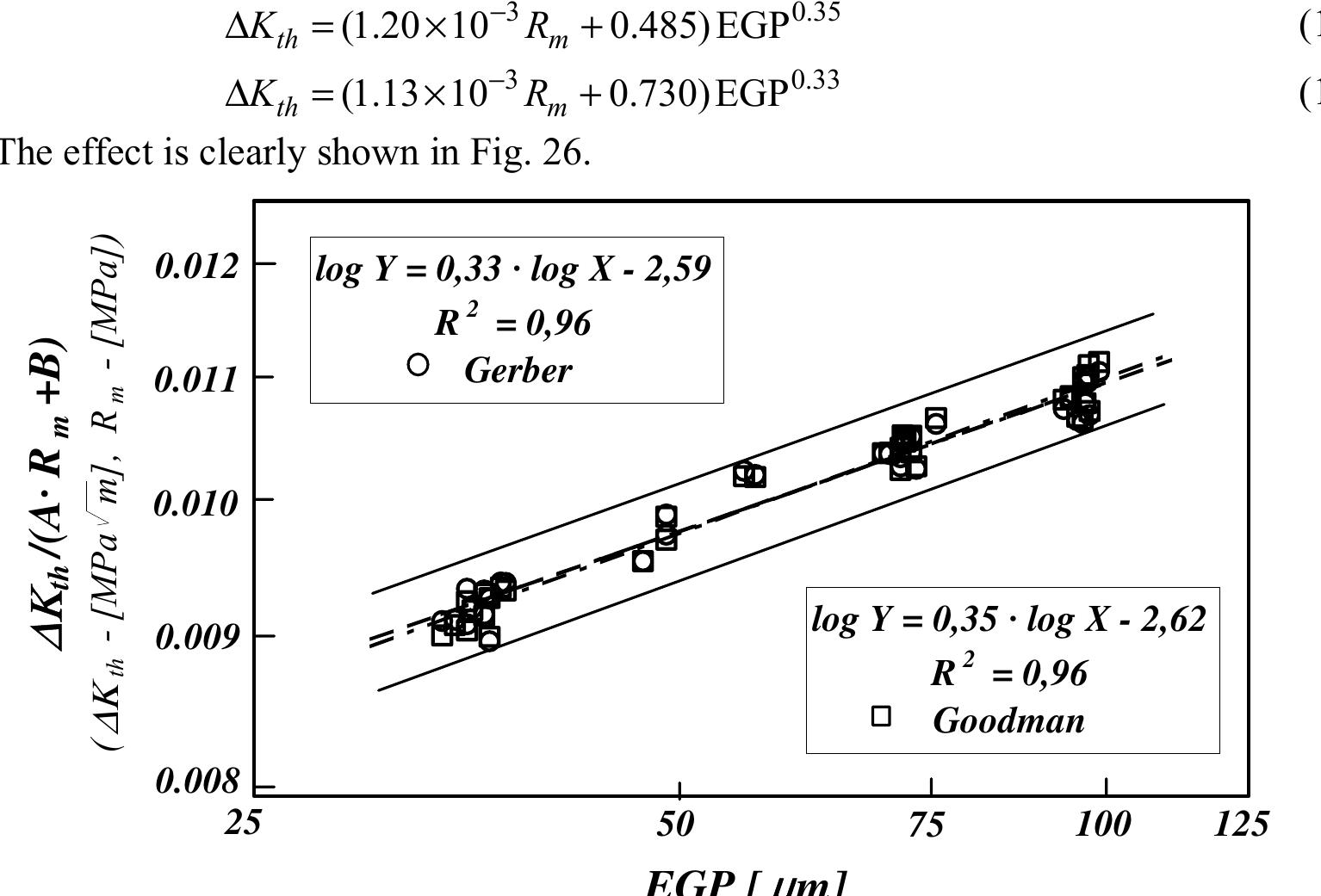

![Figure 23. The fatigue crack propagation rate (left), and three courses of the endurance limit Two types of surface defects were considered: single Vickers indentations and series of Vickers indentations. The size of each indentation was either d=110um or d= 220 um. Both kinds of artificial defects are schematically presented in Fig. 24—left [27,28]. Equivalent geometrical parameters (EGP) of these artificial defects were calcu- lated. Defect size and stress gradient were also taken into account [13]. They are shown in Fig. 24-richt.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_365.jpg)

![Fracture mechanics has brought significant changes in engineering prac example to illustrate this statement, the problem with the Alaska pipeline and ice. As an application of the fracture-safe principle in design may be mentioned. In case of the pipeline from Alaska to the rest of the USA, the fracture mechanics criteria were adopted traditional standards on admissible defects in a welded joint [12]. Namely, instead of when non- destructive testing revealed a large number of defects in round welded joints which, according to the then effective standards, should have been repaired, the ques nomic justification, i.e. necessity of repair, arose. Therefore, the institution ion of eco- in charge,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_369.jpg)

![3.1.1. The analysis of critical defects using the methods of fracture mechanics The defects marked as ‘critical’ were analyzed using methods of fracture mechanics, by applying conservative approach. Therefore, all three were considered as cracks: defects No.970-64 and 978-14 as surface cracks (partially passing through the thickness, while defect No.971-57 was considered a line crack (passing through the entire thick- ness). In this way an extremely conservative assessment was adopted for defect 971-57, in order to check the behaviour of the vessel, even in such a case. id have been eliminated by grinding, with small reduction of thickness at the grinding , which had no significant influence on vessel safety [22]. Jessel No.976 had 5 defects marked as unacceptable, according to Report No.6/98 of a Institute, out of which defects from Photos No.24 and No.38 were again, ultrasoni- y inspected. Based on additional ultrasonic inspection, it was concluded that two slags 1 Photo No.976-24 were not connected, and that the defect from Photo No.976-38 in fact offset or mismatch, i.e. shape defect (507). Having this in mind, as well as the and location of defects found in vessel No.976, it was concluded that all five defects essel No.976 were less dangerous than those marked “critical” in vessels 970 and 971. Jessel No.978 had 5 defects marked as unacceptable, out of which the defect from to No.35 was additionally ultrasonically inspected. Additional ultrasonic inspection ved that dimensions of this defect were not ‘critical’; but incomplete penetration 402, 25 mm long, from Photo No.978-14 was chosen as one of three critical defects, ough additional ultrasonic inspection failed to register it. The width of this defect, the ie of 2 mm was adopted that, according to the documentation of vessel No.978, corre- ided to the predicted size of the weld metal root, and at the same time was the upper itivity limit for ultrasonic examination. as ~~ 4 oe ee ee ee](https://figures.academia-assets.com/70690206/figure_374.jpg)

Key takeaways

AI

AI

- Fracture mechanics provides critical insights into the integrity of materials and structures under stress.

- Neutron irradiation significantly embrittles reactor pressure vessel (RPV) materials, increasing transition temperatures and decreasing toughness.

- Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) and corrosion fatigue are major failure mechanisms influenced by environmental and mechanical factors.

- Fracture mechanics standards, such as ASTM E399, guide the assessment of material toughness and crack behavior.

- The SINTAP procedure offers a systematic approach for flaw assessment in engineering materials, enhancing safety and reliability.

Related papers

International Journal of Fatigue, 1995

Fracture mechanics has evolved into an engineering tool able to solve problems related to the safety of structures containing defects. In practice, however, a wide choice of parallel methods as well as unsolved discrepancies in the theory requires engineering judgement and pragmatism. In this paper a practical case study is presented, concerning a maintenance strategy assessment performed on a welded pressure vessel. The pressure vessel is analysed in terms of leak-before-break arguments, proof test logic, fatigue initiation life, defect initiation and unstable growth critical sizes, fatigue crack propagation that leads to fracture or leakage, as well as probabilistic methods based on defect size distributions and NDE detection probabilities. The paper deals with some background to the theories employed, the different steps of the assessment methodology, as well as with the interpretation of the result to design a practical and safe maintenance strategy.

Metals

An insight of the dominant fracture mechanisms occurring in mechanical metallic components during industrial service conditions is offered through this short overview. Emphasis is given on the phenomenological aspects of fracture and their relationships with the emergent fracture mode(s) with respect to the prevailed operating parameters and loading conditions. This presentation is basically fulfilled by embracing and reviewing industrial case histories addressed from a technical expert viewpoint. The referenced case histories reflected mainly the author’s team expertise in failure analysis investigation. As a secondary perspective of the current study, selected failure investigation and prevention methodological approaches are briefly summarized and discussed, aiming to provide a holistic overview of the specific frameworks and systems in place, which could assist the organization of risk minimization and quality enhancement.

Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 1975

AkbwE-Tbestructunlperfo~ceLmpndsplPcedonprescnt&y~perf~cethipsPnd~trpes of sbipbopid liquid natural gas (LNG) cargo containment systems requires the use of new materkls which can perform under higher loadings and severe service environments. Such critical designs must be e while nmint&& a high smmtuml teikbilky and decreased Jiie.cyck costs. For high performance rd@tb-eriricJdesisssunkrcrmpli~witbduarEc_toknatderilnproecdurwwhichprmidefa~tlosd paths and/or crack arrest capabiRir. The ship construction atsd maintenance req&ments must ako be included in the d&n he&se of their e&t on the structutal life performance of the high performance ship. For shipboard LNG cargo containment systems mod&d LEFM (bear elastic fracture meclumks) is used in thedajla-. ThepPpudircus#rthephibropkyofafatiOueradf~~coatrolpiDnforhiOhpuformroce shipsaadthe use of modified LEFM for shipboard LNG cargo containment systems. Current applications of a fatigre and fracture control plan arc discussed. The types of shipboard cargc umtainment systems designed usinB tbe modified LNG approach are described. The paper addresses the need for an integrated life time quality assurance program. Such a program is shown tc require a synthesis of materials characterization, structural analysis and nondestructive testing. A serviceperformance ftedbsckloog,wiUuristuHdeoipaersineoA~improvi~tbc~~v~q~ criteria. In addit& areas requiring further work and possii future applicaticns for fatiftue and fracture analysis wfB be discussed.

Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 1984

An overview of fracture mechanics within the Research Division of a large international steel and engineering company is given. Fracture mechanics principles have been utilized to assess materials performance, structural integrity and component design. Examples are given of the applicability of these principles to steel making support activities and product usage in order to demonstrate the range and value of applications for fracture mechanics.

FUNDAMENTALS OF FRACTURE MECHANICS, 2019

Fracture is a problem that society has faced for as long as there have been man-made structures. The problem may actually be worse today than in previous centuries, because more can go wrong in our complex technological society. Major airline crashes, for instance, would not be possible without modern aerospace technology. Fortunately, advances in the field of fracture mechanics have helped to offset some of the potential dangers posed by increasing technological complexity. Our understanding of how materials fail and our ability to prevent such failures have increased considerably since World War II. Much remains to be learned, however, and existing knowledge of fracture mechanics is not always applied when appropriate. While catastrophic failures provide income for attorneys and consulting engineers, such events are detrimental to the economy as a whole. An economic study [1] and [2] estimated the annual cost of fracture in the U.S. in 1978 at $119 billion which was about 4% of the gross national product. Furthermore, this study estimated that the annual cost could be reduced by $35 billion if current technology were applied, and that further fracture mechanics research could reduce this figure by an additional $28 billion. This research paper will introduce several important means of understanding and dealing with fracture in stressed materials. Keywords: Creep, energy balance, stress intensity, fatigue, fracture 1. Atomistic of Creep Rupture Creep rupture is a conceptually simple mode of failure in which a specimen is subjected to a constant uniaxial stress at constant temperature and humidity, and the time to fracture recorded. The fact that rupture can occur later and perhaps much later than the time of application of stress implies that fracture is a time dependent process in which damage takes place within the specimen and accumulates until the specimen no longer has sufficient strength to prevent total rupture. As a very simple approach to the damage accumulation process, a first-order mechanism might be proposed in which the number of unbroken bonds decreases at a rate proportional to the number of unbroken bonds remaining: where n is the fraction of unbroken bonds remaining and K is a rate constant for the process. In such a process the number of unbroken bonds goes to zero only at t→∞, and clearly fracture will occur well before that. Perhaps a reasonable scaling law would take the creep-rupture lifetime t f to scale with the average time t for a bond scission, which can be computed as: Following another approach which describes yield as a thermally activated stress aided rate process, the bond scission process is viewed similarly and the rate constant K is written as: where E * and V * are an activation energy and volume, and ψ is the stress on the bond. Determining ψ is nontrivial, as ψ obviously varies over the distribution of bonds and is dependent on the material microstructure. But as another approximation, the atomic stress might be taken to scale with the externally applied stress, giving equation 1 below:

1988

The service longevity of complex propulsion systems --such as tile SSMI! --can be at risk from several competing failure modes. Conventional life assessmcnt practice focuses upon the most severely life-limited feature of a given component, even though there may be other, less severe, potential failure locations. Primary, secondary, tertiary failure modes, as well as their associated probabilities, must also be considered. Furthermore, these prob;d3ilities arc functions of accumulated service time. Thus a component may not ahvavs succtm_b to the most severe, or even the most probable failure mode. Propulsion system longevity must be assessed by considering simtlltatwously the actions of, and interactions among, life-limiting influences. These include, but :Jrc not limited to, high frequency fatigue (ttFF), low cycle fatigue (I.CI:) and subsequent crack propagation, thermal and acoustic loadings, and the influence of less-than-ideal nondestructive evaluation (NI)F.). This paper provides an outline for a probabilistic model for service lilb analysis, and reports on progress towards its implementation. The work is being performed by l'ratt & Whitney under NAS8-3690 I.

2015

A probabilistic fracture mechanics model is employed to estimate the failure probability of axially cracked steam generator tubes. The model estimates the failure probability from the random changes of the influencing parameters such as tube and crack geometry, material properties and non-destructive examination results, reliability and sizing accuracy and stable crack propagation. The performance of the model is illustrated by a numerical example. A steam generator tubing severely affected by the stress corrosion cracking is studied during most unfavourable accidental conditions. Two different plugging approaches are analyzed and the quality is compared, showing the superior performance of crack length oriented approach over tube wall thickness reduction both in terms of SG failure probability and extent of plugging. Thus, apart from setting the acceptable SG failure probability, all elements for the risk-based SG lifetime optimisation are provided on the example of stress corrosion cracking in the tube expansion transition zone. ' Corresponding a u [ l i o r. Tcl. t386 61 lSS5 450, fax +356 61 374 919.

Structural Integrity and …, 2011

Materials Science, 1998

which are the main structural units of the ESIS. Each Technical Committee had reviewed and selected the submitted presentations and, on this basis, formed the topics of the conference program. Every block of topics contained one or two invited lectures, and numerous oral and poster presentations.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (390)

- Kanninen, M.F., Advanced fracture mechanics, Oxford Engineering Science Series, Oxford University Press. (1985)

- Griffith, A.A, The Phenomena of Rupture and Flow in Solids, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, A221, pp. 163-197, (1921); and The Theory of Rupture, Pro- ceedings of the First International Conference of Applied Mechanics, Delft. (1924)

- Griffith, A.A, The Theory of Rupture, Proceedings of the First International Conference of Applied Mechanics, Delft, pp. 55-63, Biezeno and Burgers ed. Waltman. (1925)

- Inglis, C.E., Stresses in a Plate Due to the Presence of Cracks and Sharp Corners, Transac- tions of the Institute of Naval Architects, 55, pp. 219-241. (1913)

- Bueckner, H.F., The Propagation of Cracks and the Energy of Elastic Deformation, Transac- tions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 80, pp. 1225-1230. (1958)

- Erdogan, F., Stress Intensity Factors, Journal of Applied Mechanics, 50, pp. 992-1002. (1983)

- Sneddon, I.N., The Distribution of Stress in the Neighborhood of a Crack in an Elastic Solid, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, A187, pp. 229-260. (1946)

- Westergaard, H.M., Bearing Pressures and Cracks, Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 61, pp. A49-A53. (1939)

- Irwin, G.R., Analysis of Stresses and Strains Near the End of a Crack Traversing a Plate, Jour- nal of Applied Mechanics, 24, pp. 361-364. (1957)

- Sih, G.C., Paris, P.C., and Erdogan, F., Crack Tip Stress-Intensity Factors for Plane Extension and Plate Bending Problems, Journal of Applied Mechanics, 29, pp. 306-312. (1962)

- Sih, G.C., Paris, P.C., and Irwin, G.R., On Cracks in Rectilinearly Anisotropic Bodies, Interna- tional Journal of Fracture Mechanics, 1, pp. 189-203. (1965)

- Elliott, H.A., An Analysis of the Conditions for Rupture Due to Griffith Cracks, Proceedings of the Physical Society, 59, pp. 208-223. (1947)

- Cribb, J.L., and Tomkins, B., On the Nature of the Stress at the Tip of a Perfectly Brittle Crack, Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solid, 15, pp. 135-140. (1967)

- Goodier, J.N., Mathematical Theory of Equilibrium Cracks, Fracture, H. Liebowitz (ed.), Vol. II, Academic, New York, pp. 1-66. (1968)

- Rice, J.R., A Path Independent Integral and the Approximate Analysis of Strain Concentration by Notches and Cracks, Journal of Applied Mechanics, 35, pp. 379-386. (1968)

- Gehlen, P.C., and Kanninen, M.F., An Atomic Model for Cleavage Crack Propagation in Alpha Iron, Inelastic Behavior of Solids, M.F. Kanninen et al.(ed.), McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 587-603. (1970)

- Weiner, J.H., and Pear, M., Crack and Dislocation Propagation in an Idealized Crystal Model, Journal of Applied Physics, 46, pp. 2398-2405. (1975)

- Ashurst, W.T., and Hoover, W.G., Microscopic Fracture Studies in the Two-dimensional Triangular Lattice, Physical Review B, 14, pp. 1465-1473. (1976)

- Markworth, J.A., Kahn, L.R., Gehlen, P.C., and Hahn, G.T., Atomistic Computer Simulation of Effects of Hydrogen and Helium on Crack Propagation in BCC Iron, Res. Mechanica, 2, pp. 141-162. (1981)

- Irwin, G.R, Kies, J.A., and Smith, H.L., Fracture strengths relative to onset and arrest of crack propagation, Proceed. of the American Society for Testing Materials, 58, pp. 640-657. (1958)

- Wells, A.A., Applications of fracture mechanics at and beyond general yielding, British Weld- ing Journal, 10, pp. 563-570. (1963)

- Dugdale, D.S., Yielding of steel sheets containing slits, Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 8, pp. 100-108. (1960)

- Muskhelisvili, N.I., Some Basic Problems in the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, Nordhoff, the Netherlands. (1954)

- Barenblatt, G.I., The Mathematical Theory of Equilibrium of Crack in Brittle Fracture, Advan- ces in Applied Mechanics, 7, pp. 55-129. (1962)

- Eshelby, J.D., The Continuum Theory of Lattice Defects, Solid State Physics, Vol.3, Academic Press. (1956)

- Rice, J.R., The Mechanics of Crack Tip Deformation and Extension by Fatigue, Fatigue Crack Growth, ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ., p.415. (1967)

- Williams, M.L., On the Stress Distribution at the Base of a Stationary Crack, Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 24, No.1, Trans. ASME, Vol. 79, Mar. 1957, pp. 109-114.

- Irwin, G.R., Fracture Mechanics, Structural Mechanics (Proceeding of first Naval Sympo- sium), Pergamon Press. (1960)

- Rice, J.R., Mathematical Analysis in the Mechanics of Fracture, Treatise on Fracture, Vol.2, ed. Liebowitz, H., Academic Press.

- Hutchinson, J.W., Fundamentals of the Phenomenological Theory of Nonlinear Fracture Mechanics, Journal of Applied Mechanics, 50, pp. 1042-1051. (1983)

- Sanders, J.L., On the Griffith -Irwin Fracture Theory, Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol.27, No.2, Trans. ASME, Vol. 82, Series E, June 1960, pp. 352-352.

- Thomas, A.G., Rupture of Rubber, II, The Strain Concentration at an Incision, Journal of Polymer Science, Vol. 18. (1955)

- Rice, J.R., Drucker, D.C., Energy Changes in Stressed Bodies Due to Void and Crack Growth, International Journal of Fracture Mechanics, Vol.3, No.1. (1967)

- Bowie, O.L., Neal, D.M., The Effective Crack Length of an Edge Notch in a Semi-Infinite Sheet Under Tension, International Journal of Fracture Mechanics.

- Rice, J.R., Stresses Due to a Sharp Notch in a Work-Hardening Elastic-Plastic Material Load- ed by Longitudinal Shear, Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol.34, No.2, Trans. ASME, Vol. 89, Series E, June 1967, pp. 287-298.

- Kachanov, L. M., Time of the Rupture Process under Creep Conditions, T.V.Z. Akad. Nauk., SSR, Otd. Tech. Nauk, 9, 26-31. (1958)

- Krajčinović, D., Lubarda, A.V., Šumarac, D., Fundamental Aspects of Brittle Cooperative Phenomena-Effective Continua Models, Mechanics of Materials, 15, 99-115. (1993)

- Rice, J.R., Thermodynamics of the quasi-static growth of Griffith cracks, Journal Mech. Phys. and Solids, 26, pp. 61-78. (1978)

- Shapery, R.A., A theory of mechanical behaviour of elastic media with growing damage and other changes in structures, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 38, 215-253. (1990)

- Janson, J., Hult, J., Fracture mechanics and damage mechanics a combined approach, J. mechanique appliquee, vol.1, 1, pp. 69-84. (1977)

- Hill, R., Aspects of invariance in solids mechanics, Advances in Applied Mechanics, C.S. Yih, ed., Vol. 18, Academic Press, N.Y., pp. 1-75. (1978)

- Chow, C.L., Chen, X.F., An isotropic model of damage mechanics based on edochronic theory of plasticity, Int. J. Fract. 55, pp. 115-130. (1992)

- Cotterell, B., Rice, J.R., Slightly Curved or Kinked Cracks, Int. J. Fract., 16: 155-169. (1980)

- Šumarac, D., Krajčinović, D., A Mesomechanical Model for Brittle Deformation Processes: Part II, J. Appl. Mech., 56, pp. 57-62. (1989)

- Krajčinović, D., Šumarac, D., A Mesomechanical Model for Brittle Deformation Processes: Part I, J. Appl. Mech., 56, pp. 51-56. (1989)

- Horii, H., Nemat-Nasser, S., Overall Moduli of Solids with Micro-Cracks: Load Induced Ani- sotropy, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 31, pp. 155-171. (1983)

- Krajčinović, D., Damage Mechanics, Mech. Mater., 8, pp. 117-197. (1989)

- Šumarac, D., Krajčinović, D., A Self-consistent Model for Microcracks Weakened Solids, Mech. Mater., 6, pp. 39-52. (1987)

- Venecanin, S., Thermal Incompatibility of Concrete Components and Thermal Properties of Carbonate Rocks, ACI Mater. J., 87, pp. 602-607. (1990)

- Šumarac, D., Damage of the Particulate Composite due to Thermal Internal Stresses, ECF11, Mechanisms and Mech. of Damage and Failure, Vol.III, Ed. J. Petit, ESIS, pp. 1913-1918. (1996)

- Šumarac, D., Krasulja, M., Damage of Plain Concrete due to Thermal Incompatibility of its Phases, Int. J. Damage Mech. (1997)

- Ju, J.W., A Micromechanical Damage Model for Uniaxially Reinforced Composites Weakened by Interfacial Arc Microcracks, J. Appl. Mech., 58, pp. 923-930. (1991)

- Foote, M.L.R., Mai, W.Y., Cotterell, B., Crack Growth Resistance Curves in Strain-Softening Materials, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 34, pp. 593-607. (1986)

- Eshelby, J.D., The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion and related problems, Proc. Roy. Soc., A241, pp. 376-396. (1957)

- Mura, T., Micromechanics of defects in solids, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. (1987) REFERENCES

- Inglis, C.E., Stress in a plate due to the presence of cracks and sharp corners, Transactions of the Institute of Naval Architects, 55, pp. 219-241. (1913)

- Griffith, A.A., The phenomenon of rupture and flow in solids, Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society, London A221, pp. 163-197. (1921)

- Irwin, G.R., Analysis of stresses and strains near the end of a crack traversing a plate. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 24, pp. 361-364. (1957)

- Paris, P.C., Gomez, M.P., and Anderson, W.P., A rational analytic theory of fatigue, The Trend in Engineering, 13, pp. 9-14. (1961)

- Elber, W., Fatigue crack closure under cyclic tension, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2, pp. 37-45. (1970)

- Pearson, S., Initiation of fatigue cracks in commercial aluminum alloys and the subsequent propagation of very short cracks, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 7, pp. 235-247. (1975)

- Hobson, P.D., Brown, M., Rios, E.R., Short fatigue cracks, ECF Publication 1, Mechanical Engineering Publications, London, pp. 441-459. (1986)

- Hobson, P.D., The growth of short fatigue cracks in a medium carbon steel, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, UK. (1985)

- Navarro, A., Rios, E.R., A model of short fatigue crack propagation with an interpretation of the short long crack transition, Fatigue Fract. Engng Mater. Struct., 10, pp. 169-186. (1987)

- Miller, K.J., Materials science perspective of metal fatigue resistance, Mater. Sci. Tech., 9, pp. 453-462. (1993)

- Murtaza, G., Akid, R., Modelling short fatigue crack growth in a heat-treated low-alloy steel, Int. J. Fatigue, 17 (3), pp. 207-114. (1995)

- Murtaza, G., Short fatigue crack growth in a high strength spring steel, Ph.D. Thesis, Univer- sity of Sheffield, UK. (1992)

- Angelova, D., Akid, R., A note on modelling short fatigue crack behaviour, Fatigue Fract. Engng Mater. Struct., 21, pp. 771-779. (1998) REFERENCES

- Williams, M.L., On the stress distribution at the base of a stationary crack, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 79, pp. 104-109. (1957)

- Sih, G.C., Rice, J.R., The bending of plates of dissimilar materials with cracks, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 31, pp. 477-482. (1964)

- Rice, J.R., Sih, G.C., Plane problems of cracks in dissimilar media, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 32, pp. 418-423. (1965) 81

- Erdogan, F., Stress distribution in bonded dissimilar materials with cracks, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 32, pp. 403-410. (1965)

- England, A.H., A crack between dissimilar media, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 32, pp. 400-402. (1965)

- Rice, J.R., Elastic fracture mechanics concepts for interfacial cracks, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 55, pp. 98-103. (1988)

- Hutchinson, J.W., Suo, Z., Mixed mode cracking in layered materials, Applied Mechanics, 29. (1992)

- Shih, C.F., Cracks on bimaterial interfaces: Elasticity and plasticity aspects, Material Science and Engineering, A143. (1991)

- Liu C., Lambros, J., Rosakis, A.J., Highly transient elastodynamic crack growth in bimaterial interface: higher order asymptotic analysis and optical experiments, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 41. (1993)

- Veljković, J., Analysis of crack propagation on the bimaterial interface, MS, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Kragujevac. (1998)

- Veljković, J.M., Nikolić, R.R., Edge effect on the coating delamination, Fatigue 2003, 7-9 th April 2003, Cambridge, UK. (2003)

- Veljković, J.M., Nikolić, R.R., Application of the interface crack concept to problem of a crack between the thin layer and the substrate, Facta Universitatis, Series: Mechanics, Automatic Control and Robotics, Vol. 3, No.13, 2003, pp. 573-581. (2003)

- O'Dowd, N.P., Mixed-mode fracture mechanics of brittle/ductile interfaces, Miss-Matching of Welds, ESIS 17, Mechanical Engineering Publications, London, pp. 115-128. (1994)

- Wang, J.S., Suo, Z., Experimental determination of interfacial toughness curves using Brazili- an -nut sandwiches, Acta Metall., 38, pp. 1279-1290. (1990)

- Cao, H.C., Evans, A.G., An experimental study of the fracture resistance on bimaterial inter- face, Mech. Mater., 7, pp. 295-305. (1989)

- Liechti, K.M., Chai, Y.-S., Asymmetric shielding in interfacial fracture under in plane shear, J. Appl. Mech., Vol. 28. (1991)

- Stout, M.G., O'Dowd, N.P., Shih, C.F., Fracture toughness of alumina/niobium interfaces: experiments and analysis, Philosoph. Mag., 66, pp. 1037-1064. (1992)

- Wang, J.S., Fracture behavior of embrittled f.c.c. metal bicrystals and its misorientation depen- dence: Part I -experimental, Acta Metall., Vol. 39, pp. 779-792. (1991)

- Wang, J.S., Anderson, P.M., Fracture behavior of embrittled f.c.c. metal bicrystals and its mis- orientation dependence: Part II -theory and analysis, Acta Metall., Vol. 39. (1991)

- Wang, J.S., Mesarović, S.Dj., Directional dependence of corrosion fatigue of Fe-2.7% Si alloy bicrystals, Acta Metall., Vol. 43, pp. 3837-3849. (1995)

- Rice, J.R., Tensile crack tip fields in elastic-ideally plastic crystals, Mechanics of Materials 6, pp. 317-335. (1987)

- Anderson, P.M., Wang, J.S., Rice, J.R., Thermodynamic and mechanical models of interfacial embrittlement, MECH, 131. (1988)

- Mesarović, S.Dj., Kysar, J.W., Continuum aspects of directionally dependent cracking of an interface between copper and alumina crystals, Mechanics of Materials, pp. 272-280. (1996)

- Bagchi, A., Evans, A.G., The mechanics and physics of thin film decohesion and its measure- ment, Interface Science, 3. (1996)

- Suo, Z., Hutchinson, J.W., Interface crack between two elastic layers, Int. J. Fracture, Vol. 43, pp. 1-18. (1990) REFERENCES

- Перельмутер, A.В., Автоматическая Сварка, 9-10, 107-112. (2000)

- Hertzberg, R.W., Deformation and Fracture Mechanics of Engineering Materials, J. Wiley and Sons, New York. (1996)

- Knott, J.F., Fundamentals of Fracture Mechanics, Butterwords, London. (1973)

- Drobnjak, Dj., Lecture notes, Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy, Belgrade. (1996)

- Burns, K.W., Pickering, F.B., Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute, 202, pp. 899-906. (1964)

- Palmiere, E.J., Garcia, C.I., DeArdo, A.J., Processing, Microstructure and Properties of Micro- alloyed and Other Modern High Strength Low Alloyed Steels, The Iron and Steel Society, Warrendale, Pa, pp. 113-133. (1992)

- Allen, N.P. et al., Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute, 174, pp. 108-120. (1953)

- Mueschenborn, W. et al., Microalloying 95, Ed. M. Korchynsky, The Iron and Steel Society, Warrendale, Pa, pp. 35-48. (1995)

- Philips, R., Duckworth, W., Copley, F.E.L., Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute, 202, pp. 593-600. (1964)

- Petch, N.J., Fracture, ed. B.L. Averbach et al., Technology Press, Cambridge, Mass. pp. 54-67. (1959)

- Hougardy, H.P., Stahl und Eisen, 119, pp. 85-90. (1999)

- Roe, G.L., Notch toughness of steels, Metals Handbook 9 th Edition, Vol.1, pp. 689-709. (1978)

- Tanaka, T., Microalloying 95, Ed. M. Korchynsky, The Iron and Steel Society, Warrendale, Pa, pp. 165-181. (1995)

- Prediction of Steel Production for Year 2000 (in Swedish), Stetsen, 59, No.2, pp. 4-10. (2000) 15.

- Yurioka, N., Document IIW IX-1963-2000 (2000)

- Drobnjak, Dj., Koprivica, A., Fundamentals and Application of Microalloying Forging Steels, Ed. Chester J. van Tyne, G. Krauss and D. Matlock, TMS, Warrendale, Pa, pp. 93-106. (1996) REFERENCES

- Irwin, G.R., Fracture, in Handbuch der Physic VI, Springerverlag. (1958)

- Knott, J.F, Fundamentals of Fracture Mechanics, Butterworth's, London. (1973)

- Pellini, W.S., Evaluation of Principles for Fracture Safe Design of Steel Structures, NRL 6957, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Washington. (1969)

- ASTM E399-83: Standard Test Method for Plane-Strain Fracture Toughness of Metallic Mate- rials, Annual Book of ASTM Standards 1986, Vol. 03.01.

- BS 7448-Part 1:1991, "Fracture mechanics toughness tests -Methods for determination of K Ic , critical CTOD and critical J values of metallic materials" REFERENCES

- Standard Methods of Tension Testing of Metallic Materials, ASTM Designation E8-69, "Annual Book of ASTM Standards," American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia.

- Dieter, G.E., Introduction to Ductility, in: "Ductility," American Society for Metals, Metals Park, Ohio. (1968)

- Standard Method of Test for Young's Modulus at Room Temperature, ASTM Elll-61, op. cit., pp. 409-413.

- Williams, M.L., Analysis of Brittle Behavior in Ship Plates, Symposium on Effect of Tempera- ture on the Brittle Behavior of Metals with Particular Reference to Low Temperatures, ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ., 158, pp. 11-44. (1954)

- Shank, Μ.Ε., A Critical Survey of Brittle Failure in Carbon Plate Steel Structures Other than Ships, ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ., 158, pp. 45-110. (1954)

- Fahey, N.H., Impact Testing of Metals, ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ., 466, pp. 76-92. (1970)

- Augland, Β., Brit. Weld. J., Vol. 9, p. 434. (1962)

- Grabulov, V., Prilog definisanju uticaja hemijskog sastava i debljine lima na pojavu prskotina u zavarenim spojevima čelika NIONIKRAL-70 (A contribution to determine the effect of chemical composition and plate thickness on crack occurrence in welded joints of NIONIK- RAL-70 steel), Master degree theses, Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy, Belgrade. (1986)

- Pellini, W.S., Weld. J., Vol. 50, pp. 915-1095, 147s-162s. (1971)

- Puzak, P.P., Shuster, M.E., Pellini, W.S., Weld. J., Vol. 33, p. 481s. (1954)

- Puzak, P.P., Pellini, W.S., NRL Rept. 5831, Aug. 21, 1962; ASTM Standards, pt. 31, pp. 582- 601, Designation E208-69. (1969)

- Robertson, Τ.S., Engineering, Vol. 172, pp. 445-448; J. Iron Steel Inst. London, vol. 175, p. 361. (1953)

- Pellini, W.S., Puzak, P.P., NRL Rept. 5920, Mar. 15, 1963, and Trans. ASME, Ser. A: J. Eng. Power, vol. 86, pp. 429-443. (1964) REFERENCES

- Blačić, I., Grabulov, V., Veljanovski, B.: Fracture analysis and fractography, IBR, pp. 217- 221. (1998)

- Gerić, K.: Crack initiation and propagation in HSLA welded joint, Doctoral thesis, in Serbian. (1997)

- ASM Metals Handbook, 9 th Ed., Vol.1, ASM (1987)

- Kim, B.C., Lee, S., Kim, N.J., Lee, D.Z.: Microstructure and local brittle zone phenomena in high strength low alloy steel welds, Met. Trans., Vol. 22A, pp. 139-149. (1991)

- Davis, C.L., King, J.E., Toughness comparison between the intercritically reheated coarse grained HAZ of two HSLA steels, ICF 8, Kiev. (1993) REFERENCES

- Agatonović, P., Development of residual strength evaluation tool based on stress-strain appro- ximation, International Journal of Fracture, 98, pp. 129-152.

- Agatonović, P., Procena integriteta i veka na osnovu analize podržane eksperimentima, Sedma medj. letnja škola mehanike loma, Ed. S. Sedmak i A. Sedmak, Velika Plana, Jun 1997.

- Agatonović, P., Različite strategije u cilju odredjivanja garantovane preostale čvrstoće i veka, Integritet i vek konstrukcija (2/2001), str. 75-89.

- Redmond G., From 'Safe Life' to Fracture Mechanics -F111 Aircraft Cold Temperature Proof Testing at RAAF Amberley, NDTSL-DGTA, RAAF Base Amberley, QLD.

- Kirk, M.T., The second ASTM/ESIS symposium on constraint effects in fracture; an Overview, Int. J. Press. Vess. & Piping, 64, pp. 259-275. (1995)

- Ritchie, R.O., Suresh, S., Some consideration on fatigue crack closure at near-threshold stress intensities due to fracture surface morphology, Metallurgical transaction, Vol. 13A, May 1982, pp. 937-940.

- Kumar, V. et al., An Engineering Approach for Elastic-Plastic Fracture Analysis, EPRI NP- 1931, Palo Alto, CA.

- Chell, G. et al, Significant Issues in Proof testing: A Critical Appraisal, NASA CR-4628, 1994.

- Agatonović, P., Taylor, N., Life Assessment Technology for Creep-Fatigue Situation Based on Damage Incubation, Fracture Mechanics Application in Lifetime Estimation of Power Plant Components, 26-30 May 1989, Dubrovnik.

- Agatonović, P., Lifetime temperature dependence of components, European Conference 'Life Assessment of Industrial Components and Structures', Cambridge, 30 Sept/1 Octob. 1993.

- Neubauer, B., Wedel, U., Restlife estimation of creeping components by means of replicas, Advances in Life Prediction Methods, ASME 1983.

- Viswanathan, R., Life assessment of high temperature components -current concerns and research in the US, 'Life Assessment of Industrial Components and Structures', Cambridge, 30 Sept/1 Octob. 1993.

- Schwalbe, K.H., Effect of weld metal mis-match on toughness requirements, International Jour- nal of Fracture, 56, pp. 257-277. (1992) REFERENCES

- Corrosion in power generating equipment, Proc. of 8 th International Brown Bowery Symp. On power generating equipment, Baden, Switzerland. (1983)

- Mars G. Fontana, Corrosion engineering, McGraw Hill International Editions. (1987)

- Šijački Žeravčić, V., Bakić, G., Đukić, M., Anđelić, B., Milanović, D., Model of outages clas- sification and statistical computation applied to tube system of thermal power plants, Preventivno Inženjerstvo, Vol. XI, No.2. (2003)

- Kaplun, Optimizacija nadežnosti energoustanovok, Nauka. (1982)

- Getman, Kozin, Nerazrušajušćij kontrolj, Moskva. (1997) 206 207

- Smith, M., Reliability-Centered Maintenance, McGraw-Hill. Inc., New York. (1993)

- Šijački Žeravčić, V., Anđelić, B., Bakić, G., Đukić, M., Milanović, D., Vlajčić, A., Maksimo- vić, P., Influence of material quality on TPP reliability, Elektroprivreda, Vol. LV, br. 4, str. 64- 71. (2002)