This paper describes the concept of sensor networks which has been made viable by the convergence of microelectro-mechanical systems technology, wireless communications and digital electronics. First, the sensing tasks and the potential... more

others 10. Discussion 987 11. Conclusions 991 References 993

A numerical algorithm integrating the 3N Cartesian equations of motion of a system of N points subject to holonomic constraints is formulated. The relations of constraint remain perfectly fulfilled at each step of the trajectory despite... more

Phaser is a program for phasing macromolecular crystal structures by both molecular replacement and experimental phasing methods. The novel phasing algorithms implemented in Phaser have been developed using maximum likelihood and... more

The previously developed particle mesh Ewald method is reformulated in terms of efficient B-spline interpolation of the structure factors. This reformulation allows a natural extension of the method to potentials of the form 1/r p with... more

The field now called Evolutionary Computation had a slow start. In the late 60s and early 70s a number of researchers in the USA and Germany applied the principles of Darwinian evolution, based on natural selection, for problem solving.... more

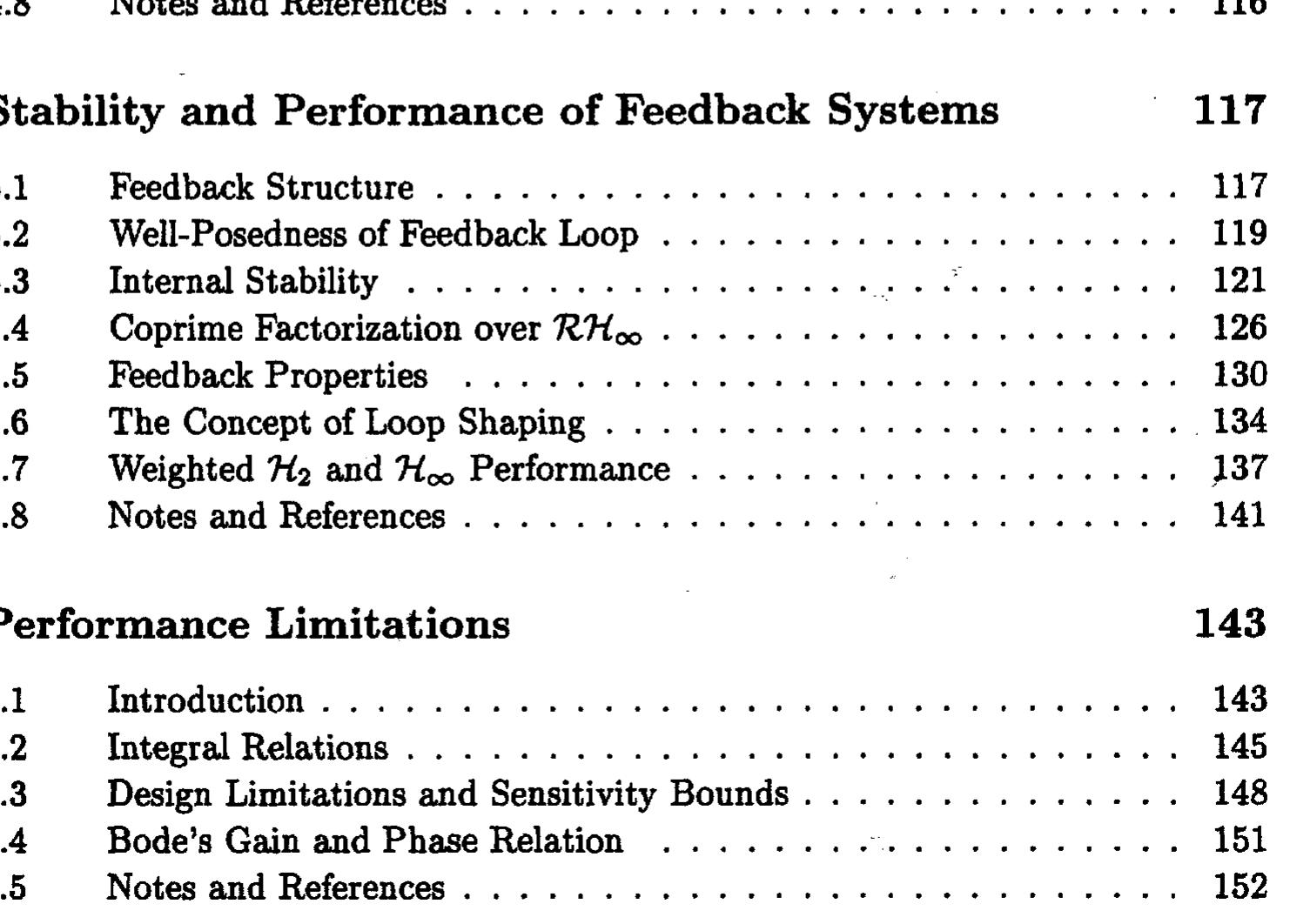

Reduction of a colloidal suspension of exfoliated graphene oxide sheets in water with hydrazine hydrate results in their aggregation and subsequent formation of a high-surface-area carbon material which consists of thin graphene-based... more

This book seeks to integrate research on cause and effect inference from cognitive science, econometrics, epidemiology, philosophy, and statistics+ It puts forward the work of its author, his collaborators, and others over the past two... more

A modification of the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths is presented. One of the images is made to climb up along the elastic band to converge rigorously on the highest saddle point. Also, variable spring... more

The semiconductor ZnO has gained substantial interest in the research community in part because of its large exciton binding energy (60 meV) which could lead to lasing action based on exciton recombination even above room temperature.... more

SIR97 is the integration of two programs, SIR92 and CAOS, the ®rst devoted to the solution of crystal structures by direct methods, the second to re®nement via least-squares±Fourier procedures. Several new features have been introduced in... more

We present a new continuum solvation model based on the quantum mechanical charge density of a solute molecule interacting with a continuum description of the solvent. The model is called SMD, where the "D" stands for "density" to denote... more

Continued use of petroleum sourced fuels is now widely recognized as unsustainable because of depleting supplies and the contribution of these fuels to the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the environment. Renewable, carbon neutral,... more

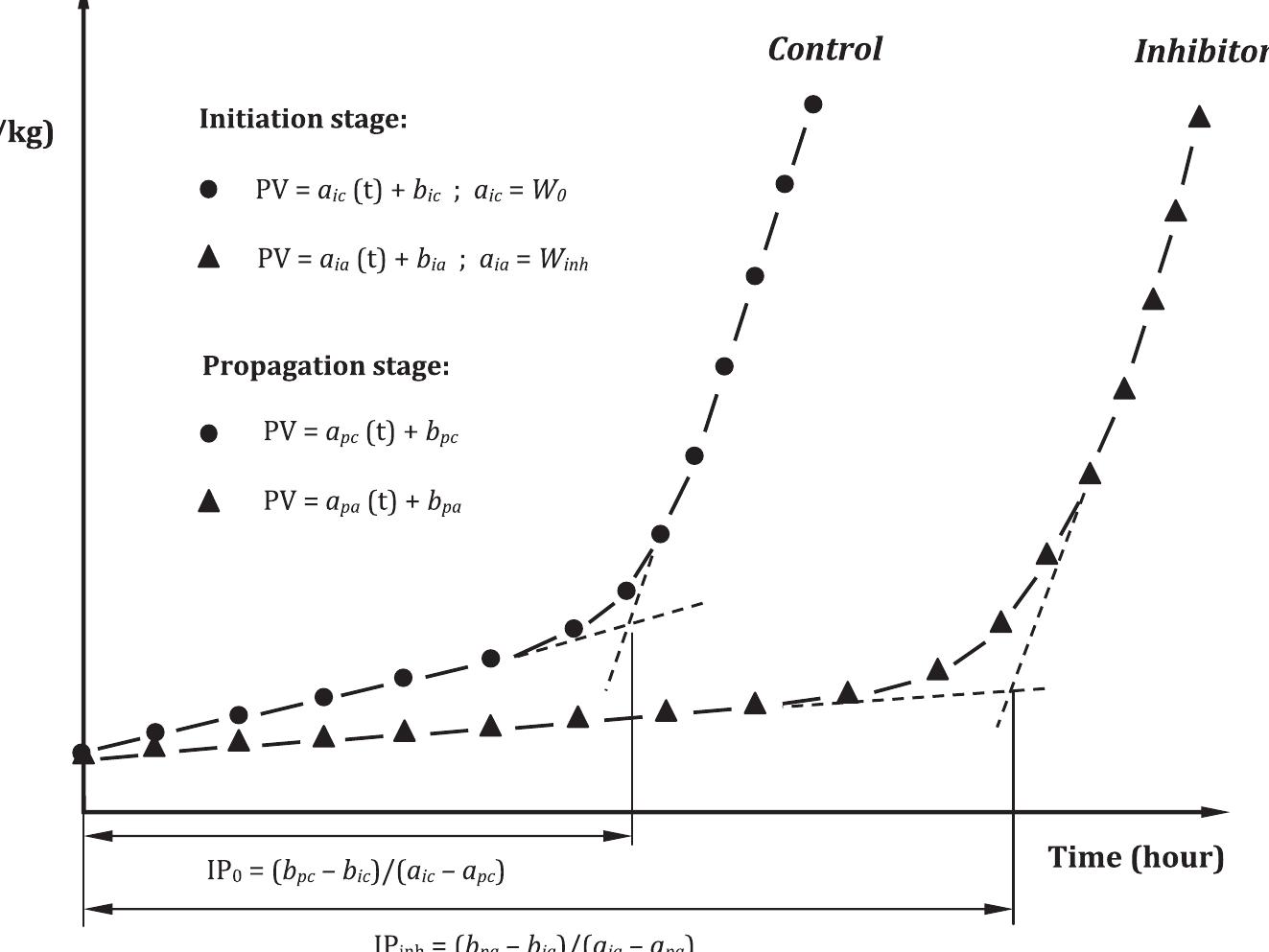

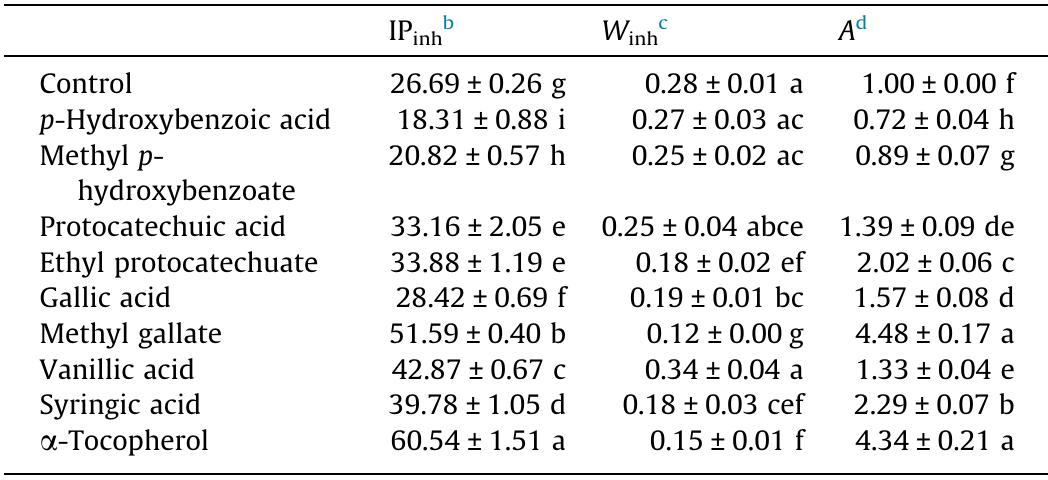

Anti-DPPH radical effect as well as anti-peroxide activity of o-hydroxyl, o-methoxy, and alkyl ester derivatives of p-hydroxybenzoic acid in a bulk fish oil system and its O/W emulsion were investigated. Electronic phenomena, intra-and/or... more

In the paper it is shown that the Balanced Business Scorecard (BSC) allows a balance between financial and non financial objectives and performs a quantification of the dimensions of strategy in four areas -financial, customers, processes... more

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately.

For Abstract see ChemInform Abstract in Full Text.

Model predictive control is a form of control in which the current control action is obtained by solving, at each sampling instant, a "nite horizon open-loop optimal control problem, using the current state of the plant as the initial... more

The program Mercury, developed by the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, is designed primarily as a crystal structure visualization tool. A new module of functionality has been produced, called the Materials Module, which allows... more

Graphical user interfaces (GUIs) simplify use of computers by presenting information in a manner that allows rapid assimilation and manipulation. The use of visual constructs (widgets) that mimic physical objects such as `switches'... more

A new method for modeling surface tension effects on fluid motion has been developed. Interfaces between fluids of different properties, or “colors,” are represented as transition regions of finite thickness, across which the color... more

A method for measuring the surface energy of solids and for resolving the surface energy into contributions from dispersion and dipole-hydrogen bonding forces has been developed. It is bas& on the measurement of contact angles with water... more

Multilevel inverter technology has emerged recently as a very important alternative in the area of high-power medium-voltage energy control. This paper presents the most important topologies like diode-clamped inverter (neutral-point... more

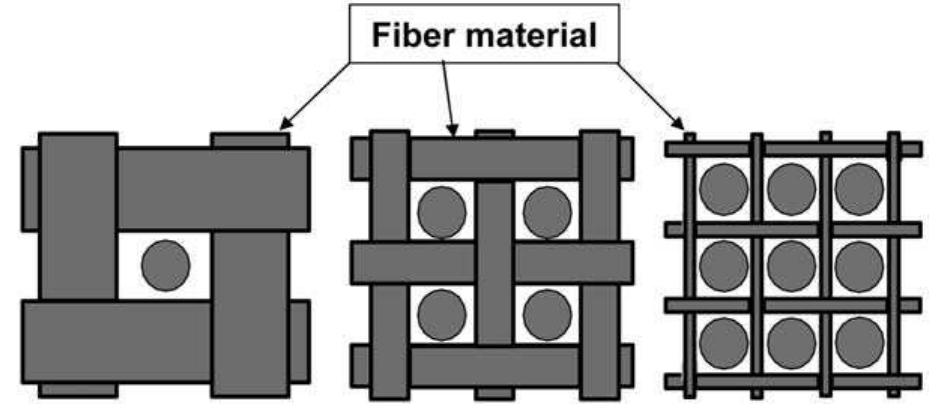

Electrospinning has been recognized as an efficient technique for the fabrication of polymer nanofibers. Various polymers have been successfully electrospun into ultrafine fibers in recent years mostly in solvent solution and some in melt... more

Although this book is primarily intended for students in physical sciences and engineering, the experienced researcher will also find it a most valuable reference.

Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 324, 301-313 (1971) Printed in Great Britain ... Surface energy and the contact of elastic solids ... BY KL JOHNSONt, K. KENDALL: AND AD ROBERTS? t University Engineering Department, Cambridge, England S Surface ...

Most Brain–Computer Interface (BCI) research aims at helping people who are severely paralyzed to regain control over their environment and to communicate with their social environment. There has been a tremendous increase in BCI research... more

We present an overview of the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM), a parallel and efficient algorithm for simulating single-phase and multiphase fluid flows and for incorporating additional physical complexities. The LBM is especially useful... more

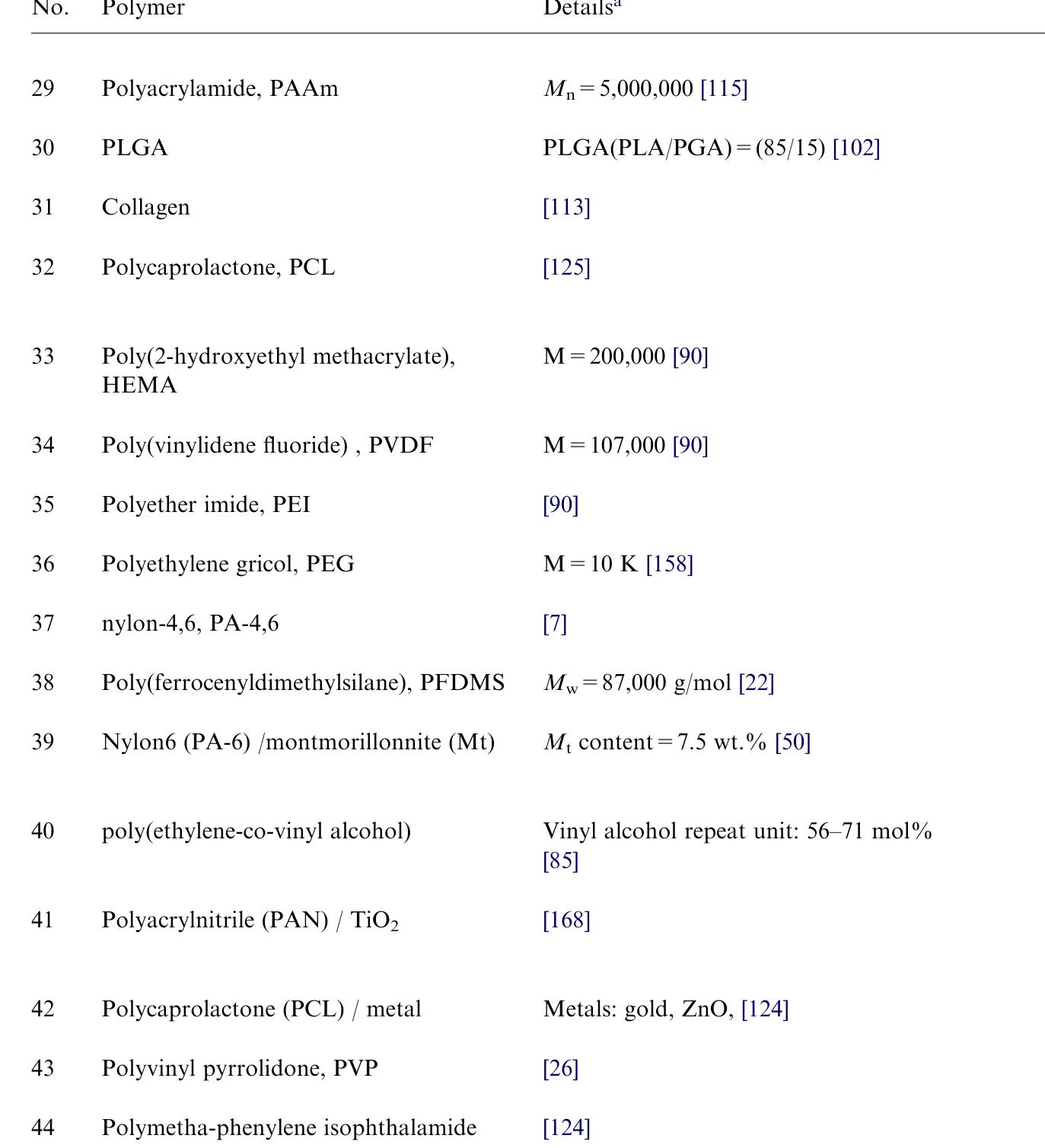

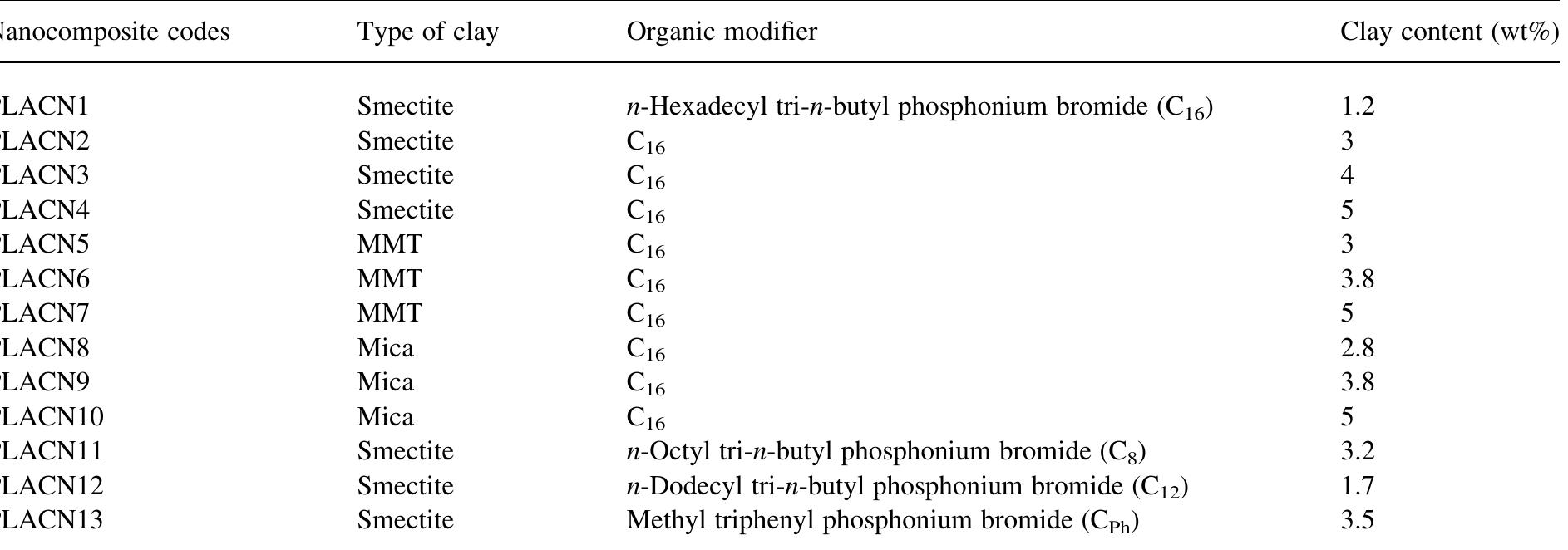

A review is given of the academic and industrial aspects of the preparation, characterization, materials properties, crystallization behavior, melt rheology, and processing of polymer/layered silicate nanocomposites. These materials are... more

![Fig. 6. The SPIN protocol [35]. message, the sensor broadcasts an ADV message containing a descriptor, i.e., meta-data, of the DATA as shown in Step | of Fig. 6. If a neighbor is interested in the data, it sends a REQ message for the DATA and DATA is sent to this neighbor sensor node as shown in Steps 2 and 3 of Fig. 6, respectively. The neighbor sensor node then re- peats this process as illustrated in Steps 4, 5, and 6 of Fig. 6. As a result, the sensor nodes in the entire sensor network, which are interested in the data, will get a copy.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/7243243/figure_006.jpg)

![Fig. 7. An example of directed diffusion [39]: (a) propagate interest, (b) set up gradient and (c) send data.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/7243243/figure_007.jpg)

![Fig. 2. A) Structural model of the linear chain contained in LiMogSe¢ molecular wires that is formed by staggered stacking the triangular planar (Mo3Se3) units. B) A TEM image of bundles assembled from (Mo¢Se¢)” molecular wires in the presence of polymerizable cationic surfactants such as w-undecenyltrimethy- lammonium bromide (w-UTAB) [36].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_003.jpg)

![Fig. 3. A) An illustration of the crystal structure of t-Se composed of hexago- nally packed, helical chains of Se atoms parallel to each other along the c-axis. B) A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of t-Se nanowires with a mean diameter of 32 nm. C) A high-resolution TEM image recorded from the edge of an individual nanowire showing well-resolved interference fringe spacing of 0.16 nm that agrees well with the interplanar distance between the {003} lattice planes. D) A TEM image of two t-Se nanowires, indicating the dimensional uni- formity along each wire. The inset shows an electron diffraction pattern ob- tained from the middle portion of an individual nanowire, confirming that the growth direction was along the <001> axis [40].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_004.jpg)

![Fig. 4. A) Schematic illustration of major steps involved in the sonochemical approach to the synthesis of t-Se nanowires: formation of t-Se seeds on the surfaces of a-Se colloids through cavitation; growth of t-Se nanowires at the expense of a-Se colloids; and continuous growth of t-Se nanowires until all a-Se colloids have been consumed. B) An SEM image of t-Se nanowires formed in an ethanol solution after they had grown for ~5 h. C) An SEM image of t-Se nanowires that were directly grown into an interconnected 2D network by sup- porting the sonicated a-Se colloids on the surface of a silicon substrate [43].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_005.jpg)

![Fig. 5. A,B) SEM images of t-Te nanowires and nanorods synthesized using a solution-phase method similar to that demonstrated for selenium [46]. C) An SEM image of t-Te nanotubes that were synthesized by reducing orthotelluric acid with ethylene glycol at 197°C [48]. D) An SEM image of Seg.5Teo.5 nano- rods that were synthesized by reducing a mixture (1:1) of selenious acid and orthotelluric acid with hydrazine [49]. The primary difference between Se and Te systems is that Te atoms can form nuclei without the need for cooling of the solution. As a result, there are two types of Te product formed at the outset of this redox reaction: a-Te colloids and t-Te seeds (in the form of nanocrystallites). The transfer of materi- al from the amorphous to the crystalline phase is essentially the same for both Se and Te. Because nucleation events might continuously occur in the reduction of orthotelluric acid, it was harder to control the monodispersity of the tellurium nanowires. Nevertheless, the t-Te nanowires prepared using this reaction were characterized by a relatively narrow distri- bution in size, with a typical standard deviation of <10% (Fig. 5A).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_006.jpg)

![Fig. 6. Schematic illustrations of procedures that generated 1D nanostructures by A) shadow evaporation [58]; B) reconstruction at the bottom of V-grooves [60]; C) cleaved-edge overgrowth on the cross-section of a multilayer film [64]; and D) templating against step edges on the surface of a solid substrate [68]. Relief structures present on the surface of a solid substrate can serve as a class of natural templates for generating sup- ported 1D nanostructures. In this regard, microstructures that could be conveniently patterned on the surface of a solid sub- strate using lithography and etching could be exploited as templates to fabricate nanowires made of various materials.©7! Decoration of these templates (usually their edges) with a dif- ferent material, for example, provides a powerful route to the formation of nanowires from various metals and semiconduc- tors.°*) As shown by Jorritsma and co-workers, metal nano- wires as thin as 15 nm could be prepared by shadow sputter- ing (Fig. 6A) a metal source against an array of V-grooves etched on the surface of a Si(100) wafer." In another proce- dure, metal or semiconductor was applied at normal incidence](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_007.jpg)

![Fig. 7. Schematic drawings illustrating the formation of nanowires and nano- tubes by filling and partial filling the pores within a porous membrane with the desired material or a precursor to this material [70,79]. Channels in porous membranes provide another class of templates for use in the synthesis of 1D nanostructures (Fig. 7). This method was pioneered by Martin and several others.'! Two types of porous membranes are commonly used in such syntheses: polymer films containing track-etched](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_008.jpg)

![Fig. 10. A) TEM image of a TiO2/SnO, nanotape obtained through epitaxial growth of TiO, on a single-crystalline SnOz nanobelt. B) A high-resolution TEM image of the atomically sharp TiO2/SnO, interface. The fringe spacings of 4.64 and 4.84 A correspond to the interplanar distances between the (010) planes of TiO, and SnO,j (in the rutile structure), respectively. The insets show electron diffraction patterns taken from each side of the interface along the same zone axes of [102]. C) Compositional line profile across the TiOz/SnO, in- terface in the direction perpendicular to the long axis of the nanotape [104]. Fig. 9. A) TEM images of Ag/SiO, coaxial nanocables that were prepared by directly coating silver nanowires with an amorphous silica sheath using the sol— gel method. B) A TEM image of silica nanotubes prepared by selectively dis- solving the silver cores of Ag/SiO, nanocables in an ammonia solution with ~pH 11 [103].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_010.jpg)

![Fig. 11. A) SEM images of Pd nanotubes generated by reacting silver nanowires with an aqueous Pd(NO3), solution. The nanotubes were broken via sonication for a few minutes to expose their cross-sections. B) A TEM image of Au nano- tubes prepared by reacting silver nanowires with an aqueous HAuCl, solution. The inset shows a high-resolution TEM image of the edge of an individual gold nanotube, indicating its highly crystalline structure and uniformity in wall thick- ness [112].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_012.jpg)

![Fig. 12. A) An SEM image of a-Ag2Se nanowires obtained by reacting t-Se na- nowires with an aqueous AgNO; solution. B) A TEM image of a-Ag»Se nano- wires and the electron diffraction pattern (inset) taken from the middle portion of an individual nanowire. The diffraction spots can be indexed to the ortho- rhombic structure. C) A high-resolution TEM image obtained from the edge of an individual wire, indicating its single crystallinity. The fringe spacing of 0.35 nm corresponds to the interplanar distance of {200} planes, implying that the growth direction of this nanowire was <100>. D) A TEM image of an a- Ag,Se nanowire of ~50 nm in diameter. This wire was crystallized in the tetrag- onal structure, as revealed by its electron diffraction pattern (inset) [113].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_013.jpg)

![Fig. 13. A) An SEM image of SnO, nanobelts synthesized by heating its commer- cial powders at 1000°C. B) A cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy image of these nanobelts, confirming their quasi-rectangular cross-sections [104,120].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_014.jpg)

![Fig. 14. A) SEM and B) TEM images of CuO nanowires synthesized by heating a copper wire (0.1 mm in diameter) in air to a temperature of 500°C for 4 h. Each CuO nanowire was a bicrystal as shown by its electron diffraction pattern and high-resolution TEM characterization (C) [126]. D) SEM and E) TEM images of uniform MgO nanowires (~ 150 nm in diameter) that were synthe- sized by heating MgB, powders in a flow of H2/Ar mixture (1:10 by volume) to a temperature of ~900°C. The inset in (E) shows an electron diffraction pattern [127]. In several related studies, Yang and co-workers synthesized CuyS nanowires by oxidizing copper into Cu2O with O2 gas and then sulfidizing this oxide intermediate into Cu2S with H>S gas under ambient conditions.!’*! Xia and co-workers demonstrated the synthesis of CuO nanowires by heating cop- per substrates (foils, grids, and wires) in air.’?° Figure 14A and B show the SEM and HRTEM images, respectively, of a typical example that was formed on the surface of a milli- meter-sized copper wire. Both electron diffraction and HRTEM studies implied that each CuO nanowire was a bi-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_015.jpg)

![Fig. 16. The birth of a Ge nanowire on a Au nanocluster, as observed using in- situ TEM. It is clearly seen that the Au nanocluster started to melt after the formation of Ge—Au alloy, and this was followed by an increase in the liquid droplet size during the Ge vapor condensation process. When the droplet was supersaturated with the Ge component, a Ge nanowire grew out of this droplet of Au-Ge alloy and became longer as time elapsed [135].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_017.jpg)

![Fig. 17. A) SEM and B) TEM images of Ge nanowires prepared using the chemical vapor-transport method. Insets in (B) show the Au tip of a Ge nano- wire and the electron diffraction from an individual Ge nanowires. C) The atomically resolved TEM image of a Ge nanowire [131a].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_018.jpg)

![Fig. 18. Schematic illustration showing the growth of a nanowire through the so- lution-liquid-solid mechanism [136], which shares many similarities with the vapor-liquid-solid process depicted in Figure 15. Based on an analogy to the VLS process, Buhro and co- workers developed a solution—liquid—solid (SLS) method for the synthesis of highly crystalline nanowires of III-V semicon- ductors at relatively low temperatures (Fig. 18).!97! In a typi- cal procedure, a metal (e.g., In, Sn, or Bi) with a low melting point was used as the catalyst, and the desired material was generated through the decomposition of organometallic pre- cursors. The product was essentially single-crystalline whis- kers or filaments with lateral dimensions of 10-150 nm and engths up to several micrometers. In principle, one could re- duce the operation temperature to a value below the boiling points of commonly used aromatic solvents. For example,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_019.jpg)

![Fig. 19. Schematic illustration of major experimental steps involved in the prep- aration of silver nanowires through a polyol process with Pt nanoparticles as the seeds: A) Formation of bimodal silver nanoparticles through heterogeneous nucleation on Pt seeds and homogeneous nucleation; B) evolution of rod- shaped Ag nanostructures as directed by the capping reagent, poly(vinyl pyrro- lidone); and C) growth of the Ag nanorods into wires at the expense of small Ag nanoparticles [151]. Xia and co-workers recently demonstrated a polyol method that generated silver nanowires by reducing silver nitrate with ethylene glycol in the presence of poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP). The key to the formation of 1D nanostructures is the use of PVP as a polymeric capping reagent and the intro- duction of a seeding step. Figure 19 shows a plausible mecha- nism for this process. When silver nitrate is reduced in the](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_020.jpg)

![Fig. 20. A) SEM and B) TEM images of silver nanowires (after purification via centrifugation) tha were synthesized at 160°C. C) High-resolution TEM image of the end of an individual nanowire, with the arrow indicating a twin plane parallel to its long axis. The inset also shows the corresponding con. vergent-beam electron diffraction pattern. Indices without subscript refer to the left side of the nano. wire shown in (C), and indices with subscript “t” refer to the right side. These two patterns have a re flection symmetry about the {111}-type planes. D) An SEM image of silver nanorods synthesized wher the solution was heated at 185 °C, with other conditions kept the same as those for (A-C) [151].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_021.jpg)

![Fig. 21. A,B) Structures that were assembled from 150 nm polystyrene beads (A), and 50 nm Au colloids (B), by templating against 120 nm-wide channels patterned in a thin photoresist film (see the inset) [161a]. C) An L-shaped chain of Au@SiO, spheres assembled against a template (see the inset) patterned in a thin photoresist film [161c]. D) A spiral chain of polystyrene beads that were assembled by templating against a V-groove etched in the surface of a Si(100) wafer [161d]. conformation. Note that it has been difficult to generate 1D nanostructures with the spiral morphology shown in Fig- ure 21D using any other method. This approach can be poten- tially applied to building blocks with dimensions below 100 nm, as long as one can fabricate templates with feature sizes on the same scale.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_022.jpg)

![Fig. 22. A) The scanning electron diffraction image of a 2D parallel array of nanobelts (130 nm wide and 100 nm thick) that were fabricated from single- crystalline silicon using near-field optical lithography. B) An SEM image of these silicon nanobelts after they had been oxidized in air at 850°C for ~1 h, and then lifted-off in HF solution. These nanowires had lateral dimensions of ~80 nm and lengths up to ~2 cm. C) An SEM image of rings (~2 um in diame- ter) that were made of single-crystalline Si wires with lateral dimensions of ~110 nm. D) The SEM image of a more complex structure that contained con- necting triangles of Si wires with widths varying from 80 to 120 nm [182]. With the use of simple binary PDMS masks only, it has been possible to fabricate a variety of patterns that consist of lines with fixed width. Xia and co-workers have extended the use of this technique to generate nanostructures of single-crystal- line silicon with controllable dimensions and geometric shapes.''*’! They defined the nanostructures in a thin film of positive-tone photoresist using near-field optical lithography, and then transferred the pattern into the underlying sub- strate—silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer—through RIE. They were able to routinely generate parallel arrays of Si nanowires that were ~130nm in width and separated by ~1 um (Fig. 22A). The diameters of these wires could be further re- duced to the scale of ~ 40 nm by using stress-limited oxidation](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_023.jpg)

![Fig. 23. A) A TEM image of two typical Si/SiGe superlattice nanowires. B) Compositional profiles showing the spatial modulation in Si and Ge contents along the longitudinal axis of a nanowire [186]. Figure 23A shows a scanning transmission electron micros- copy (STEM) image of two such nanowires in the bright-field mode. Along the longitudinal axis of each wire, dark stripes appear periodically, reflecting the alternating deposition of the SiGe alloy and Si segments. Since the electron scattering cross-section of Ge atoms is larger than that of Si atoms, the SiGe alloy block appeared to be darker than the pure Si](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_024.jpg)

![Fig. 24. A set of TEM snapshots that clearly shows the melting, flowing, and welding of two Ge nanowires (encapsulated by a carbon sheath) into a single nanowire [193].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_025.jpg)

![Fig. 25. Room-temperature /-V behavior for a Te-doped (A) and Zn-doped (B) InP nanowire at various gate potentials (courtesy of Professor Charles Lieber at Harvard University). The inset shows the nanowire sitting across two elec- trodes. The diameter of the nanowire was 47 and 45 nm, respectively [202a]. material, the carrier mobility is also suppressed by carrier con- finement along the long axis of a wire and by surface imper- fection. Gold represents another metal whose electron-trans- port properties have been extensively studied in the form of short nanowires as thin as a single, linear chain of atoms.21 Because these wires are extremely short in length (usually a few atoms across, sometimes also referred to as point con- tacts), their conductance has been shown to be in the ballistic regime with the transverse momentum of electrons becoming discrete. The transport phenomena (e.g., conductance quanti- zation in units of 2e7h™') observed in this kind of 1D system are found to be independent of material.?°! As for semicon- ductors, recent measurements on a set of nanoscale electronic devices (Fig. 25) indicated that GaN nanowires as thin as 17.6 nm could still function properly as a semiconductor.2°7!](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_026.jpg)

![Fig. 26. A) I-V behavior for a multiple-junction array formed between four p-type Si nanowires and one n-type GaN nanowire. The four curves represent the I-V response for each of the four junctions. Inset is a scanning electron mi- croscopy image of the multiple-junction device. B) Gate-dependent J-V charac- teristics of a crossed nanowire field-effect transistor. The gate voltage (0, 1, 2, and 3 V) for each I-V curve is indicated. The inset (top left) shows J vs Veate for n-type GaN nanowire (bottom trace) and global back (top trace) gates when the bias is set at 1 V. The transconductance for this device was 80 and 280 nS (V.a=1 V) when a global back gate and nanowire gate was used, respectively. The inset (bottom right) shows the measurement configuration (courtesy of Prof. Charles Lieber at Harvard University) [202b].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_027.jpg)

![Fig. 27. A) Excitation and B) emission spectra recorded from an individual InP nanowire of 15 nm diameter (courtesy of Prof. Charles Lieber at Harvard Uni- versity). The polarization of the exciting laser was aligned parallel (solid line) and perpendicular (dashed line) to the long axis of this nanowire, respectively. The inset plots the polarization ratio as a function of energy [216]. In contrast to that from quantum dots, light emitted from nanowires is highly polarized along their longitudinal axes. As shown by Lieber and co-workers," there exists a striking an- isotropy in the PL intensities recorded in the direction parallel and perpendicular to the long axis of an individual, isolated indium phosphide (InP) nanowire (Fig. 27). The magnitude of polarization anisotropy could be quantitatively explained in](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_028.jpg)

![Fig. 28. A) Schematic illustration of the excitation and detection configuration used for the lasing study. B) SEM image of a 2D array of ZnO nanowires grown as uniaxial crystals on the surface of a sapphire substrate. C) The power-dependent emission spectra recorded from a 2D array of ZnO nanowires, with the excitation energy being below (bottom trace) and above (top trace) the threshold [220]. In a typical set-up for lasing experiments (Fig. 28A), one end of the nanowire was terminated in the epitaxial interface](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_029.jpg)

![Fig. 29. Near-field optical image of an individual lasing ZnO nanowire. Note that the lasing emission is only seen at the two ends of this nanowire [223].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_030.jpg)

![Fig. 30. Dependence of nanowire single-harmonic generation (SHG) signals on the polarization: A) A combined topographical and SHG image of two wires at angle of approximately 90°. The image size is ~13 x 13 wm? and the maximum topographic height is 130 nm. The beam is s-polarized, and incident from the right. B) An SHG image recorded from same region as in (A) with a p-polar- ized incident beam. C) Polarization-dependent SHG data and _ theoretical predictions taken from the wires labeled in (A). The theoretical curves are calculated for the SHG signal and x for a hexagonal crystal [225].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_031.jpg)

![Fig. 31. A) The photoresponse (change in current under a constant bias) of a ZnO nanowire to light exposure at two different wavelengths: 532 and 365 nm. B) Reversible switching of a ZnO nanowire between its low and high conductiv- ity states [227].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_032.jpg)

![Fig 32. A) SEM image showing a SnO, nanobelt spanning across four elec- trodes of a transport measurement device. B) Cycling a nanosensor near its res- olution limit under 365 nm light with a bias of 0.5 V. The concentrations of NO, are indicated. The horizontal bars represent averaged signals. The difference in average signals for these three cycles was 16 % [231]. Yang and co-workers found that the strong photoconduc- tive nature of individual single-crystalline SnO, nanobelts makes it possible to achieve equally favorable adsorption— desorption behavior at room temperature by illuminating the devices with UV light of energy near the SnO, bandgap. They analyzed the optoelectronic response of these nano- wire devices in air and NO, environments in order to evalu- ate their chemical sensing capabilities. Figure 32 shows the conductance response of one nanosensor cycled between](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_033.jpg)

![Fig. 33. The TEM image of a silver nanowire (~ 10 nm in diameter) that broke into short segments during sample preparation. The fragmentation might be caused by strains built up in the nanowire when carbon film on the TEM grid was slighted deformed during solvent evaporation.[234] technical development. There are a number of issues that re- main to be addressed before these materials can reach their potential in core industrial applications. First of all, the chemi- cal/thermal/mechanical stability of 1D nanostructures still needs to be systematically studied and better controlled. As discussed in Section 8.1, when the dimension of nanowires is reduced to a smaller and smaller length scale, their melting point will be significantly reduced in comparison with the bulk material. Their weakened thermal stability may eventually place a limit on the conditions under which they can serve as unctional components or interconnects. It is worth noting that thin nanowires tend to break into shorter segments even at room temperature, a phenomenon that has been known as Rayleigh instability.°°! When deposited on the surface of a solid substrate, a slight difference in the residual stresses of the nanowires and the substrate may cause the nanowires to buckle and then fracture into shorter segments. Figure 33 shows the TEM image of a 10 nm Ag nanowire that was de-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_034.jpg)

![Fig. 34. A) The SEM image of a parallel array of [Mo3Se3].. wires fabricated on a silicon wafer by flowing a dispersion of these wires through microchannels formed between a poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) mold and the substrate. B) The SEM image of a nanowire crossbar junction that was formed by rotating the PDMS mold by 90° and then repeating the procedure as for (A). C) The SEM image of a parallel array of [Mo3Se3].. wires spanning across two gold electrodes [235].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/49830158/figure_035.jpg)

![Figure 4. (a) Photograph of a 50-l1m aperture partially covered by graphene and its bilayer. The line scan profile shows the intensity of transmitted white light along the yellow line. Inset shows the sample design: a 20-um thick metal support structure has apertures 20, 30, and 50 um in diameter with graphene flakes deposited over them; (b) Optical image of graphene flakes with one, two, three, and four layers on a 285-nm thick SiOj-on-Si substrate. Reproduced with permission from!”7] (a) andl®4l (b). Copyright: 2008 American Association for the Advancement of Science (a) and 2007 American Chemistry Society (b).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_005.jpg)

![Figure 8. (a) (Left) Photograph of a polymer poly(m-phenylenevinylene-co-2,5-dioctoxy-p-phenylenevinylene) (pmPV)/1,2-dichloroethane(DCE) solu: tion with GNRs stably suspended in the solution. (Right) Schematic drawing of a graphene nanoribbon with two units of a PmPV polymer chair adsorbed on top of the graphene via 7 stacking; (b and c) AFM images of selected GNRs with 50 nm and 30 nm widths, respectively; (d) Transfe characteristics for a GNR of w = 5 nm (thickness ~ 1.5 nm, ~two layers) and channel length L = 210 nm with Pd contacts. (Inset) The AFM image of this device. Scale bar is 100 nm; (e) /ys-V4s characteristics recorded under various V,, for the device in (d); (f) Measured Ion/log ratios (under Vy, = 0.5 V) for GNRs of various ribbon widths. Reproduced with permission from.!'28l Copyright: 2008 American Association for the Advancement of Science. The bipolar feature of graphene makes its carrier type and concentration sensitive to doping, electrically and/or chemically. A graphene p-n junction has been prepared in which carrier type and density in two adjacent regions were locally controlled by electrostatic gating./3"] A fractional conductance quantiza- tion in the bipolar regime has been observed experimentally!34) and explained by theory.!32] Furthermore, theory has predicted that a graphene p-n junction may be used to focus electrons, for turning the n-p-n junction into a Veselago lens.!"34] Graphene p-n-p junctions with contactless, suspended top gates have been reported.[!34] Graphene is usually p-doped due to adsorbates like H,O. Preparation of n-doped graphene materials by high- power electrical annealing of GNRs!!*>! or high temperature annealing of graphene oxidel*‘! in ammonia (NH3) has been demonstrated. A p-type GNR FET was obtained with an I,,/Io¢ ratio of about 10° after annealing.!'95! Electrochemical doping, realized by adding an electrochemical top-gate on the graphene FET, has been reported and a doping level of up to 5 x 108 cm?](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_009.jpg)

![“igure 10. (a) Photographs of 1 cm? films of stacked graphene (one to four layers) on cover slass slips; (b) Transmittance of n-layer graphene films shown in (a). The inset is the relation- ship between the transmittance, T (%), at A= 550 nm as a function of the number of stacked sraphene layers, n; (c) Sheet resistance of n-layer graphene films as a function of the number »f stacked graphene layers, n; (d) Resistance of graphene/PMMA films with different bending adii and flat-fold cycles. The top left inset shows the photo of bent graphene/PMMA/PET. [he red dashed lines mark the edges of graphene/PMMA film. The top right inset shows the changes of Ry as a function of bending radius. Reproduced with permission from.!”] Copyright: 2009 American Chemistry Society.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_011.jpg)

![Figure 13. (a) Low (top) and high (bottom) magnification SEM images obtained from a fracture surface of composite samples of 0.48 vol.% ‘graphene (phenyl isocyanate treated and 1,1 dimethylhydrazine-reduced graphene oxide) in polystyrene; (b) Electrical conductivity of the polystyrene—‘graphene composites as a function of filler volume fraction. Reproduced with permission from.!"§l Copyright: 2006 Nature Publishing Group. Polymer nanocomposites with GO-derived graphene mate- rials as filler have shown dramatic improvements in properties such as elastic modulus, tensile strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability. Moreover, these improvements are often observed at low loadings of filler evidently due to the large inter- facial area and high aspect ratio of these materials, requiring small amounts of filler to achieve percolation. 75] At 0.7 wt% loading, a solution-mixed PVA-graphene oxide nanocomposite showed a 76% increase in tensile strength and a 62% increase in Young’s modulus; the results were attributed to effective load transfer to the graphene oxide filler via interfacial hydrogen bonding.?! Chemical reduction of graphene oxide in the pres- ence of PVA generated conductive composites with a percola- tion threshold below 1 wt% and produced large shifts in glass transition temperature, T,.!°1°! Large increases in Young’s mod- ulus and a 30 °C shift in T, at only 0.05 wt% loading of a TEGO- PMMA composite were attributed to the onset of rheological percolation and to the crumpled morphology of the highly-exfo- liated platelets.?°%] Nanocomposites of platelets derived from TEGO have shown higher stiffness across all loadings and equal or lower electrical percolation thresholds than carbon black and Novel synthesis and processing methods have produced graphene/‘graphite nanoplatelet’ nanocomposites with large property improvements, unique structures, and some of the lowest percolation thresholds reported to date. For instance, layer-by-layer assembly created conductive PVA-CMG nano- composites?!) while solid state shear pulverization was used to directly exfoliate graphite in PP, doubling the modulus versus the neat polymer.?4! A simple method of coating polymer powder with graphite nanoplatelets prior to melt blending resulted in a dramatic reduction in the percolation threshold of a PP nanocomposite from 7 wt% to 0.1 wt%,?4] while a ‘reduction-extractive’ dispersion technique yielded conductive](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_014.jpg)

![Figure 14. (a) SEM image showing a Cu grain boundary and steps in the Cu substrate surface, 2- and 3-layer thick graphene flakes, and wrinkles in the graphene film. Inset shows TEM images of edges of folded graphene; (b) Optical microscope image of graphene film transferred onto a SiO, (285 nm)-on-Si substrate showing wrinkles, and 2- and 3-layer regions. Reproduced with permission from.!'”] Copyright: 2009 American Association for the Advancement of Science.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_015.jpg)

![Figure 15. A proposed schematic (Lerf-Klinowski model) of graphene oxide structure. Repro- duced with permission from [H. He, J. Klinowski, M. Forster and A. Lerf, Chem. Phys. Lett., 1998, 287, 53-56]. Copyright: 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/6335814/figure_016.jpg)

![Fig. 3. PLLA nanofibers with different diameters and pores [10].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_003.jpg)

![Fig. 5. SEM photographs of electrospun nanofibers from different polymer concentration solutions [48]. Another problem encountered in electrospinning is that defects such as beads Fig. 4, [80] and pores Fig. 3) may occur in polymer nanofibers. It has been found that the polymer concentration also affects the formation of the beads. Fong [48] recognized that higher polymer concentration resulted in fewer beads. In their experi- ments with PEO polymer, the polymer concentrations of 1-4.5 wt.% were used. The resulting fiber membranes were visualized under SEM, and different fiber morphologies were captured, as shown in Fig. 5, in which the lowest viscosity, 13 centipoise, corresponded to 1 wt.% PEO concentration, whereas the highest viscosity, 1250 centipoise, corresponded to 4 wt.% con- Fig. 4. AFM image of electrospun PEO nanofibers with beads [80].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_004.jpg)

![Doshi & Reneker [35] pointed out that by reducing surface tension of a polymer solution, fibers could be obtained without beads. This might be correct in some sense, but should be applied with caution. It has been recognized by [48,105] that the surface tension seems more likely to be a function of solvent compositions, but is negligibly dependent on the polymer concen-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_005.jpg)

![Fig. 6. SEM photographs of PEO nanofibers electrospun under different electrical potentials [28]. Furthermore, adding some filler material into a poly- mer solution can also result in fibers free of beads. Zong et al. realized this while electrospinning biodegradable PLDA polymers [169]. They found that with 1 wt.% salt addition, the resul argued charge density on the electrospinning, bringing more electric charges to the je higher the ele elongation ctrical field, fiber d higher iameters. T . As the charges carried by t ing nanofibers were bead-free. They that the addition of salts resulted in a higher he surface of the solution jet during he jet increased, forces were imposed to the jet under resulting in smaller bead and thinner his, however, does not imply that a applied electrical field could result in fewer beads and smoother nanofibers. In fact, Dei the influence of electrical charge, which was applied for electrospinning, on the morphology of PEO nanofibers [28]. They reported that wi the electrical potential the resulting nanofibers became rougher. Their results are shown in Fig. 6. gated zel et al. investi- h the increase of The idea of incorporating nanoscale fillers into poly- mer solution to electrospin composite nanofibers has been extended to prepare a composite solution of organic and inorganic materials for electrospinning. A number of research groups have tried to yield different such nanofibers in recent years, in making Poly-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_006.jpg)

![Fig. 7. A schematic rotating collector for electrospun ultrafine fibers. In another US Patent 5024789 [8] also for the pro- duction of tubular structures, it was reported that by](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_007.jpg)

![Fig. 8. Aligned collagen [113] and PGA [11] electrospun nanofibers.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_008.jpg)

![Fig. 10. Comparison between polymer [a copolymer of PLA—PCL (75:25)] nanofiber depositions: (a) without and (b) with an auxiliary electrical field.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_010.jpg)

![Fig. 11. (a) A set up used to collect uniaxial nanofibers, (b) PEO fibers thus obtained [149]. nanofiber diameters and residual charges. It should be noted that they collected their aligned fibers with a lin- ear velocity of 22 m/s at the tip of the wheel collector, which is equivalent to a rotating speed as high as 1070 rpm. Unfortunately, no reports on the relationship between alignments and different rotating speeds were provided. Even so, this paper has initiated a useful rou- tine towards fabrication and collection of uniaxially aligned polymer nanofiber yarns. scope. We have noticed that different frame materials result in different fiber alignments. For example, the aluminum frame favors better fiber alignments than a wooden frame. Fig. 13 shows SEM pictures of the fibers obtained using the wooden frame and the aluminum frame respectively with the same frame inclination angle (a) of 60°. As can be seen from the figure, the aluminum frame resulted in much better alignments than the woo- den frame. Further work was done by rotating a multi- frame structure on which the electrospun PEO nanofi- bers could be continuously deposited, as demonstrated in Fig. 14. More investigation is under going to under- stand the alignment characteristics in terms of varying he shape and size of frame rods, the distance between he frame rods, and the inclination angle of a single frame (which will be useful in determining how many sides would be best suitable to construct a polygonal multi-frame structure).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_011.jpg)

![Fig. 14. Continuous as-spun nanofibers deposited on a rotating multi- frame structure. Fong et al. [49] obtained some aligned nylon 6 fibers by rapidly oscillating a grounded frame within the electrospun polymer jets. The fiber alignments are shown in Fig. 15. Unfortunately, no detail of their frame has been reported in the open literature yet. In another approach by [29], it was demonstrated that by using a multiple field technique [Fig. 16(a)] the polymer Fig. 15. Aligned electrospun nylon 6 ultrafine fibers [50].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_012.jpg)

![Fig. 16. (a) A multiple field technique, and (b) aligned PEO fiber yarn obtained [29].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_016.jpg)

![Filtration is necessary in many engineering fields. It was estimated that future filtration market would be up o US $700b by the year 2020 [144]. Fibrous materials used for filter media provide advantages of high fil- ration efficiency and low air resistance [152]. Filtration efficiency, which is closely associated with the fiber fineness, is one of the most important concerns for the filter performance Fig. 19). In the industry, coalescing filter media are studied to produce clean compressed air. These media are required to capture oil droplets as small as 0.3 micron. It is realized that electrospinning is rising to the challenge of providing solutions for the removal of unfriendly particles in such submicron range. Since the channels and structural elements of a filter must be matched to the scale of the particles or droplets that are to be captured in the filter, one direct way of developing high efficient and effective filter media is by using nanometer sized fibers in the filter structure [62]. In general, due to the very high surface area to volume ratio and resulting high surface cohe- sion, tiny particles of the order of <0.5 um can be easily trapped in the electrospun nanofibrous struc-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_018.jpg)

![Fig. 21. (a) SEM of PLLA nanofibers ([10]), (b) TEM of elastin-mimetic peptide fibers (bar represents 3.3 jum) ([71]), and (c) AFM of polyurethane nanofibers ([32]).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475325/figure_021.jpg)

![Fig. 54. Bright field TEM images of PPCNs: (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 7.5 wt% MMT. The dark lines are the cross-sections of silicate layers and the bright areas are the PP-g-MA matrix [303]. Reproduced from Nam, Maiti, Okamoto, Kotaka, Hasegawa and Usuki by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_053.jpg)

![Fig. 2. Arrangements of alkylammonium ions in mica-type layered silicates with different layer charges. Hatch areas are silicate layers [50]. Reproduced from Vaia, Teukolsky and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_002.jpg)

![Fig. 3. Alkyl chain aggregation models: (a) short chain lengths, the molecules are effectively isolated from each other, (b) medium lengths, quasi- discrete layers form with various degree of in plane disorder and interdigitation between the layers and (c) long lengths, interlayer order increases leading to a liquid-crystalline polymer environment. Open circles represent the CH. segments while cationic head groups are represented by filled circles [50]. Reproduced from Vaia, Teukolsky and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. In general, layered silicates have layer thickness on the order of 1 nm and a very high aspect ratio The large variety of polymer systems used in nanocomposites preparation with layered silicate can be conventionally classified as below.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_003.jpg)

![Fig. 4. Schematically illustration of three different types of thermodynamically achievable polymer/layered silicate nanocomposites [391]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Okamoto and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_004.jpg)

![Fig. 6. 2D SAXS (a and c) and WAXS (b and d) patterns for orientation MN (left face), NT (right face) and MT (top face) of films HD603 (a and b) and HD612 (c and d). The numbers in the parenthesis represent the reflections from the following: (a) clay tactoids, (b) modified/intercalated clay (002) plane, (c) unmodified clay (002) plane, (d) clay (110) and (020) plane, (e) polymer crystalline lamellar, (f) polymer unit cell (110) plane (inner ring) and (200) plane (outer ring) [329]. Reproduced from Bafna, Beaucage, Mirabella and Mehta by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_006.jpg)

![Fig. 8. Synthesis of polyimide/clay nanocomposite film [11]. Reproduced from Yano, Usuki, Okada, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc., USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_007.jpg)

![Fig. 10. WAXD patterns of polyimide/clay nanocomposites prepared with: (a) 12CH3-MMT, (b) 12COOH-MMT, and (c) C10A-MMT [11]. Reproduced from Yano, Usuki, Okada, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc., USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_008.jpg)

![Fig. 9. WAXD patterns of: (a) 12CH3-MMT, (b) 12COOH-MMT, and (c) CIOA-MMT [11]. Reproduced from Yano, Usuki, Okada, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc., USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_009.jpg)

![Fig. 12. WAXD patterns of the PVA/MMT nanocomposites as a function of dyyyr- The inset shows the distribution of the MMT intercalated d-spacing for the respective nanocomposites [111]. Reproduced from Strawhecker and Manias by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. At first glance, this dependence of the intercalated structure and d-spacing on the polymer/silicate mass ratio seems to be at odds with the theoretical expectations [21,24]. The equilibrium nanocomposite structure predicted from the thermodynamics corre- sponds to an intercalated periodic nanocomposite with d-spacing around 1.8 nm, which is expected to be independent of the polymer-to-silicate composition [21]. However, thermodynamics can only predict the equilibrium structure. In this case, the nanocomposite structure that they found is actually kinetically](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_011.jpg)

![Fig. 13. WAXD spectra for: (left side) pure 2C18M, PI + 2C18M, PS + 2C18M and PSPI18 + 2C18M hybrids, (right side) for PSPI18 + 2C18M intercalated hybrids with silicate loadings (a) 0.7, (b) 2.1, (c) 3.5, (d) 6.7, and (e) 9.5 wt% [128]. Reproduced from Ren, Silva and Krishnamoorti by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_012.jpg)

![Fig. 14. Chemical structure of the dendrimer analogue of the second pseudo-generation hyperbranched polymer [369]. Reproduced from Plummer, Garamszegi, Leterrier, Rodlert and Manson by per- mission of American Chemical Society, USA. Very recently, Plummer et al. [369] used the following method for the preparation of hyper- branched polymer (HBP)/MMT nanocomposites. The chemical structure of HBP is presented in Fig. 14. Nanocomposites were prepared by introdu- cing the required amount of Na*-MMT to 10g of HBP dispersed in 75 ml of boiling deionized water. The mixture was stirred in air at 50°C. After evaporation of half the water, the resulting gel was transferred to an open silicone rubber mold, and dried in air for 2 days at 50°C. The remaining solid was then dried for another 2 days at 120 °C under vacuum, ground, and pressed into 25 mm diameter 1 mm thick disks at 60°C for WAXD analyses. At high Na‘- MMT contents, WAXD analyses indicated 2.5—2.8,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_013.jpg)

![Fig. 15. WAXD patterns for HBP/Na‘*-MMT blends with different compositions: (a) second pseudo-generation HBP; (b) fourth pseudo-generation HBP [369]. Reproduced from Plummer, Gar- amszegi, Leterrier, Rodlert and Manson by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_014.jpg)

![Fig. 16. XRD patterns of w-amino acid [NH 2(CHz),—,;COOH] modified Na*-MMT [131]. Reproduced from Usuki, Kawasumi, Kojima, Okada, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of Materials Research Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_015.jpg)

![Fig. 17. Swelling behavior of w-amino acid modified mmt by s- caprolactam [131]. Reproduced from Usuki, Kawasumi, Kojima, Okada, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of Materials Research Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_016.jpg)

![Fig. 18. Schematic illustration for synthesis of Nylon-6/clay nanocomposite [132]. Reproduced from Usuki, Kojima, Kawasumi, Okada, Fukushima, Kurauchi and Kamigaito by permission of Materials Research Society, USA. For the preparation of PCL-based nanocomposites, Messersmith and Giannelis [163] modified MMT using protonated aminolauric acid and dispersed the modified MMT in liquid e-caprolactone before](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_017.jpg)

![Fig. 20. TEM images of thin section of nanocomposites: (a) PMMA/SSTN, (b) PMMA/SPN, and (c) PS/SPN. The arrow in panel (a) indicates the oriented collection of STN silicate layers [57]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Taguchi, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_018.jpg)

![Fig. 36. Extent of reaction of a neat resin and resins containing either C30B, EG, or BDMA. The inset shows the same data but for longer reaction [244]. Reproduced from Chen, Poliks, Ober, Zhang, Wiesner and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. Time-resolved high-temperature-XRD was used to probe the expansion behavior of the silicate layers during curing of the nanocomposites. Fig. 37 rep- resents the results for a nanocomposite containing 15 wt% C30B held isothermally at 70 °C. In Fig. 38, the changes in d-spacing are plotted against](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_034.jpg)

![Fig. 34. Phase contrast AFM images of DETDA cured DGEBA containing 5 wt% organoclay [243]. Reproduced from Becker, Varley and Simon by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_035.jpg)

![Fig. 19. WAXD patterns of various monomer/OMLS suspensions and corresponding polymer nanocomposites. The dashed lines indicate the location of the silicate (00/) reflection of OMLS from suspensions and nanocomposites. The asterisk indicates the position of (00/) reflections from suspensions and nanocomposites. The arrows indicate a small shoulder or a weak peak [57]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Taguchi, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_019.jpg)

![Fig. 21. WAXD patterns of various nanocomposites [68]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. the presence of lyophilized smectite clays (each contain 10 wt%). They used three different types of co-monomers (each contain 1 mol%) for the free- radical polymerization of MMA, such as N,N- dimethylaminopropyl acrylamide (PAA), N,N- dimethylaminoethyl acrylate (AEA) and acrylamide (AA). Fig. 21 represents the results of WAXD patterns of various nanocomposites (each containing 10 wt% of SPN clay) and corresponding TEM images are shown in Fig. 22. For PAMA—AEA(1)/SPN10 (see Fig. 22b), the same behavior is observed, but the thickness of the aggregation slightly decreased compared to that of PMMA/SPNI1O (see Fig. 20b). For PMMA—PAA(1)/SPN10 (see Fig. 22c) individual](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_020.jpg)

![Fig. 23. Bright field TEM images of nanocomposites: (a) PMMA-— AEA (3 mol%)/SPN10, and (b) PMMA-AA (3 mol%)/SPN10. SPN content is equal to 10 wt% [68]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_021.jpg)

![Fig. 22. Bright field TEM images of: (a) PMMA/SPN, (b) PAMA-—AEA (1 mol%)/SPN, (c) PMMA-—PAA (1 mol%)/SPN, and (d) PMMA-AA (1 mol%)/SPN. Each contain 10 wt% SPN [68]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_022.jpg)

![Fig. 24. Plots of length vs. thickness of the dispersed clay particles in various copolymer matrices estimated from TEM images. The estimated values are located within the shaded area [68]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_023.jpg)

![Fig. 25. Structures of alkylammonium and alkylphosphonium salts used for the modification of clays [98]. Reproduced from Zhu, Morgan, Lamelas and Wilkie by permission of American Chemical Society. In a recent study, Zhu et al. [98] reported the preparation of PS nanocomposites with three different types of new alkylammonium and alkylphosphonium salt modified MMT(s). Fig. 25 represents the structures of the alkylammonium and phosphonium](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_024.jpg)

![Fig. 27. Schematic illustration of the modification and ion exchange of laponite with [Zr(m-CsHs)2Me(thf)]BPh, and propene polymerization. Details regarding the reagent and conditions are shown in relevant Ref. [281]. Reproduced by Tudor, Willington, O’Hare and Royan by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry, UK. For the synthesis of polyethylene/layered silicate nanocomposites, Bergman et al. [323] used Broo- khart’s single component palladium-based complex {1; [{2,6-Pr5C.H;N=C(Me)C-(M)=NC,H3Pr}-2.6} Pd(CH,)3CO.Me][B(C6H3(CF3)2-3,5)4]}, and the although the diffraction peak broadened slightly, but the increase in Al content and complete disappearance of Si—OH signals from IR-spectra agree with MAO reaction/adsorption inside the layered silicate gal- leries. Upon the addition of the metallocene catalyst ([Zr(-CsHs)Me(THF)]*), a cation exchange reaction occurred between the Na* in the MAO-treated hectorite and the metallocene catalyst as demon- strated by an increase of 0.47 nm in the interlayer spacing, consistent with the size of the species. Details can be shown in Fig. 27. Using a synthetic fluorinated mica-type layered silicate deprived from any protons in the galleries; the catalyst was intercalated directly within the silicate layers without the need of MAO](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_025.jpg)

![Fig. 26. Schematic drawing of the formation of the process of covalently bonded polyimide tethered layered silicates [269]. Reproduced from Leu, Wu and Wei by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_026.jpg)

![Fig. 28. Schematic representation of the modification of fluorohectorite with palladium catalyst and ethylene polymerization [323]. Reproducec from Bergman, Chen, Giannelis, Thomas and Coates by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_027.jpg)

![Polyethylene/layered silicate nanocomposites have also been prepared by the in situ intercalative polymerization of ethylene using the so-called polymerization filling technique [326]. Pristine MMT and hectorite were first treated with trimethy- laluminum-depleted methylaluminoxane before being contacted by a Ti-based constrained geometry cata- lyst. The nanocomposite was formed by addition and polymerization of ethylene. In the absence of a chain transfer agent, ultra HMW polyethylene was pro- duced. The tensile properties of these nanocomposites were poor and essentially independent on the nature and content of the silicate. Upon hydrogen addition, Fig. 29. Mechanistic representation of the fixing of TiCl, between the silicate layers of MMT-—OH [328]. Reproduced from Jin, Park, Im, Kwak and Kwak by permission of Wiley-VCH, Germany.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_028.jpg)

![Fig. 30. TEM image of PE-MMT-—OH diluted with HDPE (8 wt% of MMT-—OR) [328]. Reproduced from Jin, Park, Im, Kwak and Kwak by permission of Wiley-VCH, Germany.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_029.jpg)

![Fig. 32. XRD powder patterns for a freeze-dried [H3N(CH3);;. COOH]*-MMT, (b) [H3N(CH2),;COOH]*-MMT freeze-dried and then heated at 229°C, and (c) clay—polyether nanocomposite containing 5 wt% [H3N(CH>);,COOH]*-MMT [226]. Reproduced from Wang and Pinnavaia by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_030.jpg)

![Fig. 31. WAXD patterns of OMTS powder and uncured OMTS/DGEBA mixture. Top scan was obtained at room tempera- ture following heating of OMTS/DGEBA mixture at 90 °C for Ih [224]. Reproduced from Messersmith and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_031.jpg)

![Epoxy resins and hardener as used for the nanocomposite synthesis [243]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_032.jpg)

![Fig. 33. (a) WAXD patterns of DETDA cured DGEBA nanocomposites containing 0-10 wt% organoclay [243]. Reproduced from Becket Varley and Simon by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. (b) WAXD of DETDA cured TGAP nanocomposites containing 0-10 wt? organoclay [243]. Reproduced from Becker, Varley and Simon by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. (c) WAXD of DETADA cure: TGDDM nanocomposites containing 0-10 wt% organoclay [243]. Reproduced from Becker, Varley and Simon by permission of Elsevie Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_033.jpg)

![ihe curing mechanism for an epoxy—anhyaride system with an alcohol initiator is shown in Fig. 35. Amine catalysts like BDMA were added to the mixture to accelerate the reaction by facilitating the ring opening of epoxy groups. Several published papers indicate that intragallery onium ions can catalyze the epoxy curing reaction and thus lead to favorable conditions for obtaining exfoliated nano- composites. To fully understand this system, Chen et al. [244] verified that the crosslinking reactions in the presence of C30B were due to hydroxy initiation and not due to catalytic reactions. For this reason, the extent of reaction of a resin containing C30B was compared to the extent of reaction for a neat resin and resins containing either EG or BDMA. As seen in Fig. 36, the curing kinetics of the resin—C30B system more closely resembles the curing kinetics of the resin—EG system than that of the resin-BDMA Fig. 35. Schematic illustration of generalized curing reaction involving the epoxy monomer, HHMPA, EG, and BDMA [244]. Reproduced from Chen, Poliks, Ober, Zhang, Wiesner and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_036.jpg)

![Fig. 38. Changes in dj, as a function of the curing time and temperature: (a) 5, (b) 10, and (c) 15 wt% silicate loading. The dashed lines denote the qualitative detection limit of the TT-XRD setup [244]. Reproduced from Chen, Poliks, Ober, Zhang, Wiesner and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_037.jpg)

![Fig. 37. TT-XRD of a resin containing 15 wt% C30B held isothermally at 70 °C [244]. Reproduced from Chen, Poliks, Ober, Zhang, Wiesner and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_038.jpg)

![Fig. 39. WAXD patterns of Na*-MMT, PANI and PANI/Na‘- MMT [342]. Reproduced from Kim, Kim, Choi and John by permission of Wiley-VCH, Germany.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_039.jpg)

![Fig. 41. Representative WAXD of PS35/OMLS hybrid heated to 165 °C for various times. Asterisks indicate the positions of the basal reflections from the pristine OMLS [44]. Reproduced from Vaia, Ishii and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_040.jpg)

![Fig. 40. Schematic depicting the intercalation process between a polymer melt and an OMLS [21]. Reproduced from Vaia and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_041.jpg)

![Fig. 42. Schematic illustration of polymer chains intercalated in OMLS [44]. Reproduced from Vaia, Ishii and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. Further research by Vaia et al. [22] demonstrated the dispersion of various types of OMLS in a PS matrix. Li-fluorohectorite (F) (CEC = 150 mequiv/ 100 g), saponite (sap) (100 mequiv/100 g), and Na*- MMT (880 mequiv/100 g) were accordingly modified using various ammonium cations such as dioctade- cyldimethylammonium (2C18), octadecyltrimethy- lammonium (qC18) octadecylammonium (C18), and a series of primary alkylammonium cations with](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_042.jpg)

![Fig. 44. X-ray diffraction pattern of PEO/Nat-MMT hybrid heated to 80 °C for 0, 2, and 6 h [189]. Reproduced from Vaia, Vasudevan, Krawiec, Scanlon and Giannelis by permission of Wiley-VCH, Germany. The in situ intercalative polymerization technique is generally used to prepare N6/clay nanocomposites. Liu et al. [142] first applied this technique in the preparation of a commercially available N6 with](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_043.jpg)

![Fig. 43. Temporal series of X-ray diffraction patterns for a PS30/F18 pellet annealed in situ at 160°C in vacuum [20]. Reproduced from Vaia, Jandt, Kramer and Giannelis by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_044.jpg)

![Fig. 45. WAXD patterns for (HE)2M,R, organoclay and (HE),M,R, organoclay nanocomposites based on LMW, MMW, and HMW matrices containing ~ 1.5 wt% MMT [149]. Reproduced from Fornes, Yoon, Keskkula and Paul by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_045.jpg)

![Fig. 47. (a) Molecular structure and nomenclature of amine salts used to organically modify Na*-MMT by ion exchange. The symbols M: Methyl, T: Tallow, HT: hydrogenated tallow, HE: 2-hydroxy-ethyl, R: rapeseed, C: coco, and H: hydrogen designate the substitutents on the nitrogen. (b) Organoclays used to evaluate the effect of structural variations of the amine cations on nanocomposite morphology and properties [151]. Reproduced from Fornes, Yoon, Hunter, Keskkula and Paul by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. alternate for organically modified MMT. In this process, the Na*-MMT slurry was blended with melting N6 using an extruder, followed by removing the water. WAXD patterns and TEM observations clearly indicates the exfoliation of MMT layers in the N6 matrix but the final properties of N6/Na‘- MMT nanocomposites were nearly equal to those of Fig. 49 shows schematic figures depicting dis- persion of the Na‘-MMT silicate layers of the clay slurry into the N6 matrix during compounding by an extruder. According to this study, the exfoliation of silicate layers into the N6 matrix occurs as follows:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_046.jpg)

![Fig. 46. Bright field TEM images of melt compounded nanocomposites containing ~ 3 wt% MMT based on (a) HMW, (b) MMW, and (c) LMW N6 [149]. Reproduced from Fornes, Yoon, Keskkula and Paul by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_047.jpg)

![Fig. 48. Morphological analysis of nanocomposites based on HMW Nylon-6 and the organoclays M3(HT), and M2(HT)2-95. (a) WAXD patterns and TEM images of (b) M3(HT), and (c) M2(HT).-95 based nanocomposites. The concentration of mmt in the M3(HT), and M>(HT)2-95 nanocomposites are 2.9 and 3 wt% [151]. Reproduced from Fornes, Yoon, Hunter, Keskkula and Paul by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_048.jpg)

![Fig. 49. Schematic figures depicting dispersion of the Na‘-MMT slurry into nylon-6 during compounding [155]. Reproduced from Haegawa, Okamoto, Kato, Usuki and Sato by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_049.jpg)

![Fig. 51. Schematic representation of the dispersion process of the OMLS in the PP matrix with the aid of PP-MA [286]. Reproduced from Kawasumi, Hasegawa, Kato, Usuki and Okada by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_050.jpg)

![Fig. 53. WAXD patterns for OMLS, PP-g-MA, and various PPCNs. The dashed lines indicate the location of the silicate (001) reflection of OMLS. The asterisks indicate a remnant shoulder for PPCN2 or a small peak for PPCN4 [303]. Reproduced from Nam, Maiti, Okamoto, Kotaka, Hasegawa and Usuki by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. Fig. 52. Schematic illustration of OMLS dispersion process in PP-g-MA matrix [294]. Reproduced from Hasegawa, Okamoto, Kawasumi, Kato, Tsukigase and Usuki by permission of Wiley-VCH, Germany.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_051.jpg)

![Fig. 114. Shear viscosity as a function of time [391]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Okamoto and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_113.jpg)

![Fig. 55. The schematic illustration for dispersed clay structure and the inter-fibriller structure for PPCNs with: (a) 2 wt% and (b) 7.5 wt% MMT [303]. Reproduced from Nam, Maiti, Okamoto, Kotaka, Hasegawa and Usuki by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK. Very recently, EPDM/clay nanocomposites were prepared by mixing EPDM with OMLS via a vulcanization process [332]. They used thiuram and dithiocarbamate for the vulcanization accelerator. WAXD analysis and TEM observation revealed that the clay layers were exfoliated and almost dispersed as monolayers. Davis et al. [181] first reported the preparation of PET-based nanocomposite using this method. PET/MMT nanocomposites were com- pounded via melt blending in a co-rotating mini twin-screw extruder operated at 285°C using 1,2- dimethy]l-3-N-alkyl imidazolium salt modified MMT (hexadecyl-MMT) for the nanocomposite preparation. Table 7 summarizes the various conditions and](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_054.jpg)

![Fig. 57. TEM images of: (a) CD12 showing high levels of dispersion and exfoliation, average tactoids of four sheets per stack and (b) CD13 showing similar levels of dispersion and delamination as compared to CD12 [181]. Reproduced from Davis, Mathias, Gilman, Schiraldi, Shields, Trulove, Sutto and DeLong by permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc., USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_056.jpg)

![Fig. 58. (a) Chemical structure of liquid crystalline polymer, DHMS7, 9. (b) Schematic structure of OMLS [366]. Reproduced from Vaia and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_057.jpg)

![Sinha Ray et al. [374,375] first used this technique for the preparation of intercalated PLA/layered silicate nanocomposites. For nanocomposite (PLACNs) preparation, C18-MMT and PLA were first dry-mixed by shaking them in a bag. The mixture was then melt-extruded using a twin-screw extruder operating at 190°C to yield light gray strands of PLACNs. Nanocomposites loaded with a very small amount of o-PCL as a compatibilizer were also In another report, Chang et al. [368] prepared nanocomposites of thermotropic liquid crystalline Fig. 59. X-ray diffraction patterns of the 25 wt% DHMS7, 9-75 wt% M2C18 mixture (i) before annealing and (ii) after 100, (iii) 280, and (iv) 620 min anneal at 160 °C. Dotted lines indicate (00/) reflections of DHMS7, 9 intercalated M2C18 whereas arrows indicate original reflections of unintercalated M2C18 and DHMS7, 9 [366]. Reproduced from Vaia and Giannelis by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_058.jpg)

![Fig. 60. (a) WAXD patterns of C25A and C25A/TLCP nanocomposites. (b) Bright field TEM images of (a) 2 wt%, (b) 4 wt%, and (c) 6 wt% C25A in TLCP nanocomposites [368]. Reproduced from Chang, Seo and Hwang by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_059.jpg)

![Fig. 61. WAXD patterns for C18-MMT and various PLACNs: (a) without 0-PCL and (b) with o-PCL. The dashed line in each figure indicates the location of the silicate (001) reflection of C18-MMT. The asterisks indicate the (001) peak for C18-MMT dispersed in PLA matrices [374]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Maiti, Okamoto, Yamada and Ueda by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. Parts a and b of Fig. 63 represent the WAXD patterns of saponite organoclays with different the effect of varying the chain length of the alkylpho- sphonium modifier on the properties of organoclay, and how the various clays behave differently with the same organic modifier. They also studied the effects of dispersion, intercalation, and aspect ratio of the clay on the material properties. Table 11 gives the name,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_060.jpg)

![Fig. 62. TEM bright field images: (a) PLACN2 ( X 10,000), (b) PLACN4 ( x 10,000), (c) PLACN2 ( X 400,000), and (d) PLACN4 ( x 40,000). The dark entities are the cross-section of intercalated OMLS, and the bright areas are the matrices [374]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Maiti, Okamoto, Yamada and Ueda by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_061.jpg)

![Fig. 65. WAXD patterns of smectite-organoclay nanocomposites having different organic components (chain length dependency on intercalation). The broken lines represent the peak position of the corresponding organoclay [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_062.jpg)

![Fig. 63. WAXD patterns of organically modified clay: (a) smectite clay modified with Cg, Cj, and Cy¢ phosphonium salt; (b) smectite, MMT, and mica clay modified with C;_ phosphonium salt [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_063.jpg)

![4. Nanocomposite properties Fig. 64. Schematic representation of organoclays with Cj. ion [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. Very recently, Lee et al. [398] reported the preparation of biodegradable aliphatic polyester (APES)/organoclay nanocomposites using a melt intercalation method. Two kinds of organoclays, Cloisite 30B and Cloisite 10A, with different ammonium cations located in the silicate galleries, were chosen for the nanocomposite preparation. The WAXD analyses and TEM observations showed higher degrees of intercalation for APES/ Cloisite 30B nanocomposites as compared to that of APES/Cloisite 10A nanocomposites. It was hypothe- sized that this behavior may be due the stronger](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_064.jpg)

![Fig. 67. WAXD patterns of smectite, MMT, and mica nanocompo- sites with Cj organoclay and same clay content [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_065.jpg)

![Fig. 66. Bright filed TEM images of (a) PLACN12 (Cg, 1.7 wt%) and (b) PLACN2 (Cj6, 3 wt%) [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_066.jpg)

![Fig. 68. Schematic presentation of silicate layers in OMLS and in various nanocomposites [381]. Reproduced from Maiti, Yamada, Okamoto, Ueda and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_067.jpg)

![Fig. 72. Temperature dependence of G'’, G” and tan 6 for for PP-MA matrix and various PPCNs [303]. Reproduced from Nam, Maiti, Okamoto, Kotaka, Hasegawa and Usuki by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_070.jpg)

![Fig. 71. Temperature dependence of G’ and tan6 for the nanocomposites and corresponding copolymer/QA* blends without clay [68]. Reproduced from Okamoto, Morita, Kim, Kotaka and Tateyma by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_071.jpg)

![Fig. 74. Temperature dependence of G’, G” and tan 5 for N6 matrix and various N6CNs. PLACNs [374]. In order to understand the effect of compatibilizers on morphology and mechanical properties, the authors also prepared PLACNs with very small amount of oligo(e-caprolactone) (o0-PCL). The composition details and designations for various types of nanocomposites are presented in Table 8.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_072.jpg)

![Fig. 73. Dynamic mechanical spectra: (a) storage modulus, E’, (b) loss modulus, E”, and (c) loss factor tan 6 as a function of temperature fo neat PP and PPCN [304]. Reproduced from Liu and Wu by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd, UK.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_073.jpg)

![Fig. 75. Temperature dependence of G’, G” and their ratio tan 6 for PLACNs and the corresponding matrices: (a) without o-PCL and (b) with o-PCL [374]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Maiti, Okamoto, Yamada and Ueda by permission of American Chemical Society, USA. the matrix, indicating that C18-MMT has a strong effect on the elastic properties of neat PLA. Below T7,, the enhancement of G’ is clear for various intercalated PLACNs. On the other hand, all PLACNs show a greater increase in G’ at high temperature compared to Parts a and b of Fig. 75 show the temperature dependence of G’, G” and tan 6 of the PLA matrices and the various PLACNs, respectively. For all PLACNs, the enhancement of G’ can be seen over the investigated temperature range when compared to](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_074.jpg)

![Fig. 76. Temperature dependence of G’, G” and their ratio tan 6 for (a) PBSCNs (prepared with C18-MMT) and neat PBS, (b) PBSCNs [391]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Okamoto and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_075.jpg)

![From Fig. //, 1t 1s clearly observed that PBSCNs show a strong increase in G’ compared to other nanocomposites having the same clay content in the matrix. PPCNs are well known as intercalated systems, N6CNs are well-established exfoliated nanocomposites, PLACNs are considered interca- lated-and-flocculated nanocomposites, while PBSCNs are intercalated-and-extended flocculated nanocom- posites [391,392]. Due to the strong interaction between hydroxylated edge—edge groups, the clay particles are sometimes flocculated in the polymer matrix. As a result of this flocculation, the length of the clay particles increases enormously, resulting in a corresponding increase in overall aspect ratio. For the preparation of high molecular weight PBS, di- isocyanate end-groups are generally used as a chain extender [424]. These isocyanate end groups make urethane bonds with hydroxy-terminated LMW PBS. Each high molecular weight PBS chain contains two such bonds (see schematic illustration in Fig. 78). These urethane type bonds lead to the strong Fig. 78. Formation of urethane bonds in high molecular weight PBS [391]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Okamoto and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_078.jpg)

![Fig. 79. Formation of hydrogen bonds between PBS and clay, which leads to the flocculation of the dispersed silicate layers [391]. Reproduced from Sinha Ray, Okamoto and Okamoto by permission of American Chemical Society, USA.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/30475323/figure_079.jpg)