N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes of Copper, Nickel, and Cobalt

2019, Chemical Reviews

https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.CHEMREV.8B00505…

232 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

The emergence of N-heterocyclic carbenes as ligands across the Periodic Table had an impact on various aspects of the coordination, organometallic, and catalytic chemistry of the 3d metals, including Cu, Ni, and Co, both from the fundamental viewpoint but also in applications, including catalysis, photophysics, bioorganometallic chemistry, materials, etc. In this review, the emergence, development, and state of the art in these three areas are described in detail.

Figures (390)

![Scheme 2. Synthesis of Complexes [CuX(NHC)] Using Cu,O or CuX/K,CO, Table 2. Summary of Reaction Conditions to [CuCl(NHC) ] by the Cu,O or K,CO;/CuCl Methods](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_002.jpg)

![Table 1. Summary of Optimum Reaction Conditions to [CuX(NHC)] Using Free NHCs (SIMes)] included deprotonation with NaO¢Bu. The use of SIPr-HBF, should be avoided because it leads to products contaminated with [Cu(SIPr),]*. However, the source of the bulkier IAd is preferentially IAd-HBF, since formation of [Cu(IAd),]* is suppressed due to sterics, and in this case, deprotonation with KOMe in toluene gives the best results. Finally, the complexes [CuX(ICy)] and [CuX(ItBu)] were best prepared using this methodology by the reaction of isolated ICy and IfBu with CuX precursors. Ag transmetalation methodology is also generally applicable and in certain occasions leads to marginally improved yields. These results are summarized in Table 1. Although the methods outlined above lead to mononuclear complexes with SIPr and SIMes for X = Cl, Br, I, the structure of [Cul(IAd)] comprises a binuclear arrangement with two bridging iodides, and those of [CuX(ICy)] (X = Br, I) are hexanuclear and trinuclear, respectively, with unusual bridging ICy arrangements.” A detailed study of the nuclearities in solution as a function of the nature of solvent and polarity has not been undertaken. synthesis of silver NHC complexes from azolium salts and Ag,O).*’ The side product after the complexation is H,O; the selectivity to heteroleptic species and the easy workup are advantageous compared to Methods A and B. Another improved method for the synthesis of [CuX(NHC)] circum- venting the use of the unselective transformations with free NHCs involves deprotonation of the azolium salts by K,CO, in acetone at 60 °C. This method has initially been applied to the synthesis of Au-NHC complexes; it features inexpensive and easy-to-handle reagents and solvents and shows a good scope for the synthesis of substituted imidazol(in)-2-ylidenes, including the otherwise inaccessible [CuCl(SICy)] and [CuCl(IPr*)], which were previously obtained only via the Cu,O methodology under microwave conditions. Further- more, starting from CuBr or Cul, [CuBr(NHC)] and [Cul(NHC)] could be obtained in good yields;** interestingly, formation of homoleptic [Cu(NHC),]* was not observed with this method. Evidence was provided that the intermediates preceding deprotonation were azolium salts with [CuCIX]~ counterions. Finally, the preparation of SIMes and SIPr was also successfully carried out by the deprotonation of the corresponding azolium salts with aqueous or ethanolic ammonia in very good yields, although this methodology is not applicable to the less acidic imidazolium salts substituted by alkyl substituents [e.g (IAdH)*, (IfBuH)*].*°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_003.jpg)

![Scheme 4. Synthesis of Monodentate Cu-NHC Complexes with Bulky Rigid Ligands chloride using the Cu,O methodology in acetonitrile at 80 °C and microwave heating.” The same methodology under optimized conditions was also used for the synthesis of the mesoionic imidazol-4-ylidene complex 7“ (toluene 110 °C, 24 h) and the bis(diisopropylamino)cyclopropenylidene (BAC) complex [CuCl(BAC)] (8°) (MeCN, 2 h, microwave heating).’** Mononuclear complexes with the six- and seven- membered extended ring NHCs 9“ and 10“ were prepared by transmetalation of the ligand from analogous AgBr complexes (accessible from azolium bromides with Ag,O) to](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_003.jpg)

![The mononuclear complex [CuCl(M"*cAAC)] was initially prepared by simple association of the free M°"*cAAC with CuCl in THF.** More recently, an extended series of complexes including [CuX(“*cAAC)], [CuX(McAAC)], and [Cux(’cAAC)] (X = Cl, Br, I) (11%) (Scheme 6) has been prepared following similar methodology.’ The bromo and iodo analogues were best obtained, free from [Cu(cAAC),]* contaminants, by halide metathesis with NaBr and Nal from the chloro species, respectively (Scheme 6). All complexes show good therma (up to 200 °C/0.3 mmHg) and air stability (for several weeks). Lately, the Cu,O method was optimized (dioxane, 100 °C) to encompass one precursor to cAAC to giving the Cu c photophysical pro hloride complex 11b‘". The interesting perties exhibited by these complexes may](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_005.jpg)

![Scheme 10. Synthesis of Mononuclear Copper Fluorides Interestingly, the mononuclear complexes 21b™ and 21d“ are prone to the formation of the dinuclear species 23b™ and 23d“, respectively, featuring one single bridging j/,-fluoride. These transformations were brought about stoichiometrically by the reaction with [Cu(OTf£)(IPr)]® or triphenylmethyl carbenium tetrafluoroborate in THF (Scheme 12).°? The have a substantial ionic character (>65% of the bonding interactions) originating from the Coulomb attraction between the positively charged Cu atom and the o-electron pair of the C(NHC). The covalent part of the bonding shows little z- backbonding, which is comparable to a-backbonding in classical Fischer carbene complexes bearing two a donors on the carbene carbon.**”** The comparative study of the bonding in [CuCl(NHC)] [NHC = simplified “normal” imidazolyli- dene (bound from C2) and “abnormal” imidazolylidene (bound from C4)] showed also that the total strength of the Cu-C(NHC) bond depends on the orbital interactions and electrostatic attraction. The calculated bond dissociation energy trend, aNHC > NHC (C2-coordinated), was accounted for by the higher energy level of the o-lone-pair orbital in the abnormal NHCs, as well as the increased electrostatic attraction in this case.°°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_009.jpg)

![Scheme 13. Synthesis of Various [CuX(NHC)] Complexes (X = Anionic O Donor) IPr}] (25a"/ and 25b"“) with phenol or ethanol leads to phenoxides 278/89" 27a" and ethoxides 27e"/" and 27£', respectively, with release of CH, (route D); in all cases, the mononuclear nature of the products was established crystallographically.°”°* Preparative methodologies for com- plexes 25“ are discussed later (section 2.2.1.1.5 and Scheme 28). The mononuclear hydroxide [Cu(OH)(IPr)] (26%) is available in good yields from the reaction of [CuCl(IPr)] with CsOH in THF. It can participate in a range of heteroatom-H activation reactions under release of H,O (see below); with MeOH and tBuOH, 26% gives the corresponding alkoxides almost quantitatively (route B).° Following an alternative preparative strategy, the [Cu(OftBu)(NHC)] complexes were obtained by the reaction of the free NHCs with [Cu(OfBu) ], (route C). The method has a good scope with respect to the nature of the NHC for the synthesis of tert-butoxides.”°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_011.jpg)

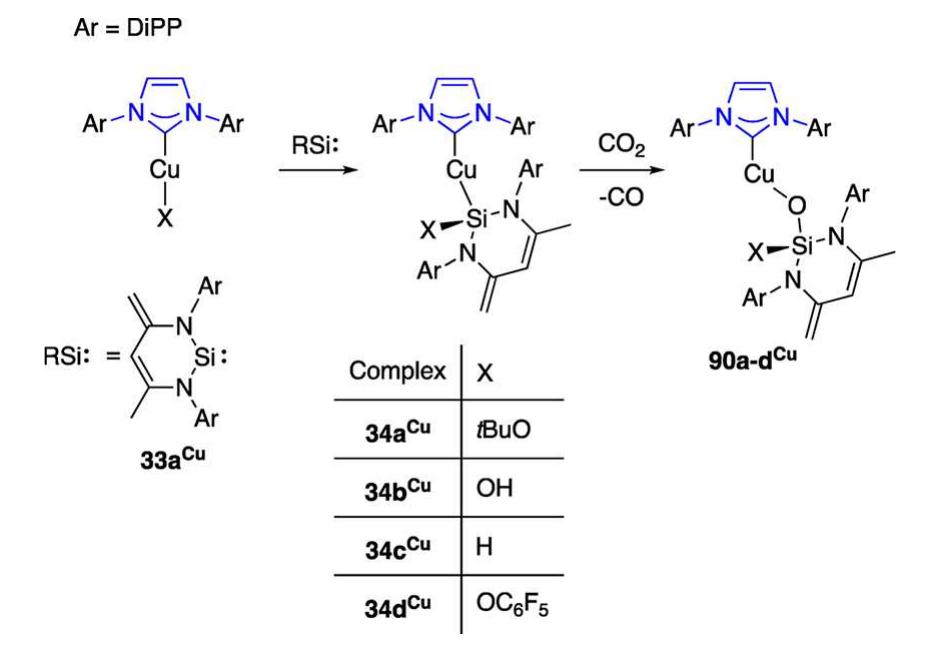

![27a"", opened new ways for the derivatization of two- coordinate Cu(NHC) centers with Cu-H, Cu-B, Cu-C, and Cu-Si reactive functionalities and subsequent applications in catalysis. The reactivity of 27a" is summarized in Scheme 15. Seminal work described the synthesis of the boryl complex 30a from 27a"*" and [B(pin)],; 30a catalyzed the reduction of CO, to CO with concomitant transfer of one oxygen atom of CO, to boron (see section 2.2.1.1.8, Reaction Involving Reduction of CO, to CO, for discussion).”* Reaction of 27a" with SiH(OEt), gave the dinuclear complex 31a" with symmetrical hydride bridges and limited stability in solution at ambient temperature (Cu-H at 6 = 2.67 ppm in C,D,); this, in combination with the high solubility of 31a" in nonpolar solvents, hampered its isolation in pure form and in good yields.°* Arylation or alkynylation of Cu in 27a"™ by the corresponding boronic esters BR(pin) (R = aryl, alkynyl) gave selectively the copper alkynyls and aryls 32a", 25h", and 25n"“, respectively,"°’*”° without competing formation of diorganocuprates. The insertion of silylene 33“ into the Cu-OfBu bond of 27a" gave the addition product 34a“; a family of related complexes was studied in the context of the effect of heteroatom-substituted anionic silyl group nucleo- philicity on the reduction of CO, to CO in well-defined complexes.’° Reaction of 27a" with tetrafluoro- or pentafluoro-benzene gave after C—H activation the fluoroaryl complexes of type 35“ and 36.”’ Reaction of 27a" with the simple silyl-boranes (pin)B-ER, (ER; = SiMe,Ph, SiPh;), or the stannyl-borane [(C,H,)(iPrN),]B—SnMe, (37°), gave the complexes [Cu(ER,)(IPr)] (38a%", 38b%) and 39a“, respectively (see also Scheme 37).’””* The silylation reactions using the silyl- and stannyl-boranes most likely involve o-bond metathesis and selectively produce silyl- or stannyl-complexes but only traces of boryl species. This has been attributed to the preferred quaternization of R,Si-B(pin) rather than pentacoor- dination at R,Si-B(pin) in the metathesis transition state.” The complexes 38a°" and 38b“ are convenient sources of nucleophilic silyl groups, for example in conjugate additions to unsaturated carbonyl compounds’ and other catalytic applications. The complex 27a" served as starting material for the synthesis of trifluoromethyl complexes; initial efforts using one equivalent of SiMe3;CF; as source of CF; led to the formation of 40“, which despite featuring the mononuclear two-coordinate Cu-CF, moiety, also showed remote function- alization of the [Pr ligand by SiMe, (see also section 2.2.1.1.5).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_012.jpg)

![Scheme 15. Diverse Reactivity of the Complex [Cu(OfBu)(NHC)] (27a"™) Mechanistic details on this process have not been estab- lished.*' Scheme 17. Diverse Reactivity of the Hydroxide Complex [Cu(OH)(IPr)] (26) Alkenes substituted with electron-withdrawing groups insert into the Cu-O bonds of Cu(IPr) alkoxides or phenoxides with anti-Markovnikow regioselectivity; these reactions are best described as nucleophilic additions of the coordinated alkoxides to the alkene.*’~** The aforementioned trans- formations have been extended to the catalytic intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of alkynes (Scheme 16).”*](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_013.jpg)

![reactions of a range of a@,f-unsaturated carbonyl substrates with [Cu(SiMe,Ph)(IPr)] proceeded to the formation of the O-bound enolate, except with a,f-unsaturated esters, where the C-bound regioisomer was obtained. A range of complexes were identified in solution by NMR techniques and in the solid state crystallographically.°° An O-bound enolate has been Cu(NHC)-enolates. There is a limited number of well- defined [Cu(enolate)(NHC)] complexes that have been postulated or isolated. They occur as intermediates in the (Cu-NHC)-catalyzed reaction of a,f-unsaturated carbonyl compounds (ketones, aldehydes, and esters) with the silyl borane B(pin)-SiMe,Ph which gives after _ hydrolysis p-silyl carbonyl/carboxyl species (Scheme 19).°° Stoichiometric](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_015.jpg)

![Scheme 18. Reactions of the Copper Hydroxide cAAC Complex 11e“ of [Cu(OfBu)(cAAC)] through reaction with NaOz¢Bu; protonolysis of the latter with a range of substituted phenols, anilines, and thiophenols provided a clean route to the respective phenoxides, anilides, and thiophenoxide (Scheme 18).*° All these complexes show good thermal stability and have been studied in the context of their photoluminescence properties. postulated in the reaction of [Cu{B(pin)}(IPr)] with trifluoromethylketones. In this case, in the /-B(pin)- substituted alkoxide formed by the insertion of the trifluoromethylketone into the Cu-B(pin), a /-F-B(pin) elimination provides the route to the reactive enolate formation, which nucleophilically adds to give a product of net C—F activation of the trifluoromethyl group of the ketone (Scheme 19).°” renee](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_016.jpg)

![have been used to prepare the two-coordinate air sensitive Cu anilides 57a“"—57c™ (Schemes 23 and 24) and the pyrrolide 58% by alkanolysis of | the analogous methyl and ethyl complexes (Scheme 23).°”°* Spectroscopic and computational studies evidence that there is no favored conformation of the phenylamido in 57a“"—57c™ even at —80 °C, which has been attributed to the absence of any Cu-N a-bonding (N to Cu(4p)). Surprisingly though, crystallographic studies reveal planar geometry around the anilido N atoms, which is commonly found in early transition metals featuring strong a-bonding. Computational studies suggest that this planarity may be due to electronic effects associated with the phenyl amido substituent rather than the Cu center. Conversely, the anilido ligand in 57a°"—57c™ is nucleophilic and reacts with Et-Br, leading to alkylation of the anilines and concomitant formation of [CuBr(NHC)] (Scheme 24). The reactivity toward the nucleophile follows the order §7c“ > 57b“ > 57a‘ and was ascribed to steric factors.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_018.jpg)

![Na*(PCO)7), has displayed limited coordination chemistry with transition meta s due to its strong reducing power.’ However, reaction of Na(PCO) with [CuCl(cAAC)] (11d“) gave the complex 66°", featuring a 77-(KC,KP)- phosphaethynolate igand. The 31p NMR signal of the coordinated PCO at 6 = —387 ppm is slightly downfield shifted compared to Na(OCP) (6 = —392 ppm), giving evidence of minor e ectronic reorganization of the ligand on coordination. Interestingly, 66“ reacts further with cAAC, giving the salt 67 containing the cationic homoleptic species [Cu(cAAC),]* and (PCO)~ as counteranion; the latter does not show any close contact with cationic or solvent sites in the lattice. This feature may persist in solution as evidenced by the upfield shift of the anion signal (6 = —400 ppm) in the *!P NMR spectrum (Scheme 26)./°*](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_022.jpg)

![the following discussion, the C-donor anionic complexes are classified according to the hybridization type of the C donor atom (in the order sp®, sp”, and sp) and the method used for the Cu-C bond formation; (per)fluorocarbyls are grouped separately. and gave a mixture of alkylated and arylated Cu(IPr) products (ca. 8:1 ratio), separable by fractional crystallization."°° The complexes 25e"“ and 25c"“ have also been prepared by using [CuCl(ICy)] or [CuC 7 10 agents, respectively. 7,1 (IPr)] and MeLi or EtLi as alkylating os Finally, [Cu(7'-allyl)(IPr)] (25f") was prepared by transmetalation from Si(allyl)(OMe), to the Cu in [CuF(IPr method of wider ] fo lowing SiF(OMe), elimination, in a scope.’ Heating of the methyl complexes 25a"/S“ and 25b'/S™ at temperatures between 100 and 130 °C in CgD¢ produced met hane, ethane, and ethylene, in addition to a black precipitate or pink plating and other unidentified Cu(NHC) complexes but not free NHCs or imidazolium salts. When the thermo ysis was performed in the presence of radical traps (TEMPO and cyclohexadiene), no change was observed concerning the course of the reaction, thus eliminating the possibility of homolytic decomposition paths.°° Interestingly, oxidation of the complexes 25a"/“ or 25c"/S™ with AgOTF to [CuX(NHC)] (X = anionic C donor with sp*-hybridized atom). The first alkyl complex [CuMe(IPr)] (25a"") was prepared in good yields by the reaction of [Cu(OAc)(IPr)] with AlMe,(OEt).°’ The methodology was extended to SIPr and (S)IMes analogues using the same Cu starting material and AlMe; or AIEt, alkylating agents a" In work that was aimed to elucidate the mechanism of tandem catalytic C— H activation and carboxylation of substituted aromatics with [Al(iBu)3(TMP)]Li/CO, (TMP = tetramethylpiperidine) (see below section 2.2.1.1.8, Reactions Involving Hydro- cuparation of Alkynes), [Cu(O¢Bu)(IPr)] was reacted stoichiometrically with Li[Al(iBu)3(anis)] (anis = 2-anisyl) Scheme 27. Synthesis of Alkyl and Allyl NHC Copper Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_023.jpg)

serving as a Cu* source with labile ligands, amenable to the formation of j-(o,a-acetylide) dinuclear complexes, resulted in markedly accelerated reaction leading to the complex 72b“ with the coordinated triazolide, which is analogous to 72a“. This, in combination with the observed scrambling of isotopically labeled Cu reactant complexes, was interpreted as evidence of involvement of . “eos ; oil binuclear sites in the catalytic transformation.’ '* addition product is bridging two distinct Cu(cAAC) termini, one bound through a Cu-Csp” and the other through a dative Cu-N bond to the aromatic triazolyl ring. The catalytic competence of the 73“ and 74“ over the mononuclear acetylide 32b“" was demonstrated by the favorable conversion kinetics to products when used in the presence of suitable substrates. Importantly, the weakly coordinating OTf was crucial for the successful isolation of 74“, always maintaining coordinatively unsaturated Cu centers. Complex 74“ served as a catalyst resting state that can be converted to 32b“ by the action of phenylacetylene via the alkanolysis of the Cu-C(sp?- triazolyl) bond (Scheme 30).''°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_025.jpg)

![Scheme 32. Syntheses of [Cu(alkynyl)(NHC)] Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_026.jpg)

![electrophilic SiMe; group of the reagent (see also Scheme 15). Use of saturated NHC instead of IPr led to clean substitution of the tBuO by CF; and the isolation of the mononuclear 77a— cS"?! The complex 77b™ has been shown to be involved in a redistribution equilibrium in THF (K,,"" ca. 1.2) leading to the formation of the ion pair 78b~™ with homoleptic [Cu(SIMes),]* cation and [Cu(CF;),]7 anion.'”” The](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_028.jpg)

![a product of the nucleophilic attack of the coordinated fluoroaryl to the electrophilic N reagent (Scheme 34). energetics of the redistribution have not been detailed, and the transformation has not been described with other analogues of 78b“. By a similar methodology, the [Cu(CHF,)(NHC)] complexes 79"/S“" have been obtained (Scheme 33).'~* Interestingly, in this case the CHF, analogues of 77a“ and 77b“", were not formed in appreciable quantities, and equilibria involving ion-pairs were not observed. This may be related to the different steric requirements of the two fluoroalkyls. An alternative approach based on the availability of the “ligand-free” CuC,F; (obtained by cupration of C,HF; with [K(DMF) ][Cu(O¢Bu),]) was employed for the synthesis of [Cu(C,F;)(IPr*)] (80). The reaction with the isolated IPr* provided the product (Scheme a3)" A. comparison of the oxidation potential of the organometallic complexes 77¢™ and 25a‘ bearing trifluoromethyl- and methyl-bound Cu centers, respectively, revealed that substitution of methyl for trifluoromethyl raised the potential by approximately +0.6 V versus ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc*) couple, as expected due to the high electron-withdrawing properties of the trifluoromethyl ligand.'*" Scheme 34. Synthesis of Fluoroaryl NHC Copper Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_029.jpg)

![Scheme 35. Model Reaction for the Catalytic Defluoro- Borylation of Fluoroalkenes and reactions were used as models for the mechanistic understanding of the corresponding successful catalytic systems. Complex 84“" was obtained by the borylative cleavage of one F—C vinylic bond via a fluoroalkene 1,2-addition-f elimination mechanism, starting from the weakly nucleophilic Cu-B(pin) complex 30°", and proceeded by the postulated 83“ addition adduct of boryl-cupration. Two distinct addition regioselectivities applicable to C,F, and gem-difluoro-alkene substrates, respectively, promote elimination of either B(pin)F or [CuF(IPr)] to give products of vic- or gem-defluoro- borylation 85a" and 85b“", respectively. The initially formed](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_030.jpg)

![moieties using silyl boranes. The initial attempts to prepare [Cu(SiPh,)(IPr)] consisted of reaction of [CuCl(IPr)] with KSiPh, in THF; KSiPh, was generated in situ from (SiPh,), and 2 equiv of K.'** The salt metathesis methodology introduced the mononuclear [Cu(SiPh3)(IPr)] and gave evidence for the nucleophilicity of the coordinated SiPh, through reactivity studies with CO, (see section 2.2.1.1.8, Reaction Involving Reduction of CO, to CO); the salt metathesis methodology was used again much later for the synthesis of a series of Cu-NHC complexes with bulkier silyl groups -Si(SiMe,),R (R = SiMe;, Et, 88a°"—88c“") (Scheme 36) and a range of NHC ligands differing in bulk.!”? Following the transmetalation methodology, the [Cu(SiPh;)(IPr)] obtained featured a mononuclear two-coordinate Cu center, but it was shown that decreasing the steric demands of the NHC, as when going from 88a" to 88d“, resulted in the formation of binuclear species with bridging silyl groups and cuprophilic interactions. All complexes described showed good thermal stability under inert atmosphere; in fact, 88a"—88cC were volatile under vacuum without decomposition and studied as volatile Seeman precursors for the deposition of Cu (Scheme 36). m1é6+1sds i a ee”: 1 a" Me fluorovinylboranes of type 85a" and 8Sb“ were converted to borate salts through the action of excess of KHF, and the latter isolated.'** This elegant method opens ways to access rare fluorovinyl-substituted derivatives (Scheme 35).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_031.jpg)

![the latter transformation is mechanistically vague (Scheme 40)" offer. Thus, the reaction of 27a"~" with SiH(OEt), gave the complex 31a" of limited stability in solution and the solid state at ambient temperature but isolable as yellow solid (Scheme 41). Its structural characterization at lower temper- atures by X-ray diffraction revealed a binuclear arrangement in the solid state, with inferred but not experimentally located and refined bridging hydrides. Supporting spectroscopic evidence for the presence of hydrides was gained by IR spectroscopy [v(Cu-H) absorption at 881 cm™!, shifted to 638 cm™! for v(Cu-D)], by 'H NMR spectroscopy [Cu-H at 6 2.67 ppm (s)], and by reactivity studies, mainly the hydrocupration of alkynes. Analogous stability was found for 31a°“" generated from CuF by reaction with a Si-H moiety (Cu-H at 6 1.93 ppm).'?® Increasing the size of the NHC ligand using IPent and IHept resulted in the complexes 31b® and 31c“, respectively, the former being the most stable in the series 31a“"—31c™, although quantitative stability data as well as the decomposition mechanism are not established.°? Computa- Scheme 40. Synthesis and Reactivity of Cu-Gallyl Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_035.jpg)

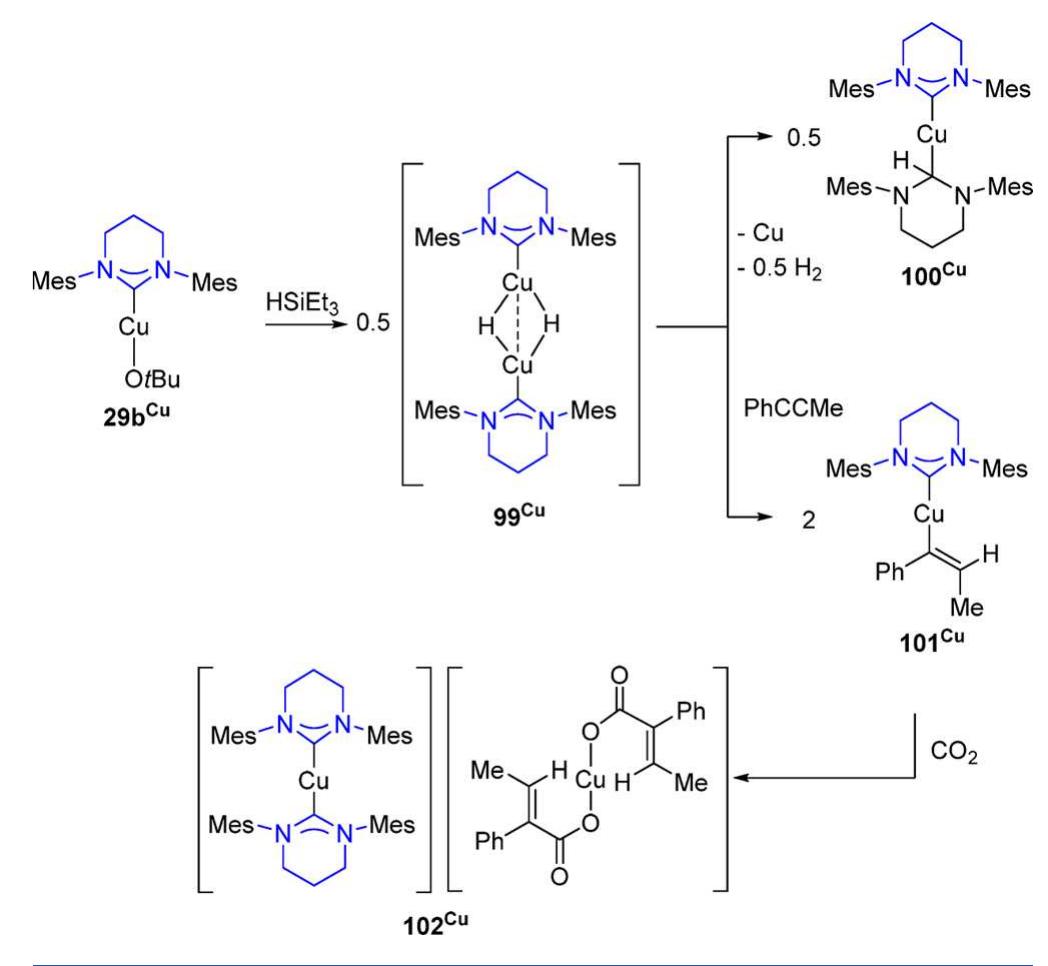

![Scheme 47. Formation of Cu-H-B Complexes With cAAC Ligands these cases, the relevant thermodynamic parameters to be considered in the postulated mononuclear intermediate precursors are the energies of [H-BEt,;]~ and [H-BH,]~ bonds and the energies of dimerization of a species [CuH(NHC)] succeeding H—B cleavage and leading to 94% and 99°. The computed values for the energies of [H-BEt,]~ are rather small, leading to facile H—B cleavage and formation of 94 thanks to favorable dimerization energetics; 103“ is observed due to the unfavorable dimerization energies. [H- BH,]~ and [H—B(C,F;),]~ are strongly bound fragments and permit the isolation of 104% and 105“.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_043.jpg)

![(IPr)] and two o-bond metathesis transition states, as shown in Scheme $1.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_044.jpg)

![Hydrosilylation and Hydroboration of CO . The hydro- silylation of CO, by SiH(OEt), is very efficiently catalyzed under mild conditions by [Cu(OfBu) (IPr)] (TOF = 1250 h7t, TON = 7590).'*° The proposed mechanism involves insertion of CO, into the Cu-H bond giving the x'-formate complex 111% followed by o-bond metathesis between this and SiH(OEt); to release the product and regenerate Cu-H; in stoichiometric reactivity studies 111°" was isolated, fully characterized and proved to be catalytically competent (Scheme 52). DFT calculations of the reaction in conjunction](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_045.jpg)

![Reaction Involving Hydrocupration of Alkynes: Overview. The involvement of alkynes as addenda to hydrocupration intermediates stabilized by NHC ligands has led recently to the development of versatile catalytic transformations. Although the details of the generation of the Cu(NHC)-H species under catalytic conditions vary and are of crucial importance for the overall activity and selectivity, in the majority of the cases, Cu-H reactive species are formed by the reaction of Cu’ alkoxides (occasionally of phenoxides or fluorides) with hydridic sources. In a few cases, stoichiometric reactions under controlled conditions have successfully been used to pin down or isolate intermediate complexes that were The reduction of alkyl triflates and iodides by a [Cu(OrBu)- (IPr)]-catalyzed protocol with reductant TMDSO and stoichiometric quantity of CsF was also postulated to involve [CuH(IPr)] and nucleophilic substitution of the triflate or iodide groups by hydride; radical pathways were minor and relevant only in the reduction of iodides (Scheme 54).'**](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_050.jpg)

![Scheme 56. Semireduction of Terminal or Internal Alkynes [CuH(©"IPr)] and its conversion to the o-vinyl complex by reaction with PhC=CtBu; the former could be isolated and proved to be catalytically competent.'””](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_052.jpg)

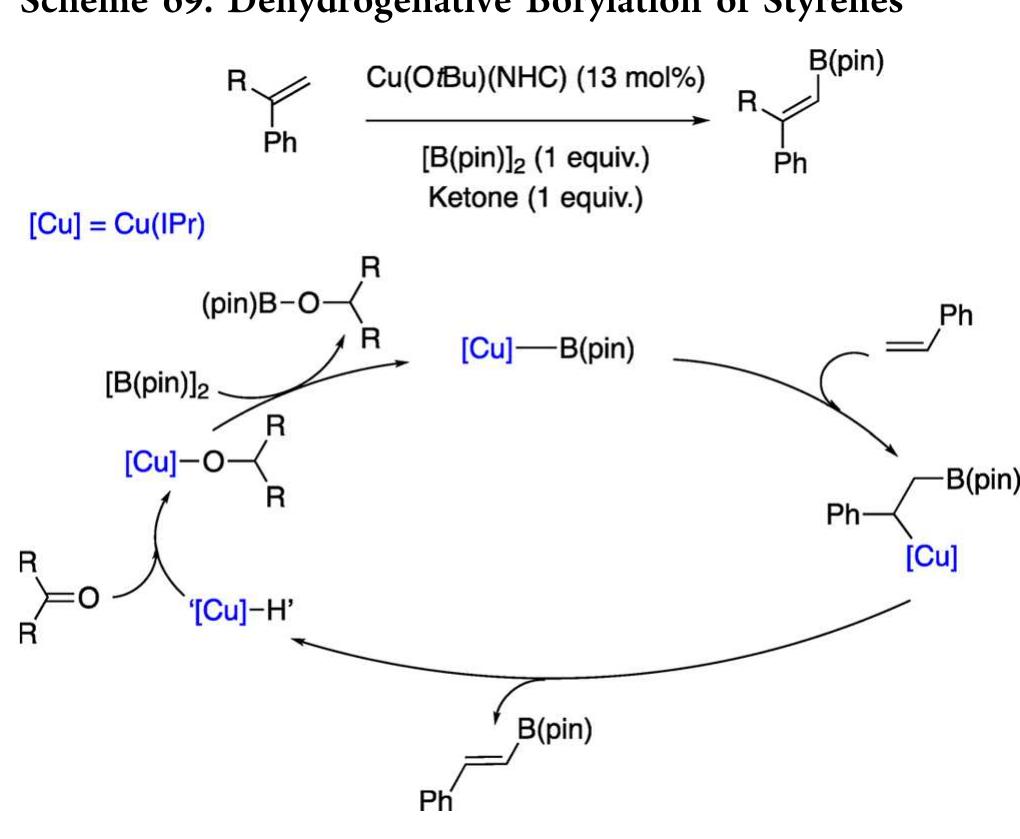

![in t syst Ph- in t the or aOtBu), [B(pin)],, and alkene (e.g., substituted styrene, etc.) he presence of Ph-Br and catalytic [Pd(OAc),]/phosphine ems, resulted in the cross-coupling of the /-borylalkyl with Br. The intermediacy of (NHC)Cu-/-borylalkyl originating he “Cu-cycle” and the requirement for Pd/phosphine for activation of the Ph-Br (“Pd-cycle”), that are both essential the transformation, were consolidated by resorting to the study of stoichiometric reactions. Optimization, scope, and selectivity of the catalytic system, which comprises two coo perating catalytic cycles working in tandem have been described (Scheme 68).'7!~'7%](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_061.jpg)

![work: an analogous interaction of CO, with [Cu(NHC)- B(OR),] prior to insertion was not found in [Cu(NHC)-Ar] due to the superior o-donor character and nucleophilicity of the B(OR), compared to o-aryl.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_064.jpg)

![Scheme 75. Stoichiometric Reduction of CO, to CO with the Silyl Complex 38b™ Finally, the reaction of [Cu(SnPh,)(IPr)] with CO, produces SnPh, and the benzoate complex [Cu{x-OC(O)- Ph}(IPr)] as the sole Cu-containing species in high yield in a transformation that involves Sn-Ph bond cleavage.”* DFT calculations were carried out to rationalize the nature of products obtained and the reactivity trends in the interaction of CO, with the complexes [Cu(EPh,)(NHC)] (E = Si, Ge,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_068.jpg)

![Scheme 78. Complexes of the Type [Cu(monodentate-NHC)L]* (L # NHC)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_070.jpg)

precursors (126a°"—126e™ Scheme 82). The complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_072.jpg)

![“The azide tagged and heteroatom functionalized imidazol(in)-2-ylidene complexes give signals i in. ca, 6 178 ppm and ca. 8 201 ppm, Aeapectively, in agreement with the parent complexes; in complex 3°", the Cyyc appears at ca. 6 212 ppm. In CD,Cl. “In CDCl. “Acetone-d°. “In C,D¢. Table 4. 6Cyyc in the C-NMR Spectra of Selected Complexes [CuX(NHC)] (NHC = Imidazol(in)ylidene, X = F, Cl, I)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_016.jpg)

![Table 5. 6 Cyyc in the '*C-NMR Spectra of the Complexes [CuX(NHC)] (NHC = ®®cAAC, RE-NHCs, BAC, aNHC, 1,2,3- triazol; X = Cl, Br, I)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_017.jpg)

![Table 8. 6Cyyc in the C-NMR Spectra of Selected [CuX(NHC)] and [Cu(NHC)L]X (L = Group 15 Donors Table 9. 5Cyyc in the '*C-NMR Spectra of Selected [CuX(NHC)] (X = Group 14 Donor) and of [Cu(IPr*)(CPh,) ]*](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_019.jpg)

![Table 7. 6Cyyjc in the C-NMR Spectra of Selected Complexes [CuX(NHC)] (X = SR, SH)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_021.jpg)

![Table 10. 6Cyyc in the 3C-NMR Spectra of [Cu(NHC),]*(A_) Salts Table 11. 6Cyyyc in the C-NMR Spectra of the Complexes [CuX(NHC)] (X = Group 13 Donor)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_022.jpg)

![ligands as tunable chromophores through modifications of the associated singlet—triplet gap was tested. In the [Cu(NHC)- (LX)] complexes, the symmetric di-(2-pyridyl)dimethylborate LX chelate possesses high energy triplet and acts as an ancillary ligand (Scheme g1)."](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_023.jpg)

![dehydrogenation of BH3-NH; in acetone/water mixtures, releasing 2.6 mol of H, per mole BH3-NH; with estimated TOF of ca. 3100 mol H, mol cat™’ h7!. Substitution of [CuCl(**cAAC)] by 148“ increased TOF to ca. 8400, while showing good catalyst recyclability. The activity of 148“ in the dehydrogenation reaction matches the one of noble metal catalysts,“](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_085.jpg)

![Scheme 100. Complexes with Oxazoline-Functionalized NHC Ligands 2.2.3.2. [CuX,(Lig)], [Cu(Lig)L,J", [CuX(Lig),J", and Relatea (Lig = Neutral Bidentate Heteroatom Functionalized NHC Ligand). A rare family of pyridine-functionalized NHC complexes of Cu" in a range of coordination numbers and geometries has been studied.” ° They were prepared by transmetalation from the silver complexes to CuBr, (Scheme 101). The nature of the isolated complexes depended on the mole ratio of NHC to CuBr, the substituents of the pyridine functionality, and the presence (during crystallization) of additional donors. The products obtained with ligand-to-metal ratio of 1:1 can be dinuclear (for unsubstituted pyridine) or mononuclear (for Y = Me or OMe), adopting distorted trigonal bipyramidal or tetrahedral geometries, respectively. The complexes with ligand-to-metal ratio of 2:1 are trigonal bipyramidal cationic species with trans-disposition of the NHCs. The Cu-Cyyc bond distances are rather long (1.95— 2.00 A). The remarkable stabilization of the Cu" centers under NHC ligation has been attributed to the pyridine functionality in a rigid structure, which hampers NHC dissociation. Hard— soft interactions between Cu" and Cyyc have been invoked to explain the relative scarcity of Cu'-NHC complexes, in particular with monodentate NHCs.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_091.jpg)

![2.2.4.2. [Cu(Lig)], [CuX(Lig)] (Lig = Anionic Tridentate Heteroatom-Functionalized NHC Ligand). The mononuclear Cu’ and Cu" complexes 178“ and 179% with the monoanionic rigid carbazolide pincer ligand bearing o-/z- donating amido bridgehead and mesoionic 1,2,3-triazol-S- ylidene wingtips were prepared by salt metathesis of the K* salt of the fully deprotonated bis(1,2,3-triazol-S-ylidene carbazolide 177 with Cul or CuCl, respectively. The ligan precursors were obtained by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition betwee the 1,3-diaza-2-azoniaallene salt and a 1,8-diethynylcarbazo and deprotonated using excess of KN(SiMe3), to th potassium complex 177“.°”> Attempts to obtain a Cu!- complex by the reaction of 179 with LiHBEt, led to 178° instead (Scheme 109). at 5 o o c=]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_098.jpg)

![Scheme 112. Complexes with Symmetrical [Cu,(#-X),] Bridges Scheme 113. Bi- and Tri-Nuclear Complexes Obtained with the Ligand RE-6-Mes(DAC)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_103.jpg)

![there is evidence that exchange of RE-6-Mes(DAC) takes place to form complexes of higher nuclearity. The complex [Cu{RE- 6-Mes(DAC)},]PFs was obtained by reaction of [Cu- (NCMe),]PE, with RE-6-Mes(DAC) as described above.”’* respectively (Scheme 114). The binuclear 186a“" features a bent structure (Cu-O-Cu = 127.8°) and short Cu-Cyyjc bonds (1.87 A). It has been used as a catalyst in the Cu-catalyzed AAC of benzyl azide with substituted phenylacetylenes in the presence of 4,7-dichloro-1,10-phenanthroline; it showed enhanced catalytic efficiency compared to [CuCl(IPr)] or [Cu(O¢Bu)(IPr)], a fact that was attributed to the absence of coordinating halides or other strongly bound ligands.””” respectively (Scheme 114). The binuclear 186a%" features a](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_106.jpg)

![“In C.D, Dinuclear. “Equilibrium mixture of mononuclear and dinuclear species, with the signal at 6 192.8 ppm assigned to the binuclear; for [CuH(S)IPr],, no “C NMR data were reported, presumably due to thermal instability.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_025.jpg)

![adopts a C;-symmetrical arrangement with two SIMes ligands coordinated to distorted trigonal-planar Cu' centers that are linked by the dianionic oxalato bridge in a p-1,2,3,4 coordination mode. Thermal decomposition of the complex occurs in the range 210—350 °C and cleanly converts the complex to Cu° with release of CO,.'” Reaction of 2 equiv [Cu(Mes)(SIMes)] with oxalic acid in THE gave the binuclear complex 202% (Scheme 122). It](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_114.jpg)

![The polymeric Cu complex 204% with the two-atom bridging anionic 1,2,3-triazole-4,5-diylidene has been prepared in two steps, involving complexation of CuX (X = Cl, I) with the mesoionic 1,2,3-triazol-ylidene, followed by deprotonation with KN(SiMe;)5. The complex was characterized by mass spectroscopy and further reactivity by transmetalation from Cu, yielding a range of mononuclear dimetalated complexes with Platinum Group Metals (Scheme 125).””” Binuclear complexes with 1,3-dimetalated bridging triazolide and [(cAAC)Cu-o-(u—1’ alkynyl-Cu)] complexes have been isolated as intermediates in the CuAAC of azides and alkynes (Schemes 30 and 124).'!®](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_115.jpg)

![Reaction of [CuCl(NHC)] (NHC = IMes, IXyl) with Na(NCS) gave the centrosymmetric binuclear complexes 203 with 1,3 bridging thiocyanate ligands; with the bulkier IPr, mononuclear complexes were obtained (Scheme 123).7**](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_116.jpg)

![steric repulsion of the NHC wingtips (Scheme 141). The complexes 221a°"—221e“ with smaller NHC wingtip R comprise two Cul centers bridged by two ligands arranged in a head-to-tail manner, rendering each copper coordinated by one phenanthroline and one NHC of the second ligand. The bond distances of Cu-C bond are ca. 1.88 A and the separation between the Cu ca. is 2.71 A, implying weak metal—metal interaction. In 221“, with the bulkier NHC wingtip DiPP, the two ligands are arranged in head-to-head manner, which may be due to reduction of steric congestion. In the complexes 221a—221e™, interconversion between head-to-head and head-to-tail arrangements is possible in solution as concluded by NMR spectroscopy. Use of imidazolium salts with halide counterions leads to complexes 222a“" with one bridging halide between the two Cu centers (Scheme 141).°”” Scheme 141. Binuclear Complexes with Phenanthroline Functionalized NHC Ligands available in a “one-pot” by the reaction of the C2-substituted imidazolium precursor 220a“" in the presence of CuCl; this transformation involves fast migration of the PPh, group, from the C2 to C4 remote position, accompanying complexation. Finally, the homodinuclear Cu’ complex 220d“ was easily accessible from 220b™ and CuCl. Heterometallic complexes can be obtained by substituting CuCl in the last step with other metal precursors (eg, [AuCl(SMe,)], [Pd(allyl) (u- Cl)],, etc.) (Scheme 140).°°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_131.jpg)

![Homometallic binuclear and trinuclear complexes with Cu’ centers are accessible by the use of the rigid mixed donor bis- diphosphanyl-NHC. The trinuclear 234a“" (D,,,), obtained by the reaction of the free NHC ligand with [Cu(OTf)], comprised a symmetrical ligand arrangement leading to three homoleptic Cu centers with one all-NHC and two all-P donations; the binuclear 234b (C,) obtained by the reaction of the imidazolium proligand with [CuN(SiMe;),] comprised two heteroleptic C centers and dangling phos- phines; an unusual bridging triflate mode was found in the structure of 234a“". The Cu--Cu separation in the latter is short (ca. 2.58 A) and shorter than the corresponding one in 234b™ (2.68 A). The geometries at Cu are almost linear (171-172°), and the orientation of the lone pairs of the dangling P donors in 234b“ is toward the metal. The NHC rings and the coordinated Cu centers are coplanar; there are some dynamic processes taking part in solution that render the NMR spectrum at room temperature rather broad (Scheme 147)318](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_134.jpg)

![end maintaining a positively charged electrophilic character and the other metal a nucleophilic character. Out of the three highest filled MO’s, one possesses Cu-M o-character and the other two Cu-M z*-character. Despite the differences in the nucleophilicities and reduction potentials of the various M fragments, the calculated Cu atomic charges were found invariant within the series. Complex 245a“" catalyzes the dehydrogenative borylation of unactivated arenes under photochemical conditions. The proposed mechanism postu- lates reaction of the bimetallic complex with the BH(pin) resulting in fission of the Cu-Fe bond to generate [CpFe- (CO),{B(pin)}] and [CuH(IPr)]; the former under photo- lytic conditions is the active borylating catalytic component of the arene. Recombination of [CuH(IPr)] and [CpFe(CO),H] affords the original bimetallic complex and H,, completing the catalytic cycle.” ie =a oe 1 ee ik. Pe fr](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_146.jpg)

![Scheme 156. Cylinder-Type Trinuclear Complexes 244a,b™ [Cu(OTf)(IPr)] (Scheme 158). Its structure displays a short Pd-Cu distance (2.55 A) and a strong interaction between Cu Scheme 157. Complexes with Direct Cu-M Bonds](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_148.jpg)

![led after long reaction times (ca. 2 weeks) to the binuclear products 2“! and 3%/, depending on the presence or not of adventitious silicone grease contaminants, respectively. Shorter reaction times (ca. 5 days) afforded low yields of the unstable three-coordinate [Ni(IfBu)(7’-1,3-COD),] (4%'), which con- verted to complex 5“ by C-—H activation of the fBu substituents. The mechanism postulated for the trans- formations involving IfBu is shown in Scheme 162, although the exact nature of the steps was not clarified.**”](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_152.jpg)

![Scheme 164. Homoleptic [Ni°(NHC),] by Substitution / Reduction of Ni! Precursors The diamagnetic [Ni(“’cAAC),] complex 8™! was obtained by reduction of [NiCl,(cAAC),] with LiNiPr, or KC, in THF.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_153.jpg)

![The purple, closed-shell, diamagnetic [Ni(RE-6-Mes),] (7b™') was obtained by the reduction of the Ni’ complex 7a! with KC, in THE (see also below sec 3.2.2.1.1).°*° The electronic structure of 7b“ comprises a frontier orbital region with five occupied metal-based orbitals with approximate 2:1:2 splitting: the near-degenerate HOMO set (with Ni d,, and d,, character) lying above a single o-type orbital (with Ni d, character) and further below is found a degenerate set (with Ni diy) and d,, characters) (Scheme 164).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_154.jpg)

![Scheme 166. [Ni(NHC)(77-Imine)] by Substitution at [Ni(1,5-COD),] 3.2.1.1.3. Heteroleptic [Ni(NHC)L,]. The reaction of [Ni- (CO),] with the sterically demanding ligands [Ad or ItBu led to the three-coordinate substitution products [ (CO),] (NHC = IAd, ItBu 12a™! and 12b™') after d i(NHC)- issociation of two CO ligands from [Ni(CO),]; 12a“! and 12b™' adopt distorted trigonal structures, with Ni-Cyyjc bond d ca. 1.95 A. Interestingly, monitoring the reactivity 0 12b™ under a CO atmosphere by IR spectroscopy ( not establish any associative CO reactivity to [ istances at f 12a" and 1 atm) did i(NHC)- (CO)3] species, which are commonly found with smaller NHCs; instead, direct conversion to [Ni(CO),] was observed, in a reaction that is the reverse of the preparation of 12a“! and 12b\. These observations corroborate the thermodynamic instability of [Ni(NHC)(CO),] (NHC = IAd, ItBu) (Scheme 167). The extraction of the thermodynamic parameters AH](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_155.jpg)

![Scheme 171. Reactivity of [Ni(NHC)(7’-styrene),] with Isocyanate and Thiocyanate](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_158.jpg)

![in the IR spectrum also corroborates a linear NO. Similar conclusions can be drawn for 19a“! based on spectroscopic analogies. Substitution of the iodide by SCPh, using TISCPh, maintains the same structural features of the Ni(NHC)(NO) moiety.°°* Reaction of 19b™ with NaCp led to the complex 19d™ with 4°-Cp coordination and bent NO to accommodate for the electron-rich metal, formally Ni". Reduction of 19a“! with Na/Hg provided binuclear Ni! complexes with bridging iodide and NO, while attempts to form the two-coordinate [Ni(IPr)(NO)]* led to the rearranged trigonal planar species 19f%', the cation of which comprises one “normally” and one “abnormally” coordinated NHCs; here too the coordinated O is linear as evidenced by crystallography and spectroscopy. Thus, despite the strong donor properties and favorable sterics of the IPr, the mononuclear [Ni(IPr)(NO)]* is too reactive to be isolated. ie te ee a es mein ini’ | lo a es](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_162.jpg)

![Scheme 175. Reactivity of Heteroleptic [Ni(NHC)(PPh;), ] Scheme 176. Transformations with [Ni(NO)X(NHC)]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_163.jpg)

![The reaction of 9“ or 10“! with diphenyl acetylene (1:1 ratio per Ni) gave the three-coordinate complexes 21™' with distorted trigonal planar geometry (assuming that the acetylene occupies one coordination site). '*C NMR spectros- copy gives evidence for departure from sp-hybridization of the 7’-alkyne C atoms, indicative of z-backdonation from the Ni to the alkyne. This is also confirmed from the solid state structure which reveals alkyne bond elongation and deviation from linearity; the alkyne vector lies in the coordination plane (Scheme 178).**” prepared by the reaction of [Ni(IMes),], formed in situ from [Ni(1,5-COD),] and [Mes in THF, with alkene after changing the solvent from THF to toluene. Complex 20a™' is stable in solution at room temperature and displays NMR spectra in accord with C, molecular symmetry originating from the interaction of the NHCs with the alkene CO,Me substituents. The symmetry is maintained in the solid state where the Ni adopts a trigonal planar coordination geometry with Ni-Cyyjc distances at ca. 1.95 A and elongated olefinic C-C distances (ca. 1.45 A), indicative of Ni-to-alkene z- backbonding. Studies of the speciation in the system Ni(IMes),/dimethyl-fumarate, as a function of the ratio of the added reactants, showed that with equimolar amounts in benzene at room temperature, 20a“! was formed; with two equivalents of alkene, the initially formed species are dinuclear (with Ni/alkene ratio of 1:1), the most stable of which, 20b‘, was structurally characterized. Finally, with three equivalents of alkene, the complex 13a“! was obtained (Scheme 177).°°°](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_164.jpg)

![equivalent of NHC, led to the rare three-coordinate, 16- valence-electron complex [Ni(NHC),(silylene)] (36)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_166.jpg)

![Scheme 179. System [Ni(CO),] with cAAC Scheme 180. Formation of Disilene and Distannylene Complexes (Scheme 182). In the “Si NMR spectrum, the Si- signal appeared at ca. 6 = 123 ppm, deshielded relative to 35“. The Ni in 35™ has a trigonal planar environment with a short Ni-— Si bond distance of ca. 6 2.08 ppm, suggesting a multiple bonding character in the Ni-Si interaction due to the z- acceptor character of the Si ligand. DFT calculations show that the HOMO and LUMO in 36™ have Si-N z and 3p Si characters, respectively, with a narrow HOMO—LUMO gap. The reactivity of 36“ with small molecules stems from this electronic property: it cleaves molecular dihydrogen to complex 37“! and catecholborane to 38“. The structure of 38™' revealed the first example of terminal hydroborylene (formally B') coordinated to the trigonal planar Ni" and to two HCs that migrated from Ni. The metrics of the Ni-B-Si moiety and DFT calculations imply the presence of an “agostic” Ni-B-Si interaction. The formal reduction of B” in BH(cat) to B' and the concomitant cleavage of strong B—O bonds takes place via a sequence of o-bond metathesis steps and is compensated by the formation of two strong Si-O bonds (Scheme 182).>””](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_167.jpg)

![Scheme 182. Reaction of [Ni(1,5-COD),] with the NHC- Stabilized Acyclic Silylene](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_168.jpg)

![Scheme 183. Synthesis and Reactivity of [Ni(NHC)(n°- arene) ] Complexes InPr and IMe analogues. Furthermore, in comparison to isostoichiometric complexes [NiL,(CO),] with other donors L = PMe;, PiPr3, PPh3, or L, = diethylphosphinoet hane, bipy, there is clear evidence of the superior o-donor properties of the previous section, bulkier aryl-substituted NHC i(NHC)(CO),]. However, the tetrahedral com of IMes or ICy. The A, stretching mode of the ICy the IR spectrum appears at 1948 cm‘. reaction with [Ni(CO),] provide complexes of HCs for this metal fragment. **” As mentioned in the igands on the type plexes [Ni- (IMes), (CO),] and [Ni(ICy),(CO),] were prepared by following an alternative strategy, from the three- i(NHC)(CO),] (NHC = ItBu, IAd) with two equivalents coordinate complex in Calorimetric measurements based on the substitution of [Ni(NHC)(CO),] (NHC = I¢Bu, IAd, by IMes and ICy) gave an estimation of the BDE of Ni—ICy of ca. 30.1 + 3.0 kcal/mol and Ni—IMes of ca. 27.5 + 3.0 kcal/mol, in accordance with IR spectros- copy.®](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_171.jpg)

![3.2.2. Mononuclear Ni! Complexes. 3.2.2.7. Monoden- tate NHC Ligands. 3.2.2.1.1. Homoleptic [Ni(NHC),]* and [Ni(NHC)3]*. The synthesis of the Ni! homoleptic, two- coordinate, formally 13 valence electron complex [Ni(RE-6- 3.2.1.2.2. Type [Ni(Lig).]. The homoleptic square planar Ni"! complexes 54a™!, 54b™ and 56aN!, 56b™ served as starting materials for the synthesis of the homoleptic Ni° species 55% and 57™! via the reduction of the square planar (PF,)~ salts 54b™ and 56b™ with KC, (Scheme 187). All Ni” and Ni° complexes were diamagnetic; in addition, the latter showed](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_174.jpg)

![Scheme 188. Ni° and Ni! Complexes with a Tripodal Tris-NHC Ligand ip Ip gi Mes), |Br (7aN') was mentioned in conjunction with the description of the Ni° species 7b“! (Scheme 164). It represents a rare two-coordinate Ni’ species and the only Ni’ homoleptic NHC complex. Despite its electron deficiency and low coordination number, it is relatively air-stable, presumably due to the metal center protection provided by the mesity wingtips. The structure of 7a™ revealed a highly linear system with Ni-—Cyyc distances of ca. 1.94 A. DFT calculations initially focusing on 7b™' gave an insight into the manifold o the five occupied Ni orbitals with a 2:1:2 splitting pattern and two groups of two approximately degenerate orbitals; remova of one electron maintains the degeneracy, which is important to explain the magnetic properties of 7a, however, DFT is limited on how to describe exactly the electronic structure of 7a™'. The orbital degeneracy results in unquenched first-order orbital angular momentum, which generates magnetic anisotropy and single-ion magnet (SIM) behavior for 7a. The magnetic moment in solution (Evans’ method) and the solid state (Gouy balance) gave /i.g values of 2.2 4g and 2.7 pl, respectively; in addition, 7a“! is EPR silent, a fact also attributable to the unquenched orbital angular momentum leading to large g shifts. SQUID measurements gave yT = 1.12 cm? K mol™! at room temperature, exceeding the theoretical spin-only value (0.375 cm* K mol! for a 3d’ center). The discrepancy can originate from the anisotropy of the Ni’ ion: the partially filled, degenerate highest lying d,, and d,, can interconvert by rotation of 90°, and the orbital angular momentum is not quenched by the ligand field ensuing in magnetic anisotropy. The magnetic relaxation in 7aNi was studied hy ac maonetic suscenhbility: meacurementee! Scheme 189. [Ni'(Amido)(NHC)] Complexes and their Reactivity](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_175.jpg)

![Scheme 191. Synthesis of [Ni(NHC)(Amido)] Complex from a “Ni-ate” Precursor](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_177.jpg)

![Scheme 192. [Ni!(Alkyl)(NHC)] and Related Complexes and their Reactivity Ni’ center were observed (in 80™'). With the Bu-substituted amidate, the structure of the isolated complex revealed x'-N amidate coordination in addition to the presence of dual- supporting 6-bis(C—H) agostic (or bifurcated 7°-H,C) interactions, resulting in an overall pseudo-T-shaped coordi- nation geometry (in 81). Finally, with the iPr-substituted](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_179.jpg)

![from 86a™ to form the monomeric two-coordinate moiety [NiCl(IPr)] in situ or the dinuclear 60%’; 86a‘ can thus be considered as a possible resting state of reactive [NiCl(IPr)] under catalytic conditions. The reaction of 60™ with the diphosphines 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane (dppe) or 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)propane (dppp) gave mixtures containing [Ni°(diphosphine),] and [Ni"Cl,(IPr)]; however, the reaction with 1,4- bis(diphenylphosphino )butane gave the binuclear Ni! complex 86d“, which converts only slowly to [Ni°(diphosphine),] and [Ni"Cl,(IPr),]. These results may be accounted for by the need for close proximity of the Ni’ centers to disproportionate via electron transfer to Ni° and Ni" Complexes of type [Ni'X(NHC)L] have been obtained with a limited number of bulky NHCs. Addition of L (L = PPh;, P(OPh); or pyridine) to 60™ resulted in the generation of the three-coordinate Y-shaped monomeric Ni’ complexes 86a\'— 86c™! (Scheme 194). In solution, PPh; can easily dissociate](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_181.jpg)

![88aN'—889"' did not show any evidence of a monomer— dimer equilibrium or dissociation of the NHC or PPh;; in this respect, they differ from the T-shaped [NiCI(IPr),] (see below). The EPR spectra of 88a'—88g™' display a rhombic g parameter and are broadened due to large superhyperfine coupling to the *'P and ”*'Br nuclei. The EPR spectral parameters as a function of the distortion in the trigonal planar](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_182.jpg)

![calculations were used to differentiate the electronic structures of T-shaped and Y-shaped geometries within the above family of complexes. The SOMO in T- and Y-shaped complexes has dy». and d,, character, respectively, and the T-shape is generally favored for d? complexes, but a Y-shape results in increased charge transfer from the ligands to the metal.*”° (DAC)}] (97i%).°°* Lastly, the complexes 97e™', 97£%' with aryl-substituted Cp were obtained by the reduction of the binuclear-substituted cyclopentadienyl bromide with KC, in the presence of NHCs.*”” Importantly, a salt metathetical methodology with one equivalent of NaCp or Lilnd gave the diamagnetic binuclear complexes 99a™', 99b™' and 100a™', 100b™' featuring a Ni',(u-Cl) core bridged by one cyclo- pentadienyl and one indenyl group, respectively, and inseparable minor amounts of 97a’, 97bN! and 98a™', 98b™., The 'H NMR spectra of 97aN'—97i™' and 98a, 98b™! are paramagnetically shifted (in the range from 6 +20 to —SO ppm). Their structures in the solid state are not symmetrical: they comprise planar 7°-Cp or -indenyl ligands with equal C— C distances within the five-membered rings, Cyyc-Ni-Cp- (centroid) or Cyyc-Ni-indenyl(centroid) angles subtended at Ni in the range of 154—165° (with higher values observed with the bulkier RE-Mes NHCs and Cp*) and NHC yaw of ca. 7— Scheme 197. Synthesis and Reactivity of Ni'(7°-Cp)(NHC)-Type Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/table_026.jpg)

![Scheme 199. Diverse Reactivity of [Ni(7°-Cp)(NHC)] Complexes butterfly like cores [Ni(NHC)(CO)],(w?:7*:7?-(P,)2); the P—P bond distance in 110a™! (2.08 A) is close to the value associated with P=P double bond (2.04 A) (Scheme 200). The As—As bond distance in 111a™' is ca. 2.30 A. NMR spectroscopic data support the presence of the solid-state structures in solution. Reaction of 97a“! with 0.5 equiv of [Na(dioxane),][PCO] gave the diamagnetic [{Ni- (1Pr)},(27:99,9-Cp) (u?:17,7-PCO)] (112a™), the structure of which features a symmetrical binuclear species with Ni', (Scheme 213). It is plausible that after association of the isothiocyanate reagent with 97a, the 7°-Cp undergoes rearrangement to 7'-Cp followed by homolysis of the Ni-Co, bond to provide a Ni’NHC species, on which the two isothiocyanates would undergo a reductive coupling as described previously for 1 3qni® 358](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_185.jpg)

![Reaction of 97a%' or 97cN' with the anions of the [Na(dioxane),.][P,CO] (P, = P, As) salts (one equiv) gave the complexes 110a™', 110a™' and 111a%4, 111a™' with](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_186.jpg)

![Scheme 201. Synthesis of Complexes [Ni(Halide)(NHC),] can convert to [Ni”ArXL,,] or [Ni'XL,] complexes stabilized by the phosphine. _ —](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_187.jpg)

![Scheme 202. Stoichiometric Reactions Related to Cross- Coupling by [NiX(NHC),]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_188.jpg)

![Scheme 203. Synthesis and Reactivity of [Ni'(Imido)(NHC)] Complex structure comprises a linear (ca. 174.2°) Ni center with very short Ni—N bond distance (1.66 A) and nearly linear imido group (1 presence 71.6°). These metrical data are in agreement with the of a-bonding; the heterocyclic plane of the IPr* and the plane of the central C,H; aromatic group of the Mes- terpheny form a dihedral angle of ca. 41°. SQUID magneto- metry measurements show that 119™ has a triplet ground state in the so id-state (2.77 fg) with large zero field splitting (D = 24 cm7'). DFT calculations demonstrated that one o* antibonding (d,,) orbital was stabilized (becoming non- bonding orbital; t 3d,,) are by a symmetry-allowed admixing with the 4s Ni he two degenerate SOMO x* molecular orbitals (3d,,, responsible for the multiple bonding. Based on the d orbital occupation, the bond order is 2. 00% yields, respectively (reactions D and E). The origin of mesitylene may be traced to mesityl radical formation catalyzed by [Ni'Br(IMes),], which then abstracts a H’ radical from the solvent. It has been proposed, based on the evidence presented above, that the reaction of [Ni'Br(IMes),] with BPh(OH), gave the unstable [Ni'Ph(IMes),], which is susceptible to the formation of Ph radicals that dimerize to biphenyl. The stoichiometric reactivity presented here can eliminate the involvement of two electron oxidative addition steps for the Kumada-type cross-coupling in the system Ni/ bulky NHC. The involvement of Ni'/Ni'” cycle (e.g., by the reaction of aryl halides with [Ni'(Ar)(IMes),]) or bimolecular mechanisms is plausible.*°? Under catalytic conditions, 115bX™' (X = Cl), in the presence of excess IPr, is an active catalyst for the Kumada coupling of Ph-Br or p-OMe-C,H,Br with Ph-MgBr, resulting in high yields (89-93%) of heterocoupled product (1 mol % of 115bX™', 5 mol % IPr, THF, room temperature, 18 h);*0 in contrast, it is inactive in the Suzuki cross-coupling reactions. Interestingly, the mono- nuclear Ni complex 86a™! (see above Scheme 194) was active in Suzuki cross-coupling reactions.*”!](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_189.jpg)

![Scheme 205. Stoichiometric and Catalytic Reactions of Fluorinated Nickelacycles Stabilized by the [Ni(NHC)] Moiety Scheme 205. Stoichiometric and Catalytic Reactions of Fluorinated Nickelacycles Stabilized by the [Ni(NHC)] Moiety [NiCl,(“cAAC)(PPh;)] (127fCI™), which was converted to the ion-pair (cAAC-H)* [NiCl,(PPh3) |" by adventitious acidic impurities (Scheme 206).*° a Get](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_191.jpg)

![The complex trans-[NiCl,(IPr)(2,6-lutidine)] (130™) has been obtained during studies of the photoactivation of [Ni(p- C1)Cl(IPr)], (129%') toward dehalogenation (Scheme 207).*'° Thus, the binuclear 129%‘, which is obtainable by crystallization as square-planar diamagnetic (from dichloro- methane/ pentane) or tetrahedral paramagnetic (from toluene/ hexanes) species, reacted with 2,6-lutidine with cleavage of the binuclear structure and formation of the trans-[NiCl,(IPr) (2,6- lutidine)] (130™). In addition, photolysis of 129™' led to the binuclear 60“, which oxidatively added HCI from lutidinium hydrochloride to give again 130“ (Scheme 207).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_193.jpg)

![Scheme 210. Action of O, on [Ni(Halide)(7?-allyl)(NHC)] and Derivatives related reaction with the 1-phenyl-substituted a employed to identify cinnamaldehyde and as the less volatile organic oxidized products analogous reaction. The proposed mechanism of of the Ni-bound allyl involves reversible Ni followed by the formation of a Ni in which an oxygen radical abstracts hom from the allyl group; this leads to intramo Iyl ligand was phenyl vinyl ketone formed in an the oxidation binding of O, to the peroxide intermediate, olytically an H atom ecular hydroxylation Il and the formation of a-hydroxy allyl species, which is set up for a hydrogen atom transfer to yield t mononuclear hydroxy-nickel complex; the latter dimerizes via hydroxide bridging (Schem reactivity relationships esta e 210).* blished IMes complexes, complete iner complexes but moderate reactivity min) with smaller NHCs li ke IpTo to correlate the reactivity with the failed. The discrepancy was conformational freedom o rational Ni-NH he carbonyl product and a '! The study of structure— facile oxidation of IPr and tness of IfBu and IAd (ie., O, stability for >30 . Furthermore, an attempt %Vbur Of the NHC ligand ized by considering (i) the C originating from unre- stricted rotation around the Ni-Cyyc bond and (ii) the](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_194.jpg)

![Scheme 209. Inhibiting Action of 1,5-COD in Catalytic Reactions with [Ni(1,5-COD),] and SIMes active forms may require forcing conditions. In contrast, complexes 13g—j‘' present a higher kinetic barrier for the formation of inactive 7°-allyl complexes. Experimental proof of these trends was provided by the higher activity of 13i%' in the hydroarylation of alkynes, which proceeded under milder conditions than when using [Ni(1, S- COD),] and IMes as catalyst precursors (Scheme 209).*** Robust Ni(n>-cyclo- octenyl) complexes with metalated IfBu have been obtained by the reaction of ItBu with [Ni(1,5-COD),] (Scheme 162).](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_195.jpg)

![Cyc bonds, which slows down for the bulkier NHCs and the Cp* analogues. se — Ni-—C yiavolylidene bond, which enables facile carbene dissociation and coordination to a different nickel center.’’” Complexes from the series 143™, 143a'-143g™, also catalyze the hydrosilylation of aldehydes and ketones with SiH,Ph, at room temperature in the presence of a catalytic amount of sodium triethylborohydride. The Ni hydride species [NiH(7°- Cp)(IMes)], independently synthesized by the reaction of [NiCl(7°-Cp)(IMes)] with KHBEt, and structurally charac- terized, was found to be the catalytically active species.*** Finally, 143a™ is an efficient catalyst for the @-arylation o acyclic ketones with aryl halides (chlorides, bromides, and iodides) in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of base (NaOtBu). Although polar mechanisms and the plausible C- enolate or aryl complexes [Ni(y°-Cp)(kC-PhC(O)=CHMe)] and [Ni(7°-Cp)Ph], respectively, were studied as catalytic- relevant species for the arylation reaction, strong evidence was gathered i in support of radical mechanisms. = en en en eT rt we ea TT:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_199.jpg)

![Scheme 215. Metallation of Acetone and Nitriles by [Ni"(7°-Cp)(NHC) ] Derivatives in the Presence of KOfBt](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_200.jpg)

![Ni-—Cyyc bonds of ca. 1.93 A and Ni-Ca,; of ca. 1.91 A; 148a™' was crystallographically characterized only as aquo- solvate featuring Ni-F---H-OH hydrogen bonding (Scheme 217). Solution fluxionality of 148a™' studied by 'H NMR spectroscopy was attributed to restricted rotation of the IiPr around the Ni—Cyyc bond. When using decafluorobipheny] as 1 substrate, the reaction took place at the C—F bond para to the C.F, substituent; analogous regioselectivity was observed with octafluorotoluene and (pentafluorophenyl)-trimethylsi- lane, both leading to the p-metalated complexes 151%) and 152), respectively.°°**' The chemo- and regio-selectivity of the reaction was studied in more detail with a range of partially fluorinated isomeric fluoroarenes; in all cases, C—F (and not C—H) activation was only observed, leading to complexes 153N\-157™ presumably due to superior Ni—F bond strength (compared to Ni-H).**° A range of derivatives of 148a™' were obtained by reactions with trimethylsilylated reagents of nucleophilic alkali metals, leading to substitution of the fluoride at Ni and the products 148b‘i—148e™', after trimethylsilyl fluoride or LiF elimination. All derivatives except the hydride 148e™ feature good thermal stability; all maintain the square planar geometry at Ni. Interestingly, the Ni-H of complex 148e™ appears at 6 —13.7 ppm as a deceptively simple septet, attributed to coupling with the fluoride atoms of the trans situated C,F,.*°? Complex 148e™ adopts a square- planar, albeit more distorted structure, due to the reduced steric requirements of the hydride ligand. Further metalation of the C.F, groups of 148“! and 150“ was carried out by addition of one-half more equivalent of 10“, leading to the binuclear species 149“! and 150“! (Scheme 217). In the binuclear species, replacement of the fluoride by chloride and derivatization of the Ni-—F bonds by aryl chalcogenides (leading to 149cN, 149d™' and 150c™,, 150d, respectively) was also made possible by the use of trimethylsilylated reagents.*** The complex 10%! and the related mononuclear analogue [Ni(IiPr),(7’-C,H,)] (22™)) also activate the C—F bonds in fluorinated heteroaromatics (e.g., pentafluoropyr- idine), leading to trans-[NiF(C;NF,)(IiPr),]; at lower temper- ature, the para-regioselectivity is maintained, while at room temperature, a mixture of o- and p-substituted complexes (2:1) is observed by 'H NMR spectroscopy.**?](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_201.jpg)

![Y = Cl: Z =H; 4-CO2Me; 4-C(=O)H; 4-OMe; 4-H2NCgHy; 4-CF3; 4-Cl; 3-Cl; 2-Cl; 4-F Y = Br: Z = H; 4-Me; 4-MeC(=O); 4-MeO; 4-MeS; 4-Me2N Scheme 219. Oxidative Addition of Aryl Halides to [Ni(IiPr),] Moiety](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_204.jpg)

![Scheme 220. C—C Bond Activation of Biphenylene by the [Ni(IiPr),] Moiety calculations show that a plausible intermediate preceding the C-C cleavage is a complex in which Ni(IiPr), is 7*- coordinated to the four-membered ring of biphenylene. The reaction of biphenylene with diphenylacetylene is efficiently catalyzed by 10“ to give 9,10-di(phenyl)phenanthrene.***](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_205.jpg)

![Scheme 222. Stoichiometric Reactions of [Ni(IiPr),] Moiety with Silanes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_206.jpg)

![flexible methylene linkers has been prepared: the imidazolium salts prepared by quaternization of the BINAP iodide precursor with methylimidazole were subjected to reaction with [Ni(acac),] in NMP at 200 °C, giving rise to the trans- bis(NHC) Ni complex (Scheme 225).*°? The synthesis of complex 44a™! from [NiBr,(DME)] and the free dicarbene 43a was previously described (Scheme 184).°”” imidazolium salts with [Ni(OAc),] in molten N(nBu,)Br. Furthermore, abstraction of the bromides with NaPF, and in the presence of 2,2’-bipy led to the cationic 183a™', 183b™' and 183c™, 183d‘, which constitute rare examples of [Ni- (NHC),L,]** species (see also above). The study of the redox behavior of 183a™', 183b™! and 183c', 183d™! revealed that reversible redox couples are attained with 183c™, 183d™, which was attributed to structural ligand rigidity, which inhibits dramatic geometrical changes and reorganizations during the reduction, thus facilitating reversibility. The first reduction event (—1.54 and —1.59 V vs Fc*/Fc) was assigned to bipy ligand-centered reduction, while the second was metal-based. The assignments were confirmed by DFT calculations; in the Increasing the length of the linker (i.e. using a 1,3-propylene linker, as in the bis-imidazolium salts 181a™! and 181c™') has a dramatic effect on the observed coordination chemistry. The favored formation of the dicationic homoleptic complexes seen with shorter linkers is suppressed, and the 182a™ and 182c™! cis-dibromide complexes are formed by reacting the](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_209.jpg)

![Scheme 226. Ni Complexes with Bis-NHC Ligands with Long Flexible Linkers The reaction of L” with [NiMe,(bipy) ] gave the cis-dimethyl complex 184™' featuring distorted square-planar geometry and cis methyls; in contrast, reaction with L’®" led to intractable mixtures, even though at temperature above —S0 °C signals attributable to [NiMe,(L’®")] could be observed, that were persistent in solution for 24 h. Reaction of trans- [NiMe,(PMe;),] with L'" gave the binuclear complex 185“ which was characterized spectroscopically and crystallo- graphically. When 185i was warmed above 50 °C, decomposition was observed with concomitant exclusive formation of methane and surprisingly no ethane (Scheme 227) 464465](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_210.jpg)

![Scheme 228. Ni” Complex with Bis-NHC Ligands with (BH,)~ Linker The bulky tris(carbene)borate ligand was used to stabilize four-coordinate pseudotetrahedral nickel bromide and nitrosyl complex 187™ and 188%’, respectively. They were obtained by salt metathetical reaction with [NiBr, (PPh), ] and [NiBr- (NO)(PPh;),], respectively (Scheme 229). ” Tn the para- magnetic 187™,, the tris(carbene)borate ligand is coordinated to Ni in a tridentate fashion with Ni-Cyyjc ca. 1.99 A; the bulky tBu substituents create a C; symmetric pocket and hamper the coordination of a second scorpionate ligand to the metal center. Complex 187™' is related to the isostructural hydrotris- (3-tert-butylpyrazolyl)borate nickel bromide. High frequency EPR spectra of 187%! were analyzed in detail and are characteristic for a triplet state powder pattern. The diamagnetic 188™, formally a [NiNO]'° complex, features a linear nitrosyl ligand which could imply a Ni° center. However, based on metrical data (mainly the short Ni-NO bond of ca. 1.62 A) and IR spectroscopic data [v(NO) = 1703 cm7'], the preferred formulation of NO is (NO)*" and the oxidation state of the metal Ni’. re <r ONT 7 . . _](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_212.jpg)

![Hz); the value of the coupling constant is higher than values for Si-M-H complexes obtained with complete oxidative addition of Si-H bonds to transition metals; the large value of the minimum T, (1319 ms) and IR data were in accord with 1 °-(Si-H) agostic coordination. Use of the chelating dmpe (bis(dimethylphosphino ethane) instead of PMe; afforded the tetrahedral mixed NHSi—NHC chelate stabilized Ni? complex 225“, Furthermore, the carbonyl complex 224™ was obtained by the reduction of 220“ with K(BHEt,) under a CO atmosphere. Complex 224™! features a Ni° center with Ni—Si distances longer than in 225™,, possibly due to the stronger z- acidity of CO compared to the P donors of dmpe, which results in decreased a-backdonation from the Ni to the silicon. The IR stretching vibrations for the CO ligands are seen at v = 1952 and 1887 cm™? (cf. v = 1991, 1927 cm™! and 2050, 1877 em! in [Ni(dmpm)(CO),],*** and [Ni(IMes),(CO),], respectively [dmpm=_ bis(dimethylphosphino) methane) ]. This suggests that the NHSi—NHC is a stronger o-donor than two phosphine or IMes ligands. Complex 220™ shows a high activity for the Kumada cross-coupling reactions of aryl halides (halide = Cl, Br, I) with p-tolyl- or tBu-MgCl.**” The O-enolate functionalized NHC nickel phenyl complexes 226a™ and 226b™ were prepared in one pot by the reaction of [Ni(1,5-COD),] with PhCl, two equivalents of NaN(SiMe;),, and the corresponding a-arylimidazolium-substituted aceto- phenone proligand, which bears enolizable methylene protons (Scheme 237). The complexes are square-planar with very short Ni—Cypc and Ni-—Osnolate bond distances of 1.85 and 1.89 A, respectively; the latter are slightly shorter than those observed in analogous diphenylphosphinoenolate complexes (ca. 1.92 A). The aryl wingtip is almost perpendicular to the NHC and coordination planes. Toluene solutions of 226a™! and 226b™ are moderately active for the polymerization of ethylene in the absence of cocatalyst; their activity is comparable to that of SHOP-type catalysts but is lower than that of the neutral Ni salicylaldimine or cationic catalysts. A striking difference between the Ni diimine and 226a™ and 226b™ is the linearity of the polyethylene obtained with the latter, in particular at low pressures; this was attributed to the absence of “chain walking’.“*’ Attempts to induce the formation of chelate NHC-alkoxide complexes by using the f-hydroxyethyl-functionalized imidazolium or imidazol-2-yli- Scheme 237. Complexes with O—Donor Functionalized NHC Ligands](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_221.jpg)

![Scheme 241. Ni Complexes with Anionic Aryl Functionalized Abnormal NHC Ligands occurring when 243%! was reacted at elevated temperatures with the heteroarene substrate was gained by NMR spectros- copy; the disappearance of the signal assigned to the cyclometalated C-atom and the liberation of cyclooctadiene was interpreted as evidence to the formation of a 12-electron Ni°(aNHC) reactive species which undergoes oxidative addition with the C—H bonds of the heteroaryl substrate. Furthermore, the mechanism of formation of 243™ and 244™! was postulated to involve C—H activation/orthometalation of the species [Ni(aNHC)(1,5-COD)], followed by insertion of the coordinated COD into the Ni—H bond. Interestingly, DFT calculations showed a difference in the electronic structures of 243) and 244%1, In 243%! the HOMO is localized on Ni and the aNHC ligand, while in 244) it is localized on Ni and the cyclooctenyl ligand; furthermore, the HOMO of 243™ is at higher energy. These results show that in 243™' the aNHC has more electron-donating substituents and the imidazole ring higher charge population which would make the Ni center more reactive in oxidative addition reactions.’”” ‘esr](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_226.jpg)

![reaction of the bis-imidazolium and [Ni(OAc),] initially at room temperature followed by heating at 130 °C provided the dinuclear species 273a™, 273b™' in which both bridging and chelating forms of the pyridine dicarbene are present; the different outcome as a function of the temperature was attributed to initial irreversible formation of the binuclear mono-NHC complex framework, on which two additional KC,KN,kC-pyridine dicarbene ligands coordinate. In the complexes 272b™ and 273b™!, which were structurally characterized, the metal adopted a square-planar coordination geometry; the structures seen in the solid state were maintained in solution as evidenced by the symmetry of the NMR spectra.”* those of complexes with simple imidazol-2-ylidenes (6 at ca.166 ppm).°”° Finally, the rigid bis-aryloxide NHC was complexed to Ni by the reaction of the imidazolium or benzimidazolium salts 269™ with NiCl, in the presence of K,CO,j in pyridine to give the square-planar complexes 270“! with one pyridine coordinated trans to the NHC donor (Ni- Noyridine = 1.95 A due to trans influence of the NHC). The Ni- Cynic bond distance (1.79 A) is unremarkable, but the chelate defined by the donor atoms and Ni significantly deviates from planarity, presumably due to ligand imposed strain (Scheme 246).°°” Scheme 247. Ni” Pyridine Dicarbene and Related Complexes](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_232.jpg)

![Scheme 248. “i! Ni! Pyridine Dicarbene and Related Complexes yr p with the second halide being counteranion. A few of the species 274b™ were fully characterized by exchanging the halide counteranion with larger anions [i.e., (PF,)~]; the pure dichloride 274c™ comprising a coordinated and ionic chloride was obtained by substituting the halides of 274a™' with CI" originating from the DOWEX resin in methanol. On concentration, the ionic complex was converted to the five- coordinate chloride analogue 274a“ with two coordinated chlorides on the five-coordinate Ni center (Scheme 247).°'° Ag and the isolation of complex 278™. This behavior was attributed to comparable Ag— and Ni—Cyyc bond energies with the direction of transmetalation being overall determined by additional parameters (e.g., solvation, sterics, and non- bonding interactions). Since the appearance of this report, more reverse transmetalations, in particular involving Ni and Ag, have appeared. Both ionic and coordinated bromides in 275e™', 275f%' could be abstracted by treatment with two equivalents of AgBF, in MeCN, leading to the square-planar acetonitrile complex 276™', with an acetonitrile ligand coordinated trans to the pyridine. Alternatively, reaction with excess of AgOTf in THF afforded the paramagnetic octahedral THF complex 277“! with two mutually trans-disposed x'- O(SO,)CF; ligands and one THF-coordinated trans to the central pyridine (Scheme 248).°’”](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_233.jpg)

![Scheme 254. Complexes with Non-Symmetrical Pincer Ligands Featuring Internal NHC Donor donor” chelates via a Ag transmetalation protocol using one or half mole equivalent of [Ni(PPh;),Cl,], respectively. The square-planar 297“ exhibits good activity in the Kumada cross-coupling reaction of aryl chloride at room temper- ature.’ “CNN donor” chelates were also constructed from NHC, pyridine, and substituted iminophosphine donors (299% and 301") leading to the square-planar complexes 300“ and 302%‘, respectively.” Finally, the rigid “CCP donor” chelates 307™ and 308™ were accessed by a multistep sequence starting from the direct metalation of the imidazol- phosphine phosphinite 304™' with [NiBr,(iPrCN),] (iPrCN = isobutyronitrile) and leading to the P’CP pincer complex 305“. Upon quaternization of the imidazol-phosphine at the imidazole-N and reaction of the resulting cationic phosphine complex 306™ with the nucleophilic NaOEt, the CCP donor pincer complex 307“ was obtained. Its cation 308 was formed after reaction of 307% with AgOTf in acetoni- trile**°** The cationic species 308%‘ catalyzed the hydro- amination of nitriles to give unsymmetrical amidines (Scheme 253). The complexes with nonsymmetrical linear tridentate ligands where the NHC occupies the internal position are shown in Scheme 254. The nature of the complexes obtained comprising the nonsymmetrical NHC functionalized with 1,2,3-triazol and pyridine/picoline/pyrimidine wingtips de- pended on the reaction stoichiometries and the size of the spacers between the NHC and the pyridine-type function- alities. All complexes were obtained following the trans- metalation methodology and using [NiCl,(PPh;),] as Ni source. With pyridine/pyrimidine donors as the second type of wingtip, mononuclear species with 1:1 310™ or 2:1 ligand-to- i ratio 311N and square-planar or octahedral geometries, respectively, were obtained. With picoline as the second type of wingtip donor, binuclear species featuring one hydroxo bridge and square-planar Ni centers (312™) were isolated in ow yields.” The benzimidazo-2-ylidene complex 310b™ acts as catalyst for the Suzuki coupling of aryl bromides and phenylboronic acids at 110 °C.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_239.jpg)

![Scheme 255. Complexes with the Tetradentate Functionalized NHC Ligands nickelocene; they feature square-planar Ni centers and exhibit moderate to high activity toward the homopolymerization of norbornene and copolymerization of norbornene with 1- octene with B(C,F;); as the cocatalyst.*?* Finally, the chiral nonsymmetric imidazolium proligands with phosphine and pyridine donor wingtips were used for the synthesis of Ni-7?- octenyl and Ni-Cl complexes 316“ and 317%! by methods similar to those described for the symmetrical pyridine- functionalized tridentate ligand described previously (Schemes 253 and 254).°7° The tetradentate ligands bis(N-(benz)imidazolylpyridine)- methane, bis(N-imidazolylpyridine)-ethane, bis(N-imidazolyl- pytidine)-propane, a,a’-bis(N-imidazolylpyridine)-o-xylylene, a,a'-bis(N-imidazolylpicoline)-o-xylylene, and bis(N- imidazolylpicoline)methane were used to prepare the series of Ni complexes 318a“\—318k™ by reactions involving the corresponding imidazolium salts and [Ni(OAc),] (in the presence or not of (NnBu,)Br, Raney-Ni, Ni powder, or following a Ag transmetalation methodology from isolated or in situ generated Ag complexes and [NiCl,(PPh;),] or](https://figures.academia-assets.com/106328960/figure_240.jpg)