seismic analysis of structures

…

473 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

AI-generated Abstract

The paper presents an in-depth analysis of the seismic behavior of structures, focusing on the fundamental principles of plate tectonics as a precursor to understanding earthquake mechanics. It discusses the mechanisms of seismic wave propagation, interplate and intraplate earthquake occurrences, and the relevant factors influencing structural response during seismic events. Through a mix of theoretical modeling and empirical data, the research highlights the need for effective damping strategies and response analysis to improve earthquake resilience in engineered structures.

Figures (449)

![Figure 1.1 Inside the earth (Source: Murty, C.V.R. “IITK-BMPTC Earthquake Tips.” Public domain, National Information Centre of Earthquake Engineering. 2005. http://nicee.org/EQTips.php - accessed April 16, 2009.) the inner core, the outer core, the mantle, and the crust, as shown in Figure 1.1. The upper-most layer, called the crust, is of varying thickness, from 5 to 40 km. The discontinuity between the crust and the next layer, the mantle, was first discovered by Mohorovi¢i¢ through observing a sharp change in the velocity of seismic waves passing from the mantle to the crust. This discontinuity is thus known as the Mohorovici¢ discontinuity (““M discontinuity”). The average seismic wave velocity (P wave) within the crust ranges from 4 to 8kms'. The oceanic crust is relatively thin (S—15 km), while the crust beneath mountains is relatively thick. This observation also demonstrates the principle of isostasy, which states that the crust is floating on the mantle. Based on this principle, the mantle is considered to consist of an upper layer that is fairly rigid, as the crust is. The upper layer along with the crust, of thickness ~120 km, is known as the lithosphere. Immediately below this is a zone called the asthenosphere, which extends for another 200 km. This zone is thought to be of molten rock and is highly plastic in character. The asthenosphere is only a small fraction of the total thickness of the mantle (~2900 km), but because of its plastic character it supports the lithosphere floating above it. Towards the bottom of the mantle (1000-2900 km), the variation of the seismic wave velocity is much less, indicating that the mass there is nearly homogeneous. The floating lithosphere does not move as a single unit but as a cluster of a number of plates of various sizes. The movement in the various plates is different both in magnitude and direction. This differential movement of the plates provides the basis of the foundation of the theory of tectonic earthquake. Below the mantle is the central core. Wichert [1] first suggested the presence of the central core. Later,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_001.jpg)

![Table 1.1 Frequency of occurrence of earthquakes (based on observations since 1900) 1.3.5 Energy Release Newmark and Rosenblueth [9] compared the energy released by an earthquake with that of a nuclear explosion. A nuclear explosion of 1 megaton releases 5 x 10'°J. According to Equation 1.12, an earthquake of magnitude Ms = 7.3 would release the equivalent amount of energy as a nuclear explosion of 50 megatons. A simple calculation shows that an earthquake of magnitude 7.2 produces ten times more ground motion than a magnitude 6.2 earthquake, but releases about 32 times more energy. The E of a magnitude 8.0 earthquake will be nearly 1000 times the E of a magnitude 6.0 earthquake. This explains why big earthquakes are so much more devastating than small ones. The amplitude numbers are easier to explain, and are more often used in the literature, but it is the energy that does the damage. The length of the earthquake fault L in kilometers is related to the magnitude [10] by](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/table_001.jpg)

![Table 1.2 Modified Mercalli intensity (MMI) scale (abbreviated version) Although the subjective measure of earthquake seems undesirable, subjective intensity scales have played important roles in measuring earthquakes throughout history and in areas where no strong motion instruments are installed. There have been attempts to correlate the intensity of earthquakes with instrumentally measured ground motion from observed data and the magnitude of an earthquake. An empirical relationship between the intensity and magnitude of an earthquake, as proposed by Gutenberg and Richter [6], is given as The last one, which has ten grades, 1s still used 1n some parts of Europe. The Mercalli-Cancani—Sieberg scale, developed from the Mercalli (1902) and Cancani (1904) scales, is still widely used in Western Europe. A modified Mercalli scale having 12 grades (a modification of the Mercalli-Cancani—Sieberg scale proposed by Neuman, 1931) is now widely used in most parts of the world. The 12-grade Medved— Sponheuer—Karnik (MSK) scale (1964) was an attempt to unify intensity scales internationally and with the 8-grade intensity scale used in Japan. The subjective nature of the modified Mercalli scale is depicted in Table 1.2.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/table_002.jpg)

![Figure 2.9 Variation of rms value of acceleration with time for uniformly modulated non-stationary process Records of actual strong motion time history show that modeling of an earthquake process as a stationary random process is not well justified as the ensemble mean square value varies with time. The mean square value gradually increases to a peak value, remains uniform over some time, and then decreases as shown in Figure 2.9. Such type of behavior is often modeled as a uniformly modulated non- stationary process [3]. Such a process is represented by an evolutionary power spectral density function. The evolutionary spectrum is obtained by multiplying a constant spectrum with a modulating function of time ¢ and is given as:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_040.jpg)

![Figure 2.50 Exponential type modulating function in which Ag is the scaling factor and f,, f2, and f3 are the transition times of the modulating function. A modified form of the trapezoidal type modulating function [29] is shown in Figure 2.49 and is given by](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_086.jpg)

![Figure 4.4 Shaded area at frequency w contributing to the mean square value in which r? is the mean square value of the process; E[ ] indicates the expected value, that is, the average or mean value. Equation 4.26a provides a physical meaning of the power spectral density function. The area under the curve of the power spectral density function is equal to the mean square value of the process. In other words, the power spectral density function may be defined as the frequency distribution of the mean square value. At any frequency o, the shaded area as shown in Figure 4.4 is the contribution of that frequency to the mean square value. If the square of x(t) is considered to be proportional to the energy of the process [as in E(t) =!4Kx(t)*], then the power spectral density function of a stationary random process in a way denotes the distribution of the energy of the process with frequency. For random vibration analysis of structures in the frequency domain, the power spectral density function (PSDF) forms an ideal input because of two reasons:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_153.jpg)

![Figure 5.2 Variation of correlation coefficient p;; with the modal frequency ratio «; /;; abscissa scale is logarithmic pj May be ignored as it is assumed in the SRSS combination rule. SRSS and CQC rules for the combination of peak modal responses are best derived assuming a future earthquake to be a stationary random process (Chapter 4). As both the design response spectrum and power spectral density function (PSDF) of an earthquake represent the frequency contents of ground motion, a relationship exists between the two. This relationship is investigated for the smoothed curves representing the two, which show the averaged characteristics of many ground motions. If the ground motion is assumed to be a stationary random process, then the generalized coordinate in each mode of vibration is also a random process. Therefore, there a cross correlation (represented by cross PSDF) between the generalized coordinates of any two modes is present. Because of this, it is reasonable to assume that a correlation coefficient p,; exists between the two modal peak responses. Derivation of p, (Equation 5.15) as given by Der Kiureghian [2] is based on the above concept. There have heen ceveral attemnte to ectahlich 9a relatinnchin hetween the PSDE and the recnonce](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_175.jpg)

![The analysis replaces the soil by spring—dashpots as shown in Figure 7.55. The spring stiffness and damping coefficients of the dashpots are derived by combining Mindlin’s static analysis of the soil pressure at a depth within the soil and the soil impedance functions. The details of the derivation are given in references [12, 13]. The stiffness and damping coefficients of the matrices corresponding to the DOF are coupled unlike the condition of Winkler’s bed. However, a simplified analysis can be performed by ignoring the off-diagonal terms and by using the diagonal terms to assign stiffness and](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_288.jpg)

![een gn ne nnn en een ene en nen ee enn ne ne eee nn eee nn een ee nee enn nee ee ee OE The pipeline is also subjected to axial vibration along the length of the pipe due to P waves traveling along the pipeline. Analysis as described above can be carried out for axial vibration of the pipeline, with the soil being replaced by equivalent springs and dashpots. The stiffness and damping coefficients of the springs and dashpots are similarly obtained as for the case of transverse oscillation. For a simplified analysis, stiffness and damping coefficients of the springs and dashpots may be obtained by ignoring the off-diagonal terms of the soil stiffness and damping matrices. Figure 7.56 provides the frequency independent stiffness and damping coefficients of the equivalent springs and dashpots for transverse and axial vibrations of buried pipelines [12]. These coefficients may be used to obtain the stiffness and damping coefficients as follows: Figure 7.56 Variation of frequency independent spring and damper coefficients with d/r](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_291.jpg)

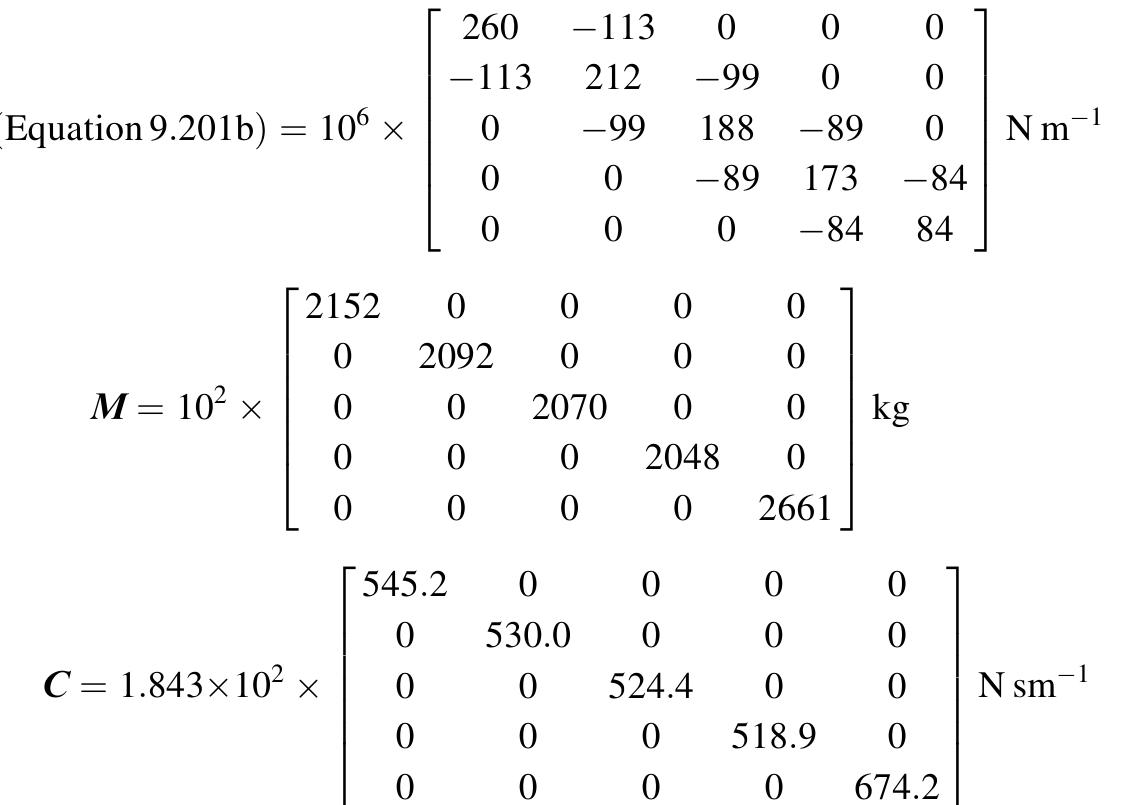

![Stiffness matrix for the structure corresponding to the DOF, shown in Figure 7.57, is obtained as: [K;], is added to the K part of the [K], matrix and then rotational degrees of freedom are condensed out. The resulting stiffness matrix is the soil—pipe stiffness matrix. For axial vibration, [K,],, is directly added to [K],,- To construct the damping matrix, [K], is condensed to eliminate 6 degrees of freedom. Assuming Rayleigh damping, [C], for the pipe is obtained using the first two frequencies of the soil—-pipe system. Note that the eigen value problem cannot be solved without adding spring stiffness to the pipe stiffness matrix. [C,], is added to [C], to obtain the damping matrix of the soil—-pipe system. In a similar way, a damping matrix for the axial vibration can be determined. Results of the computation are given below. The first two frequencies of the soil—pipe system and « and f values are:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_293.jpg)

![Figure 8.3. Hasofer—Lind reliability index with linear performance function When the limit state function is non-linear, the computation of the minimum distance becomes an optimization problem, that is, Shinozuka [4] obtained an expression for the minimum distance as:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_296.jpg)

![In the above problem, if material uncertainty is included then the limit state function takes the form where Lo is the probability of starting below the threshold, « is the decay rate, and T is the duration of the process. At high barrier levels, Lo is practically one and the decay rate is given by the following expressions with double barrier (ap) and one sided barrier (~s) respectively [12],](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_307.jpg)

![Figure 9.44 A model of Teflon coated viscoelastic damper where C|.] and DJ[.] are linear differential operators with constant coefficients. Using a Laplace transformation, Equation 9.78 provides a transfer function H(s) in the form of](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_360.jpg)

![regulator (LQR) control, pole placement technique, instantaneous optimal control, discrete time control, sliding mode control, independent modal space control, bounded state control, predictive control, H, control, and so on [11,12]. The control mechanisms, which have been developed and used in experiments and in practice, include actuated mass damper (AMD), actuated tuned mass damper (ATMD), active tendon system (AT), and so on (Figure 9.53). Active control algorithms generate the required control signal that drives the actuators of the control device. Before describing the control algorithms, it is desirable to understand the effect of control forces on the response of a structure under ideal conditions. Consider the equation of motion of a multi-degrees of freedom system under a set of control forces u:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_369.jpg)

![in which e = X—X. Equation 9.144 is similar to Equation 9.136a. For complete state controllability, that is, |A—K-.C] to be a state matrix, [A—K.C] has arbitrarily desired eigen values. Thus, K, can be designed to yield the desired eigen values. The problem is similar to finding the gain matrix G for the pole placement technique (discussed later) and can be solved by Ackerman’s formula [13]. Using Ackerman’s formula, the gain matrix K, can be obtained as:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_371.jpg)

![MATLAB computation to find the K, is explained with the following example. in which e = x,—Xp; Xp is the estimated state of the un-measured variables. K, as before can be obtained using Ackerman’s formula and is given by [13]: Example 9.7](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_372.jpg)

![For a control system described by Equation 9.149, obtain the G matrix using MATLAB for the following values of A, B, and J [13]. Note that the output matrix, that is, K of MATLAB is the G matrix. As a result, both K and G are used to denote the same gain matrix. Example 9.8A](https://figures.academia-assets.com/31938309/figure_375.jpg)

Related papers

The nature and the severity of the earth quake will be decided by the movement of the tectonic plate. Again the root cause for the movement of the tectonic plates depends upon the convection current. The root cause for creation of convection current is the structure or the formation of the earth. Until now there are 3 patterns of tectonic plate movement predicted and published by the scientist. Now I am predicting and publishing a fourth pattern of tectonic plate movement in this publication.

Proc. 5th International Symposium on Geophysics, Tanta, Egypt (2008), 1-15, 2008

Recent studies of olivine melts have confirmed rheological evidence that the seismic low velocity layer cannot be a region of partial mantle melt and is therefore not at ~1,200C yet this assumption was used for determining oceanic geothermal gradients that, in turn, were used to (1) estimate the radioactive content of oceanic mantle, (2) evaluate plate tectonic driving forces and (3) calculate thermal models of the oceanic lithosphere. The top of the asthenosphere is more likely to be at 500-900°C as is the top of the asthenosphere. If ~900C is adopted, then the oceanic geothermal gradients are corresponding less steep, the rate of mantle heat loss far loss, the concentration of radiogenic heat-producing elements in the mantle much less the oceanic lithosphere is colder and warms more slowly than currently modelled. Such considerations lead to a model of plate tectonics in which viscosity differences in the mantle derive from hydrous materials squeezed out of the liquid outer core as the inner core solidifies. These lower viscosity regions amalgamate and rise as diapirs having lower viscosities than the surrounding mantle but only marginally higher temperatures. Most phase changes in the upper mantle assist this convective flow, but the ~660km phase transition inhibits the vertical passage of mantle materials other than where they are fluidised. The descent of oceanic lithosphere remains dependent mostly on eclogite formation, with the downward passage through the ~660km transition occurring because of the presence of higher density phase (periclase and metallic iron). The lateral motion involves all of the upper mantle and parts of the lower mantle. The revised thermal model for subducting oceanic lithosphere enables intermediate and deep earthquakes to occur by brittle failure.

Geological Society of America Special Paper 433, 2007

A conceptual shift is overdue in geodynamics. Popular models that present plate tectonics as being driven by bottom-heated whole-mantle convection, with or without plumes, are based on obsolete assumptions, are contradicted by much evidence, and fail to account for observed plate interactions. Subduction-hinge rollback is the key to viable mechanisms. The Pacific spreads rapidly yet shrinks by rollback, whereas the subduction-free Atlantic widens by slow mid-ocean spreading. These and other fi rstorder features of global tectonics cannot be explained by conventional models. The behavior of arcs and the common presence of forearc basins on the uncrumpled thin leading edges of advancing arcs and continents are among features indicating that subduction provides the primary drive for both upper and lower plates. Subduction rights the density inversion that is produced when asthenosphere is cooled to oceanic lithosphere: plate tectonics is driven by top-down cooling but is enabled by heat. Slabs sink more steeply than they dip and, if old and dense, are plated down on the 660 km discontinuity. Broadside-sinking slabs push all sublithosphere oceanic upper mantle inward, forcing rapid spreading in shrinking oceans. Down-plated slabs are overpassed by advancing arcs and plates, and thus transferred to enlarging oceans and backarc basins. Plate motions make sense in terms of this subduction drive in a global framework in which the ridge-bounded Antarctic plate is fixed: most subduction hinges roll back in that frame, plates move toward subduction zones, and ridges migrate to tap fresh asthenosphere. This self-organizing kinematic system is driven from the top. Slabs probably do not subduct into, nor do plumes rise to the upper mantle from, the sluggish deep mantle.

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 2018

Plate tectonics is a particular mode of tectonic activity that characterizes the present-day Earth. It is directly linked to not only tectonic deformation but also magmatic/volcanic activity and all aspects of the rock cycle. Other terrestrial planets in our Solar System do not operate in a plate tectonic mode but do have volcanic constructs and signs of tectonic deformation. This indicates the existence of tectonic modes different from plate tectonics. This article discusses the defining features of plate tectonics and reviews the range of tectonic modes that have been proposed for terrestrial planets to date. A categorization of tectonic modes relates to the issue of when plate tectonics initiated on Earth as it provides insights into possible pre-plate tectonic behaviour. The final focus of this contribution relates to transitions between tectonic modes. Different transition scenarios are discussed. One follows classic ideas of regime transitions in which boundaries between tectonic modes are determined by the physical and chemical properties of a planet. The other considers the potential that variations in temporal evolution can introduce contingencies that have a significant effect on tectonic transitions. The latter scenario allows for the existence of multiple stable tectonic modes under the same physical/chemical conditions. The different transition potentials imply different interpretations regarding the type of variable that the tectonic mode of a planet represents. Under the classic regime transition view, the tectonic mode of a planet is a state variable (akin to temperature). Under the multiple stable modes view, the tectonic mode of a planet is a process variable. That is, something that flows through the system (akin to heat). The different implications that follow are discussed as they relate to the questions of when did plate tectonics initiate on Earth and why does Earth have plate tectonics.

Geophysical Monograph Series, 2000

We present an overview of the relation between mantle dynamics and plate tectonics, adopting the perspective that the plates are the surface manifestation, i.e., the top thermal boundary layer, of mantle convection. We review how simple convection pertains to plate formation, regarding the aspect ratio of convection cells; the forces that drive convection; and how internal heating and temperature-dependent viscosity affect convection. We examine how well basic convection explains plate tectonics, arguing that basic plate forces, slab pull and ridge push, are convective forces; that sea-floor structure is characteristic of thermal boundary layers; that slab-like downwellings are common in simple convective flow; and that slab and plume fluxes agree with models of internally heated convection. Temperature-dependent viscosity, or an internal resistive boundary (e.g., a viscosity jump and/or phase transition at 660km depth) can also lead to large, plate sized convection cells. Finally, we survey the aspects of plate tectonics that are poorly explained by simple convection theory, and the progress being made in accounting for them. We examine non-convective plate forces; dynamic topography; the deviations of seafloor structure from that of a thermal boundary layer; and abrupt platemotion changes. Plate-like strength distributions and plate boundary formation are addressed by considering complex lithospheric rheological mechanisms. We examine the formation of convergent, divergent and strike-slip margins, which are all uniquely enigmatic. Strike-slip shear, which is highly significant in plate motions but extremely weak or entirely absent in simple viscous convection, is given ample discussion. Many of the problems of plate boundary formation remain unanswered, and thus a great deal of work remains in understanding the relation between plate tectonics and mantle convection. ¥ , thermal expansivity ¦ , dynamic viscosity § , thermal diffusivity¨, the layer's thickness © , and the gravitational field strength (acting normal to the layer and downward). These properties reflect how much the system facilitates convection (e.g., larger ¥ , , and ¦ allow more buoyancy) or impedes convection (e.g., larger § and¨imply that the fluid more readily resists motion or diffuses thermal anomalies away). The combination of these properties in the ratio " ! gives a temperature that ¡ ¤ ¢ must exceed in order to cause convection. The Rayleigh number is the . Black represents cold fluid, light gray is hot fluid. The temperature field shows symmetric convection cells, upwellings, downwellings and thermal boundary layers thickening in the direction of motion (at the top and bottom of the layer, in between the upwellings and downwellings). dimensionless ratio of these temperatures © ¥ ¦ ¡ ¤ ¢ © § and therefore indicates how well the heating represented by ¡ ¤ ¢ will drive convection in this system. Stability analysis predicts that the onset of convection, triggered by the least stable mode, will occur when

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Related papers

Nature, 2013

2004

Geographical Educational Magazine, 1994

Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2002

Terra Nova, 2010

Nature, 2014

Tectonophysics, 1982

Journal of Geophysical Research, 1999

Science, 2002

Lerner, K. Lee. Continental Drift and the Theory of Plate Tectonics. Draft Copy. Originally published 2002, revised and published in Scientific Thought: In Context. Cengage | Gale, 2010.

Tectonophysics, 2012

Tectonophysics, 1993

Terra Nova, 1997

Journal of Geophysical Research, 1968

César Osses Espinoza

César Osses Espinoza