Structural Behaviour of Long Concrete Integral Bridges

2011

…

290 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

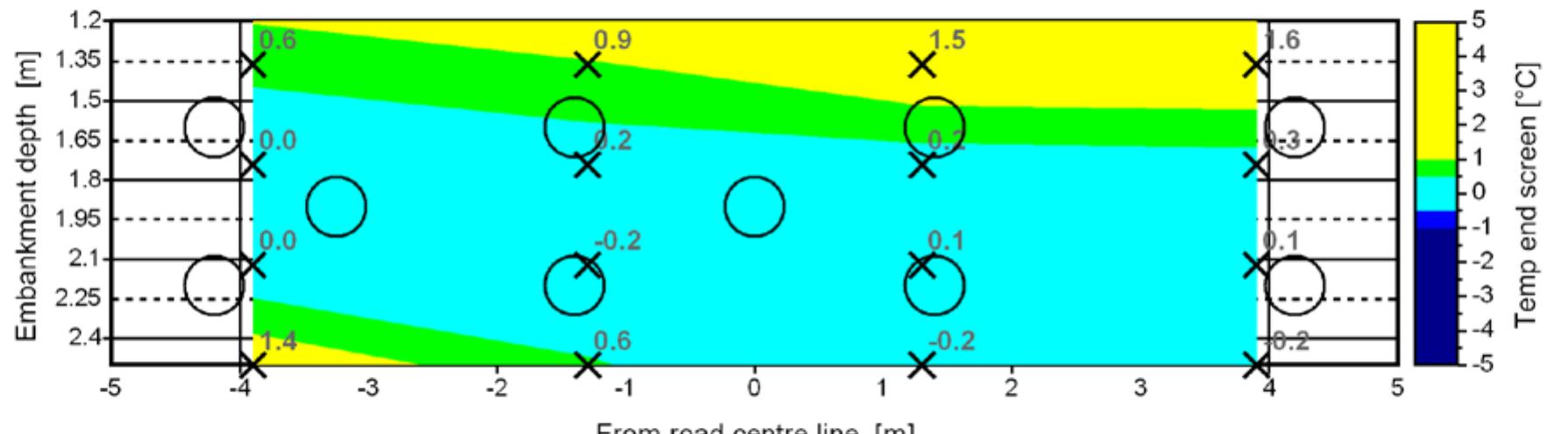

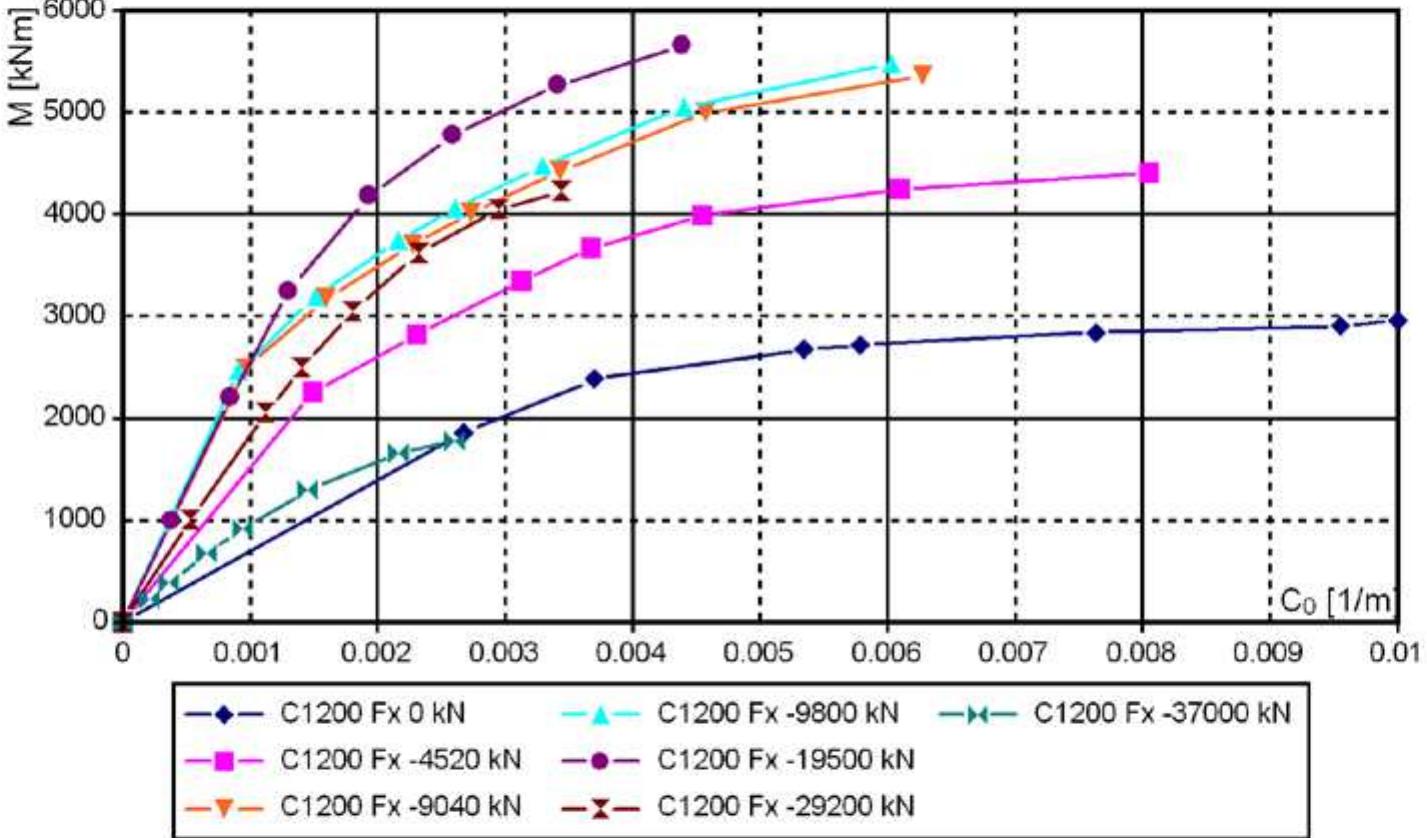

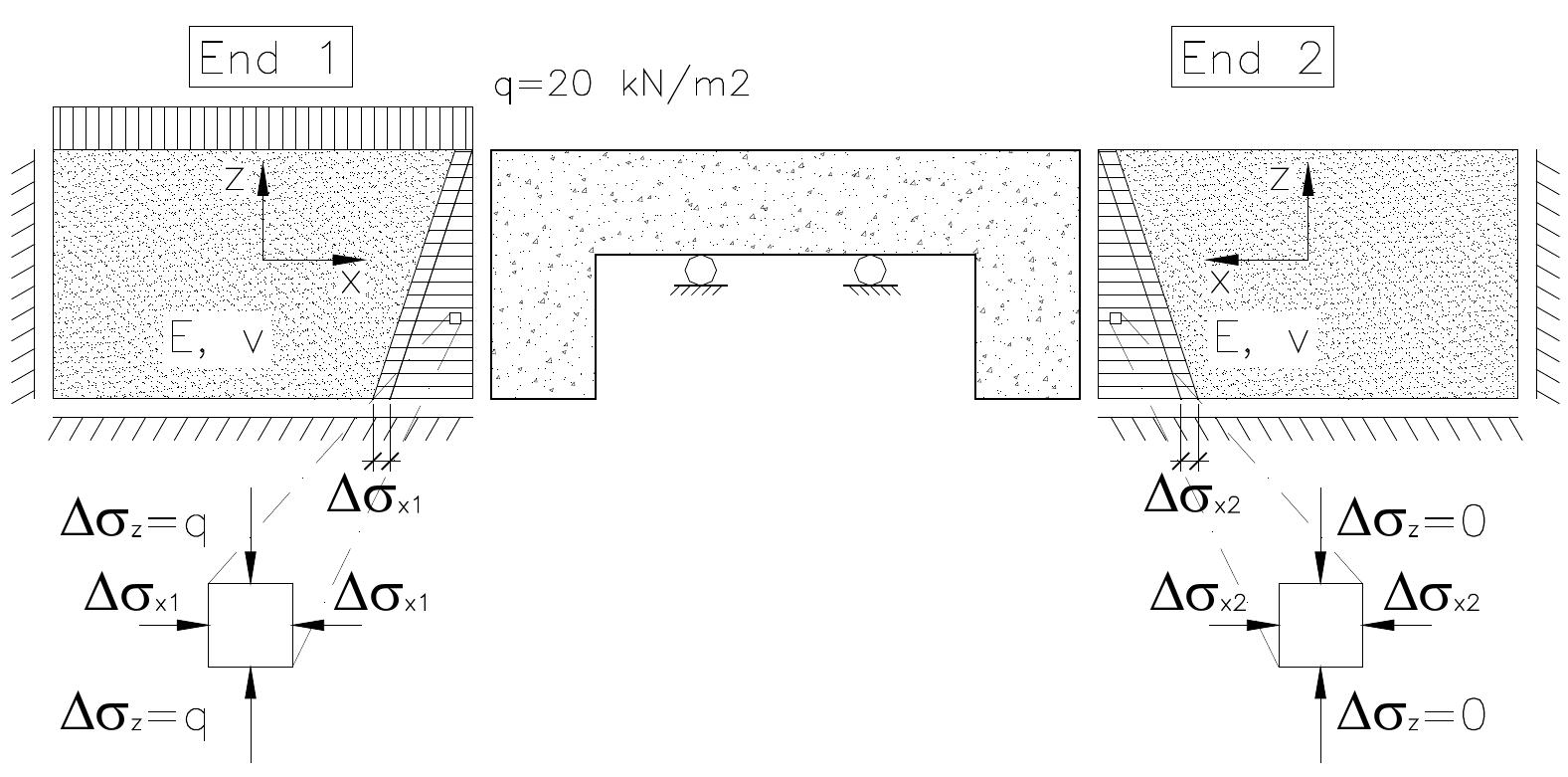

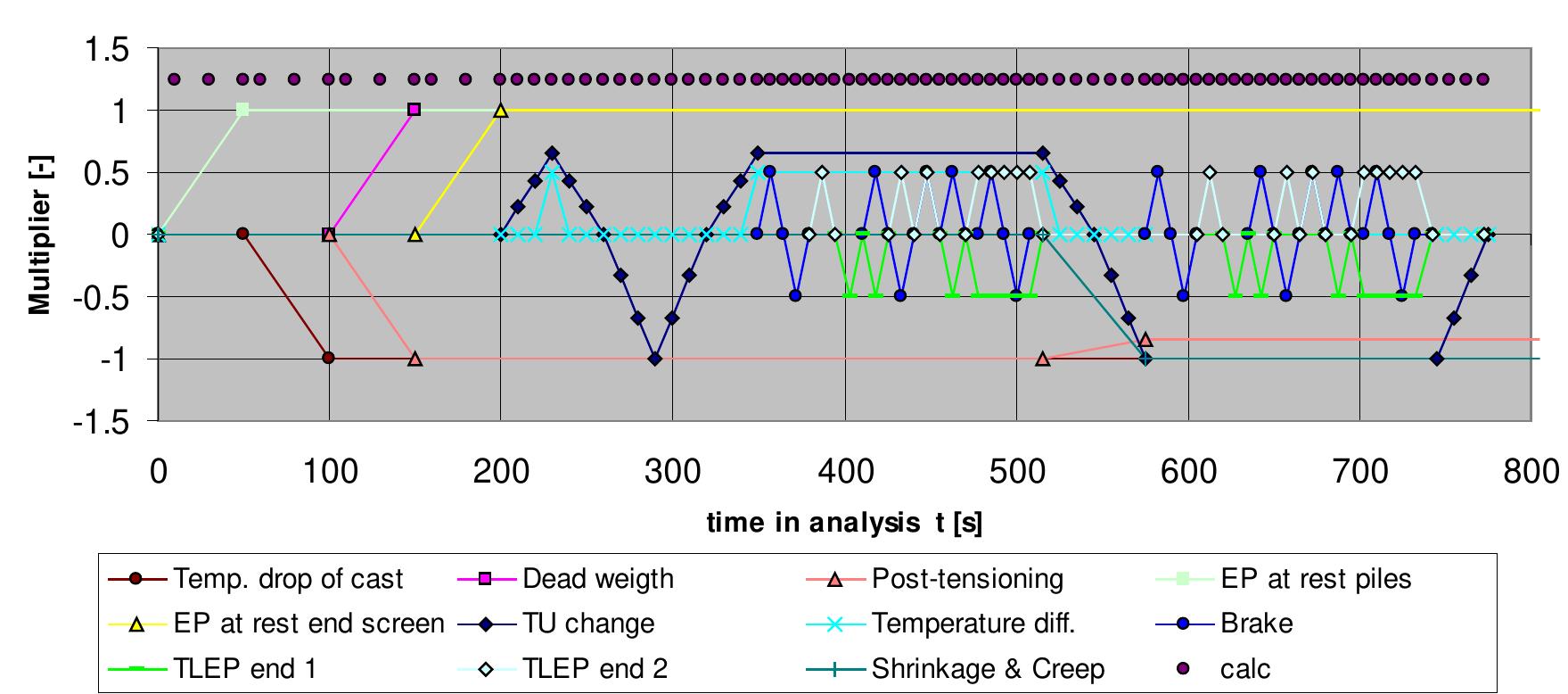

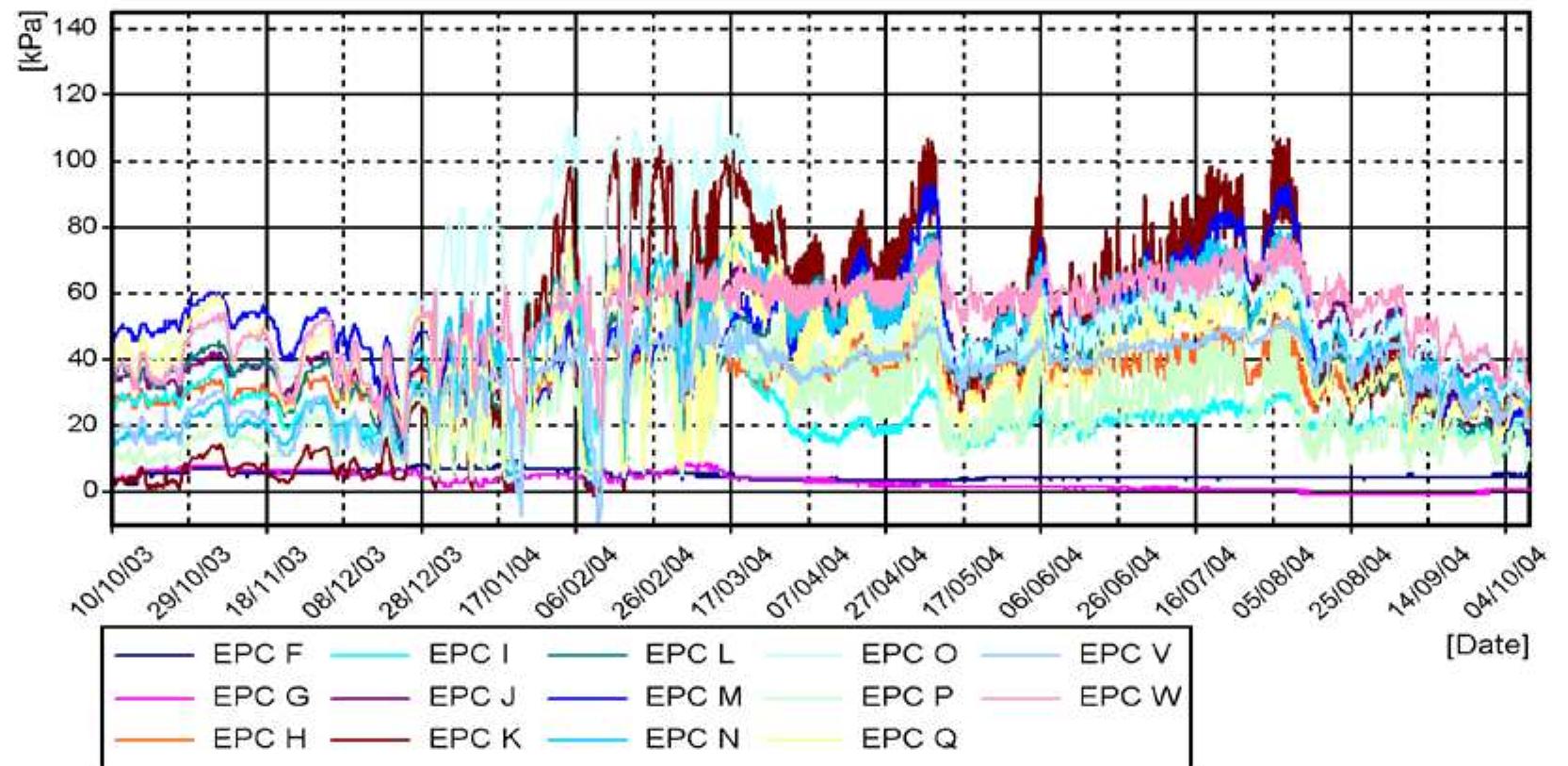

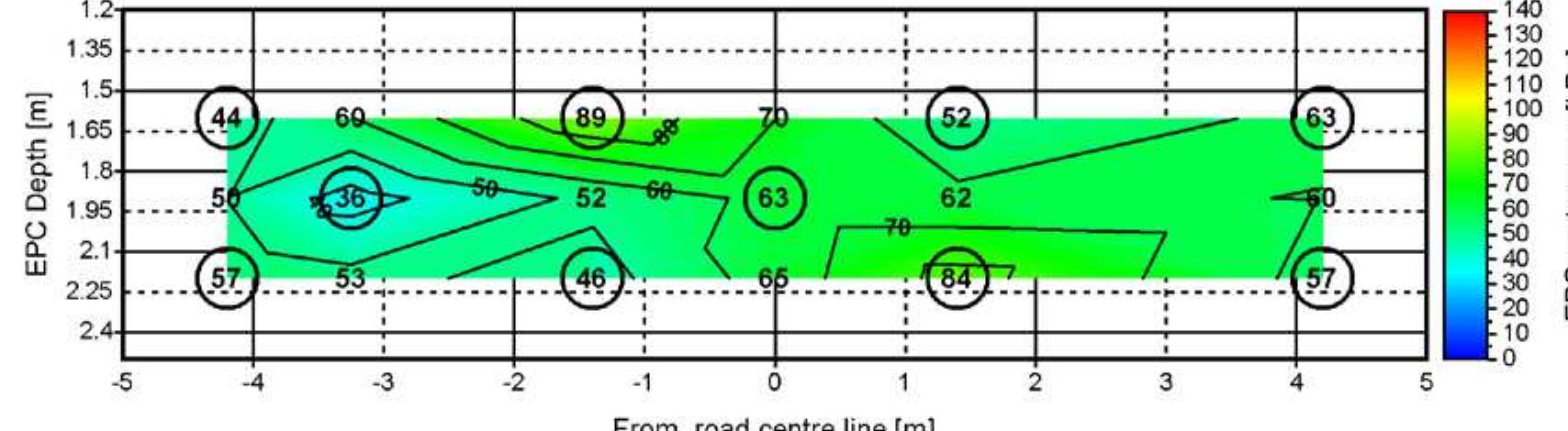

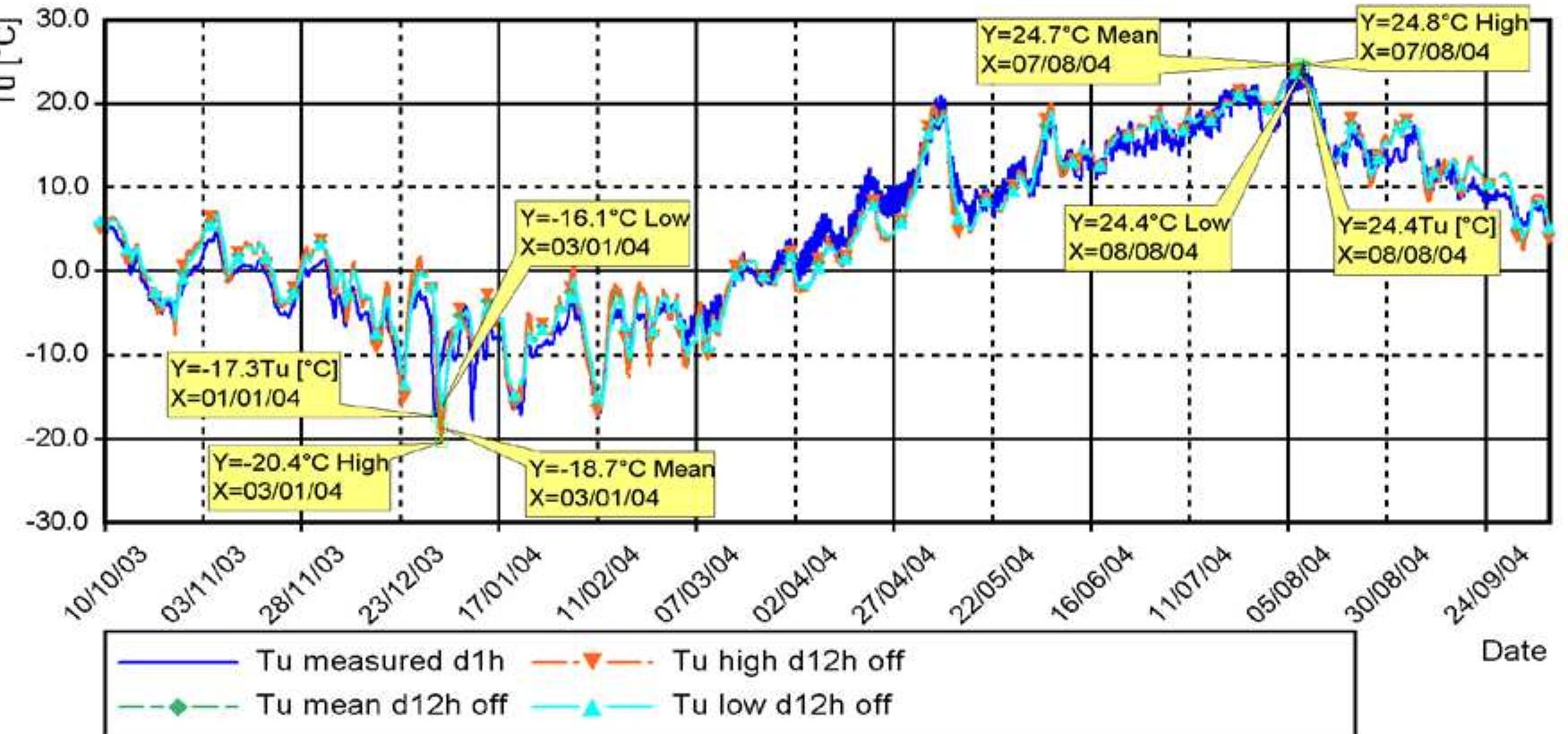

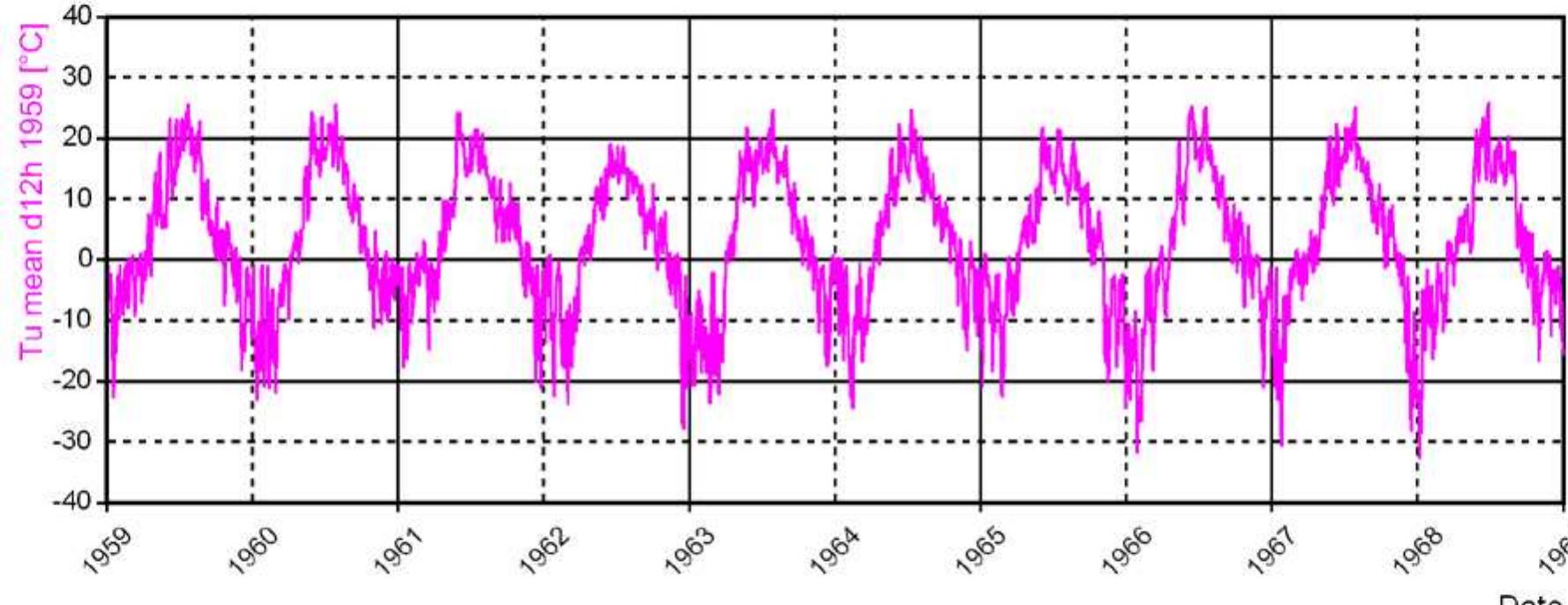

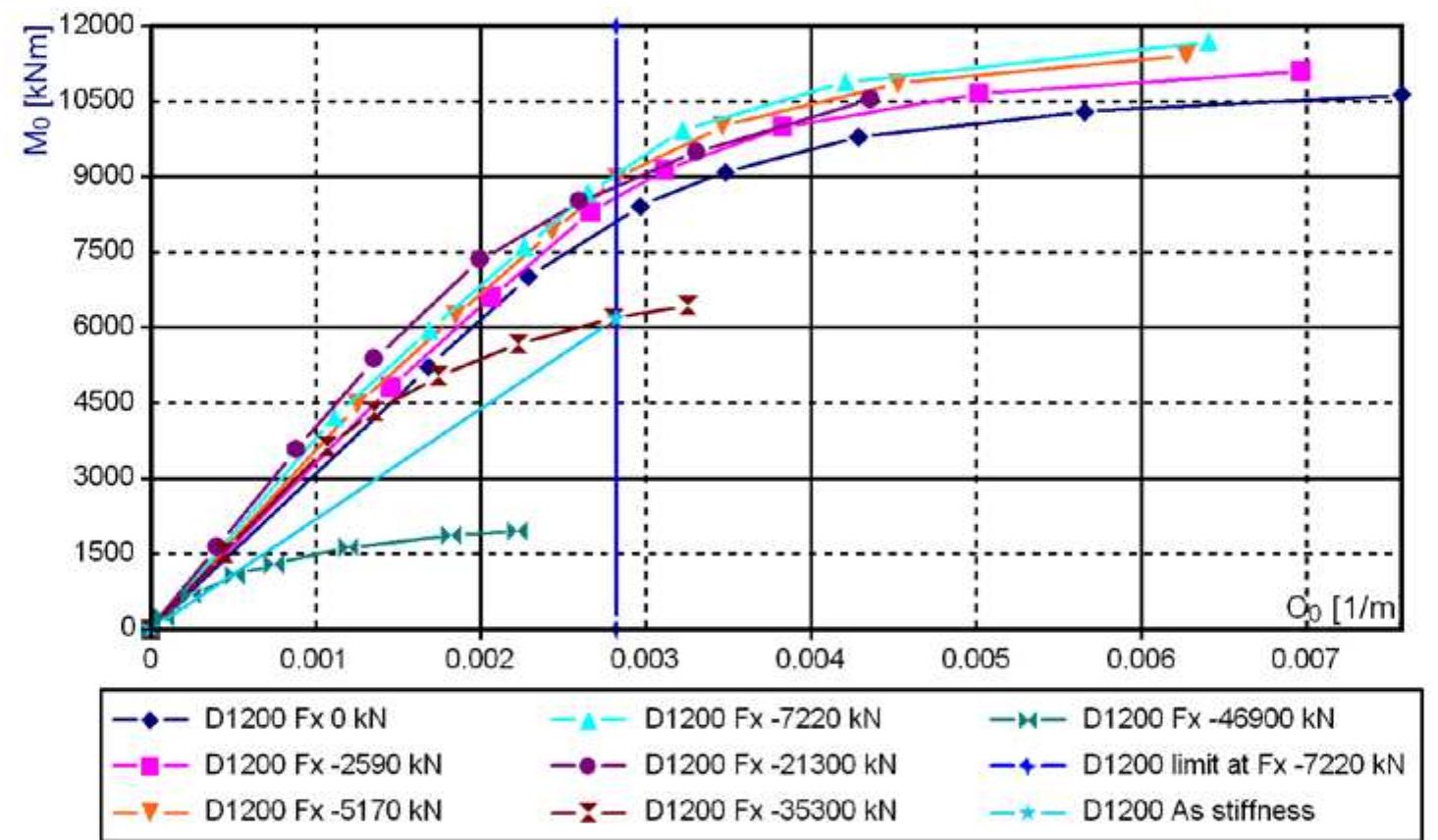

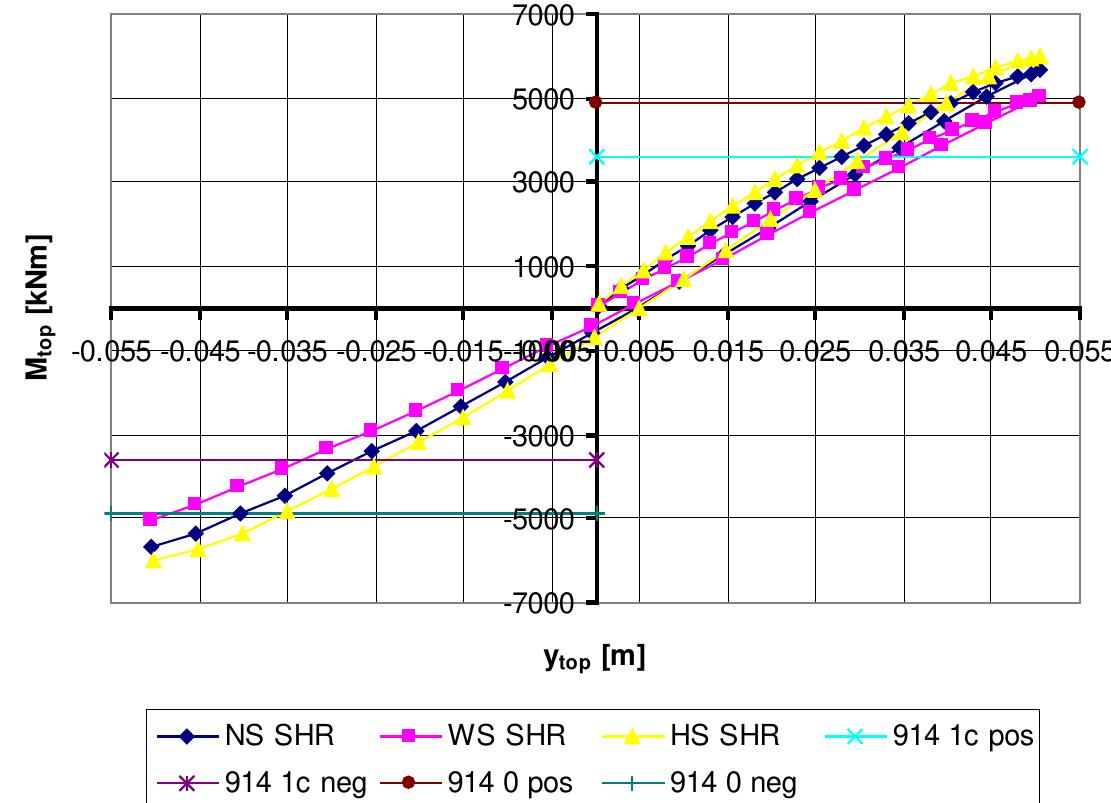

Anssi Laaksonen: Structural Behaviour of Long Concrete Integral Bridges 204 p. + 61 p. app. There are more than 20,000 bridges in Finland, of which about 2000 with a sum of span lengths over 20m are actual integral abutment road bridges. The lower building and maintenance costs of integral abutment bridges compared to conventional abutment bridges have increased interest for the former. This study deals with the structural behaviour of long concrete integral abutment bridges. The bridge subtype was limited to fully integral abutment bridges without any bearings or expansion joints. This study examines structural behaviour from the viewpoint of a bridge designer taking into consideration the effects of soil-structure interaction. It is a part of larger research project called "Soil-Bridge Structure Interaction". The main goal was to determine the effects of different soil properties at opposite bridge ends on the structural behaviour of fully integral bridges Another important goal was to determine the maximum allowable total thermal expansion length of a fully integral concrete bridge in terms of structural behaviour of piles at the bridge ends at the climatic conditions of monitored bridges. A further goal was to give suggestions for constructing integral bridges together with the whole research team. Three bridges, Haavistonjoki Bridge, Myllypuro Overpass and Tekemäjärvenoja Bridge, were monitored during this study. The main focus of the monitoring was the Haavistonjoki Bridge. The instrumentation of Haavistonjoki Bridge on the Tampere-Jyväskylä highway was completed in autumn 2003. Monitoring data have been collected by a total of 191 gauges, of which 98 are still working seven years after the monitoring started. The instrumentation is used to measure longitudinal abutment movements, abutment rotations, earth pressure behind abutments, superstructure displacements, frost depth, air temperature, and temperature differences in superstructure and approach embankment. The method for calculating uniform bridge superstructure temperature based on ambient temperature was developed on the basis of monitoring results from the Haavistonjoki Bridge. The temperature was calculated backwards until 1959 with this method. Obtained results correlate very well with the temperature loads of Eurocode EN 1991-1-5. Structural analyses were run on single laterally loaded composite piles and a whole bridge structure using software based on the finite element method. The analyses on single com-8.3.

Figures (401)

![Figure 1.3. (a) & (b) frame abutments, (c) embedded abutment, (d) bank pad abutment, (e) & (f) end screen abutments. Integral bridge abutment types according to [137]. not discussed here.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_004.jpg)

![bridge monitoring projects form the core of this comprehensive research. abutment bridges was completed in 2006 [75]. A railway bridge oriented dissertation was](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_006.jpg)

![Figure 2.1. Lateral subgrade reaction of pile in cohesionless soil. Notations as in Paragraphs 2.2.4 and 6.3.4 [43, 79]. where strains exceed the yield point.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_008.jpg)

![Figure 2.2. “Development of passive earth pressure of non-cohesive soils versus normalised wall displace- ment v/v,”[121].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_009.jpg)

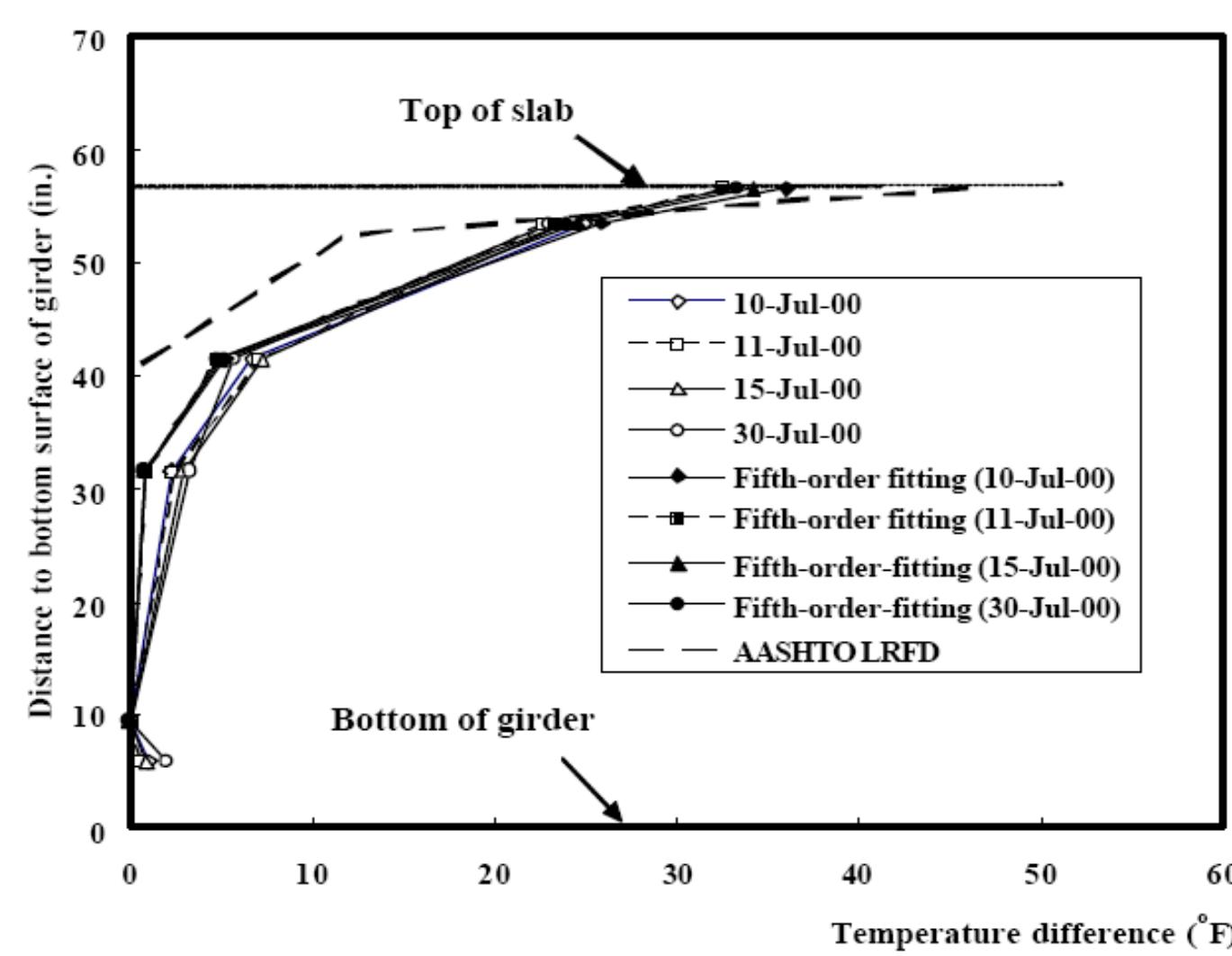

![‘igure 2.3. Superstructure temperature components [116]. Here, the temperature field is divided in four parts. The most significant part in terms of](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_010.jpg)

![Figure 2.4. Superstructure uniform temperature range Te min aNd Te max [°C] [116]. in [116] have to be used. The range of the superstructure uniform temperature is presented](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_011.jpg)

![integral bridges. Figure 2.5 presents a stub-type abutment according to [2]. or an abutment will be 0.05 m [140]. The suggested limit would lead to relatively lon;](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_012.jpg)

![Figure 2.6. HP pile orientations in US Practice [106]. 2.6 are oriented for the weak axis. Displacement of 1% of end screen height is required to reach full passive earth pressure](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_013.jpg)

![Figure 2.8. The allowable pile load for a fixed (on left) and a pinned (on right) head in dense sand when bending is about the weak axis. The steel grade yield stress is 50ksi = 345MPa. [94].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_015.jpg)

![Figure 2.9. Environmental factors that affect bridge temperature according to [68].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_016.jpg)

![bridge is smaller than that of a concrete bridge. Figure 2.10. Daily ambient air temperature in Fairbanks, Alaska, USA [68].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_017.jpg)

![Figure 2.11. Effective bridge temperature (EBT) as a function of time. Seasonal and diurnal variations for bridge superstructure are shown [31]. In this dissertation EBT is the uniform temperature, Ty. superstructure. changes take a few days to develop due to the quite big specific heat capacity of a bridg uitable term than daily or diurnal fluctuation because significant uniform temperatur sented by certain fractiles which have a specific recurrence time according to presen](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_018.jpg)

![Figure 2.13. Earth pressure behind end screen as function of end screen displacement. Bridge No.203 [107]. smaller. The weekly and diurnal behaviour of earth pressure is also shown.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_020.jpg)

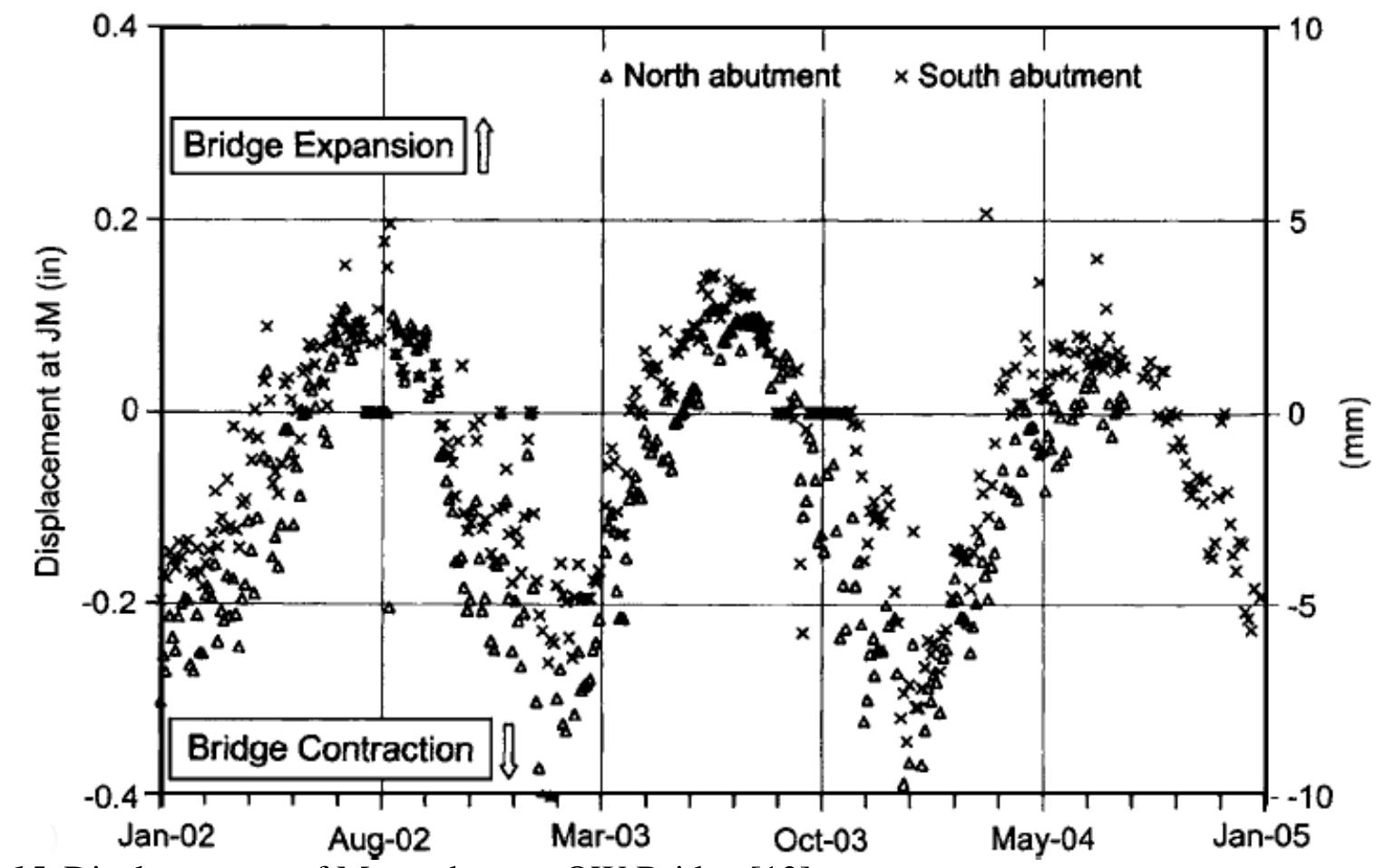

![thermal expansion length is 83.7 m. JS state of Massachusetts was monitored from 2002 on [13]. The composite bridge's total](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_021.jpg)

![the embankment which allows a small displacement to cause high earth pressure [58]. Figure 2.17. Earth pressure behind abutment in Scotch Road Bridge [58]. high. Yet, the highest earth pressure was measured in winter. This is due to the freezing of](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_024.jpg)

![Figure 2.18. Average bending moments of supporting piles of Scotch Road Bridge in June-July. The values were calculated by the LPILE program. [59]. moments of the supporting piles in June-July are presented in Figure 2.18. The bending moments are distributed along the pile length. The biggest bending moments](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_025.jpg)

![Aug-96 Aug-99 Aug-02 Aug-05 Aug-08 Aug-11 Aug-14 Aug-17 Aug-20 Aug-23 Aug-26 Figure 2.21. Tendencies of computed and measured pile curvatures [66].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_028.jpg)

![Figure 2.23. Idealised strain on supporting piles as function of time ina fully integral bridge [3, 26]. tegral abutment is presented in Figure 2.23 [3, 26].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_030.jpg)

![By introducing a dimensionless variable, written [133, 104]: ited along depth (see Figure 6.18a) and q = 0, the following differential equation can be](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_032.jpg)

![Figure. 2.25. Power functions of modulus of lateral subgrade reaction [95]. soils are presented in Figure 2.25. Power functions and distributions of modulus of lateral subgrade reaction in cohesionles: 141]. The solutions require series development. Solutions for cases where the modulus of](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_033.jpg)

![Figure 2.26. Comparison of moment values of different distributions of modulus of lateral subgrade reaction [95]. Pile has hinged top connection. Loading is a lateral force on top of pile. On the left, unitless moment values; on the right, distributions of modulus of lateral subgrade reaction. distributions of the modulus of lateral subgrade reaction are presented in Figure 2.26.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_034.jpg)

![Figure 2.27. Force-displacement relationship of pile-soil-interaction, for terms see Formula 2.25 [20]. reaction is presented in Figure 2.27. infinite length. A general hyperbolic force-displacement relationship of lateral subgrade stiffness and ultimate resistance affect the force-displacement relationship along different](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_035.jpg)

![Figure 2.28. Hyperbolic stress— strain relationship with scaling parameter Ry. The figure is based on [123] [he hyperbolic stress-strain relationship with scaling parameter R¢ is presented in Figure](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_036.jpg)

![Figure 2.29. Influence of Pile Diameter on Dimensions of Bulb Pressure [129]. presented in Figure 2.29. aviour has been continuum bulb pressure. That pressure at two different pile diameters is](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_037.jpg)

![Figure 2.30. Distribution of front earth pressure and side shear around pile subjected to lateral load [125].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_038.jpg)

![Figure 2.31. Effect of pile cross section on q-y curve [9]. Loose sand ¢ = 30° and dense sand od = 40°. [75]. The shape of the pile cross section also affects lateral behaviour [9].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_039.jpg)

![Figure 2.32. Hysteretic backbone curve [130].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_040.jpg)

![Figure 2.34. a) Soil-pile superstructure model b) variation in q-y curves along depth [97].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_042.jpg)

![elasto-plastic springs in [97], see Figure 2.35. The solution consists of several springs connected to the same node. The method allows](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_043.jpg)

![Figure 2.37. Hysteresis loops of q-y with components of different pile sides [4]. teresis loops of different sides of a pile are presented in Figure 2.37.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_045.jpg)

![Figure 2.38. Effect of fully integral bridge end rotations on pile curvatures [66]. piles, see Figure 2.38. rotations. Rotation of the bridge end screen decreases the curvature of the top of supporting](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_046.jpg)

![Figure 2.39. Soil-structure interaction behaviour of a single-span fully integral bridge under live load [29]. tion, and the superstructure is displaced under the live load.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_047.jpg)

![Figure 2.40. Soil-structure interaction behaviour of a three-span integral bridge under live load [27].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_048.jpg)

![Figure 2.41, Massachusetts OW Bridge abutment and approach slab details [22]. porting piles are subjected to smaller strains from temperature and live loads. tion of a predrilled hole is to reduce the modulus of lateral subgrade reaction when sup-](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_049.jpg)

![Figure 2.42. Calculated effects of predrilled holes on pile curvature at falling uniform temperature 27.8°C for the 66.9 m total expansion length. On the left stiff clay, on the right very stiff clay [66].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_050.jpg)

![2.43 [66]. Here, the pile head is treated as a partly hinged connection with limited hinge](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_051.jpg)

![Figure 2.44. Abutment with hinged support at top of pile [25].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_052.jpg)

![of end screen displacement gauges are presented in Figure 4.3. TUT so that they measured earth pressures accurately and were durable [84]. The locations sliding gauges during check surveys. The devices are placed so that end screen rotation](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_055.jpg)

![Figure 5.26. Speed of loading vehicle, change of earth pressure between end screen and embankment at EPC K and displacement of superstructure at measurement location 10 of abutment T4 in the braking test. and the 500 KN braking force for this type of bridge was given in the guidelines [42]. The braking force induced a longitudinal displacement in the superstructure against abut- The developed force was rather significant compared to the mass of the loading vehicle,](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_092.jpg)

![Table 5.2. Calculated and measured extreme Ty values during the four-year monitoring period [°C]. Monitor- ing year changes on 10" of October. *) Compared at time when monitoring devices were measuring properly and Ty was not at its lowest.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_005.jpg)

![Figure 5.41. Calculated annual extreme values of Ty from 1959 to 2007 as function of annual extreme values of ambient air temperature and Ty values according to Eurocode [102].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_107.jpg)

![Figure 5.43. Earth pressure-displacement relation between end screen and embankment as measured and presented in Finnish guidelines [46].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_109.jpg)

![Figure 6.4. Strain stages for capacity calculations of composite pile cross section. Strain unit is [%o]. Tension is positive. -2 %o and -3.5 %o at the edge of the cross section with normal strength (fex.cube < 60 MN/m‘’)](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_113.jpg)

![*) Cross section dimensions in Finnish manufacturing are D*t = 1219*16 Table 6.2. Composite cross section capacity with component N [kN] and M [kNm] No,opt2 18 calculated with the simplified formula:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_007.jpg)

![behaviour. Four different types of distribution are presented in Figure 6.18. Figure 6.18 a)-d) Linear, constant, parabolically distributed modulus of lateral subgrade reaction according to Finnish guidelines [43]. In the Figure the pile is rotationally supported from the top of pile. The distribution of modulus of lateral subgrade reaction affects the laterally loaded pile](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_127.jpg)

![Table 6.5. Distances s [m], according to Figures 6.18 and 6.19 moment develops at the top of pile:](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_010.jpg)

![Table 6.6. Displacement capacities [m] of yjop at Do with Nop: in T1_R- and T2_Rmodels](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_011.jpg)

![are presented in Figure 6.36. composite cross section), Table 6.5 (values of s) and Table 6.6 (displacement capacity of length in the EXP models are higher than in the SHR models and in the T2 than in the T]](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_145.jpg)

![Table 6.7. Equivalent modified constant of lateral subgrade reaction m,-, when modulus of subgrade reactior is linearly distributed along pile length [MN/m°] Values Of Mheq are almost independent of pile diameter in terms of bending moments partly](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_012.jpg)

![Table 6.8. The selection of structural heights ha was based on existing bridges and reference [37]. Th](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_013.jpg)

![Figure 6.41. Balancing of uniform load, in the figure: Fy, = Fy, [90, 91]. slightly upwards. This kind of load-balancing method is presented in [90, 91]. of spans from combined displacement from permanent load and post-tensioning force was](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/figure_150.jpg)

![Table 6.12. Strains and equivalent temperature drops The shrinkage strain €¢ snr of concrete is set to -0.00025 [-] [35, 45]. Then the equivalen perature drop values and corresponding strains are presented in Table 6.12. drop ATmoa, which is the equivalent temperature drop AT.g multiplied with mg. The tem- has been applied. The discussed loads were assigned to the FE model with temperatur](https://figures.academia-assets.com/103679042/table_017.jpg)

Related papers

Structural Engineering International, 2011

One of the most commonly discussed problems regarding bridges with integral abutments is the influence of longitudinal elongation of the superstructure as a result of seasonal temperature variations. A bridge built with integral abutments is often supported by a row of piles made of steel or concrete. The longitudinal elongation of the superstructure induces a displacement and a rotation at the top of the pile, which in turn may cause strains that exceeds the yield strain. Such seasonal variations may lead to low-cyclic fatigue failure in the pile. Therefore, it is of great interest to investigate the amplitude of these strains, as well as the general behaviour of the bridge. In 2005, the European R&D project, INTAB (RFSR-CT-2005-00041, "Economic and Durable Design of Bridges with Integral Abutments, 2005-2008") was started. Within the INTAB project a composite bridge was built and monitored in Northern Sweden.

Composite Construction in Steel and Concrete VI, 2011

One of issues that have not been completely resolved in bridges built without expansion joints is an influence of seasonal temperature variations and soil characteristics on the maximum bridge length. A 40 meter long road composite bridge over river Leduån in the north of Sweden was built in 2005. The bridge superstructure was cast integrally with the substructure. One row of pile on each side of the bridge was constructed to support the abutment. The bridge was continually monitored 18 months in order to provide information on the strain level at the top of the pile as a function of the air temperature variations. The result from the measurements were compared to results obtained in 2D Finite Element Analysis. Soil characteristics were varied in the FEA to investigate its influence on the overall bridge behaviour as well as on the level of strain variations at the top of the piles. The bridge monitoring was a part of a research project, INTAB, Economic and Durable Design of Composite Bridges with Integral Abutments, 2005-2008. The main objective of the project was to propose recommendations for rational analysis and design of bridges with integral abutments. The total environmental impact and the life cycle costs of the integral abutment bridge were compared with a concrete bridge alternative for the same crossing.

Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Smart Infrastructure and Construction

This paper gives an overview of almost 3 years of monitoring data obtained from instrumentation installed in a 90 m long reinforced concrete integral bridge in South Africa. The main objective of this structural monitoring project was to assess the effect of environmental factors on integral bridge abutment movement, with specific focus on thermal effects. The data obtained from the instrumentation enable designers to compare real and assumed effective bridge deck temperatures, earth pressures and abutment movements. Analysis of the data seems to indicate that the deck cross-sectional shape (defined as the ratio of surface area to the cross-sectional area) has a significant effect on the effective bridge deck temperature, abutment movement and earth pressure.

2007

Preliminary results obtained from short term test-loading are used to illustrate possibilities of FEM used to calibrate complex interaction characteristics between a pile and soil in a bridge with integral abutments. The measurements are obtained during the winter season on the bridge over Ledån, Northern Sweden. The bridge is built in 2006 and used for long term monitoring within the international project supported by RFCS. The main objective of the ongoing research project is to proposed recommendations for rational analysis and design of bridges with integral abutments.

2019

This paper gives an overview of almost three years of monitoring data obtained from instrumentation installed in a 90m long reinforced concrete integral bridge in South Africa. The main objective of this structural health monitoring project was to assess the effect of environmental factors on integral bridge abutment movement, with specific focus on thermal effects. The data obtained from the instrumentation enables designers to compare real and assumed effective bridge deck temperature, earth pressure and abutment movement. Analysis of the data seems to indicate that the deck cross section shape (defined as the ratio of surface area to cross sectional area) has a significant effect on the effective bridge temperature, abutment movement and earth pressure. This hypothesis was tested using the preliminary SHM data, and conclusions were drawn as to whether an increase in deck thermal inertia might be used to mitigate the effects of increased deck length.

Advanced Materials Research, 2012

Structural behavior of concrete integral abutment bridge subjected to temperature rise was investigated through a numerical modeling and parametric study. Long-term, field monitoring through the summer was performed on Industrial Park Bridge located in Heilongjiang province, China from June 13, 2010 until June 28, 2010. The collected data was used to validate the accuracy of a 3D-finite element model of the bridge which took into account soil-structure interaction. Based on the calibrated finite element model a parametric study considered two parameters, bridge length and abutment height, was carried out to investigate the effects of this parameters on structural behavior of integral abutment bridge subject to temperature rise. It was determined that Thermal load in the superstructure of the integral bridge develop significant magnitudes of bending and axial forces in the superstructure. The largest magnitude of thermally induced moment always occurs near the abutment, and axial for...

Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures

Bridges are one of the most critical parts of transportation networks that may suffer damages against earthquakes. Also, seismic responses of most bridges are significantly influenced by soil-structure interaction effects. Taking out expansion joints in the bridges may cause many difficulties in design and analysis due to the complexity of soil-structure interaction and nonlinear behavior. The secondary loads on an IAB include seismic load, temperature variation, creep, shrinkage, backfill pressure on back wall and abutment, all of which cause superstructure length and stress variations in girder changes. The purpose of this study is to recognize the most effective parameters of analysis IABs. Findings show that the backfill material behind the IABs has a significant effect on the performance of IABs. Using a compressible material behind the abutments would enhance the in-service performance of IABs. Finally, behaviour of abutment may be greatly affected by thermal load and soil pressure. Thermal expansion coefficient significantly influences girder axial force, girder bending moment, and pile head/abutment displacement.

2006

Page 66: … cell) increased 0.59 kN/m 2 while the deck moved 0.55 mm against the embankment. => … cell) decreased 0.59 kN/m 2 while the deck moved 0.55 mm against the opposite embankment. Page 132: Kerokoski, Olli. 2005 a. Soil-structure interaction of jointless bridges. Literarture research. => Kerokoski, Olli. 2005 a. Soil-structure interaction of jointless bridges. Literature research.

International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research

Integral Abutment bridges (IAB's) can be defined as bridges without joints. The main purpose of constructing IAB's is to pre-vent the corrosion of the structure due to water seepage through joints. The biggest uncertainty in the design of these bridges is the re-action of the soil behind the abutments and next to the foundation piles, especially during thermal expansion. This lateral soil reaction is nonlinear and is a function of the magnitude and nature of the wall displacement.To gain a better understanding of the mechanism of load transfer due to thermal expansion, which is also dependent on the type of the soil adjacent to the abutment walls and piles, a 3D fi-nite element analysis is carried out on representative IAB. In this paper two models are compared one with considering soil interaction and other without soil interaction and live load is applied using STAAD-Beava. The main objective is to study the trends in bending mo-ment, shear force and deflection in central ...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (149)

- AASHTO. 1989. AASHTO Guide Specifications -Thermal Effects in Concrete Bridge Superstructures. Washington, D.C. 60 p.

- AASHTO. 2007. AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications, SI units, 4th Edition. Washington, D.C. pp. 3-99 -3-104.

- Abhasai, S & Dicleli, M. 2004. Effect of cyclic thermal loading on the perform- ance of steel H-piles in integral bridges with stub-abutments. Journal of Con- structional Steel Research. Vol. 60, No. 2., pp. 161-182.

- Allotey, N. & El Naggar, M. H. 2008. Generalized dynamic Winkler model for nonlinear soil-structure interaction analysis. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 560-573.

- Arsoy, S. 2000. Experimental and Analytical Investigations of Piles and Abut- ments of Integral Bridges. Dissertation. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 186 p. + 59 app. p.

- Arsoy, S. et al. 2002. Experimental and Analytical Investigations of Piles and Abutments of Integral Bridges. Virginia Transportation Research Council. Report No. FHWANTRC 02-CR6. 55 p.

- Ashford, S. & Juirnarongrit, T. 2003. Evaluation of Pile Diameter Effect on Ini- tial Modulus of Subgrade Reaction. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvi- ronmental Engineering. Vol. 129, No. 3., pp. 234-242.

- Ashford, S. 2005. Effect of the pile diameter on the modulus of subgrade reac- tion. Publication number SSRP-2001/22, University of California, San Diego. 322 p. + 32 app. p. ISBN 952-15-1620-8.

- Ashour, M. & Norris, G. 2000. Modeling Lateral Soil-Pile Response Based on Soil-Pile Interaction. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engi- neering. Vol. 126, No. 5., pp. 420-428.

- Bouafia, A. 2007. Single piles under horizontal loads in sand: determination of P-Y curves from the prebored pressuremeter test. Geotechnical and Geologi- cal Engineering. Vol. 25, No. 3., pp. 283-301.

- Bowles, J.E. 1982. Foundation Analysis and Design, Chapter 16. pp. 867-968. ISBN 0-07-118844-4

- Branco, F. & Mendes, P. 1993. Thermal Actions for Concrete Bridge Design. Journal of Structural Engineering. Vol. 119, No. 8, pp. 2313-2331.

- Brena, S. & Bonczar, C. et al. 2007. Evaluation of Seasonal and Yearly Behav- iour of an Integral Abutment Bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 12, No. 3., pp. 296-305.

- Briaud, J. L. et al. 1984. Laterally loaded piles and the pressuremeter: Compari- son of existing methods. Laterally Loaded Deep Foundations, ASTM STP 835, ASTM, West Conshohocken. pp. 97-111.

- Broms, B. 1976. Geoteknik, Kompendium Del IV. Kungliga Tekniska Högsko- lan (Royal Institute of Technology), Stockholm. 92 p. (In Swedish)

- Budkowska, B. & Szymczak, C. 1995. On first variation of extremum values of displacements and internal forces of laterally loaded piles. Computer & Structures. Vol. 57. No. 2. pp. 303-307.

- Byung, T.K. et al. 2004. Experimental Load-Transfer Curves of Laterally Loaded Piles in Nak-Dong River Sand. Journal of Geotechnical and Geo- environmental Engineering. Vol. 130, No. 4., pp. 416-425.

- Carder, D. et al. 2002. Suitability testing of materials to absorb lateral stresses behind integral bridge abutments. Publication number TRL552, Transport Research Laboratory. 48 p. + 4 app. p. ISSN 0968-4107.

- Carter, D.P. 1984. A Non-linear Soil Model for predicting lateral pile response. Master's thesis. THESIS 1984-C24. University of Auckland.

- Castelli, F. 2002. Discussion of ''Response of Laterally Loaded Large- Diameter Bored Pile Groups'' by Charles W. W. Ng, Limin Zhang, and Dora C. N. Nip. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 128, No. 11., pp. 963-964.

- Chakrabarti, A. et al. 2009. Lateral load capacity estimation of large diameter bored piles and its implementation: a study. IABSE reports = Rapports AIPC = IVBH Berichte, Vol.80 (1999).

- Civjan, S. & Bonczar, C. et al. 2007. Integral Abutment Bridge Behavior: Pa- rametric Analysis of a Massachusetts Bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 12, No. 1., pp. 64-71.

- Clayton, C. & Bloodworth, A. 2006. A laboratory study of the development of earth pressure behind integral bridge abutments. Géotechnique. Vol. 56, No.

- Concrete association of Finland. 1984. Suunnittelun sovellusohjeet, BY 16 (Application note of concrete design). Jyväskylä. 283 p. + 101 app. p. ISBN 951-9365-17-6. (In Finnish)

- Connal, J. 2004. Integral Abutment Bridges -Australian and US Practice. Aus- troads 5th Bridge Conference, Hobart, Australia, May 19-21. 19 p.

- Dicleli, M. & Abhasai, S. 2003. Maximum length of integral bridges supported on steel H-piles driven in sand. Engineering structures. Vol. 25, No. 12. pp. 1491-1504.

- Dicleli, M. & Ehran, S. 2010. Effect of Soil-Bridge Interaction on the Magni- tude of Internal Forces in Integral Abutment Bridge Components due to Live Load Effects. Engineering Structures. Vol. 32, No. 1., pp. 129-145.

- Dicleli, M. 2000. Simplified model for computer-aided analysis of integral bridges. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 5, No. 3., pp. 240-248.

- Dicleli, M. 2008. Effect of Soil and Substructure Properties on Live-Load Dis- tribution in Integral Abutment Bridges. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 13, No. 5., pp. 527-539.

- Duncan, J.M. & Chang, C. 1970. Nonlinear Analysis of Stress and Strain in Soils. Journal of the soil mechanics and foundations division, ASCE. Vol. 96, No. 5., pp. 1629-1653.

- England, G et al. 2000. Integral Bridges; A fundamental approach to the time- temperature loading problem. 129 p. + 23 app. p. ISBN 0-7277-2845-8.

- Federal Highway Administration. 2005. The 2005 -FHWA Conference, Inte- gral Abutment and Jointless Bridges (IAJB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, United States 16-18 March. 343 p.

- Fennema, J. et al. 2005. Predicted and Measured Response of an Integral Abutment Bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 10, No. 6., pp. 666- 677.

- Finnish environmental administration. 1993-2007. Suomen rakentamismääräy- skokoelma, Rakenteiden lujuus, osa B (The National Building Code of Finland, The Strength of Structures. RakMk, part B, in Finnish)

- Finnish environmental administration. 2004. Suomen rakentamismääräy- skokoelma, rakenteiden lujuus, osa B4 Betonirakenteet (The National Build- ing Code of Finland, The Strength of Structures, part B4 Concrete Struc- tures). Helsinki.83 p. (In Finnish)

- Finnish Association of Civil Engineers. 1989. RIL 179-1989, Sillat (RIL 179- 1989, Bridges). Helsinki. 390 p. ISSN 0356-9403. (In Finnish)

- Finnish Meteorological Institute. 2002. Climatological statistics of Finland 1971-2000. Helsinki.99 p. ISSN 1458-4530. (In Finnish)

- Finnish Meteorological Institute. 2007. Statistic from Finnish climate, ambient air temperature. Published in the Internet on 5.10.2007 http://www.fmi.fi/saa/tilastot.html

- Finnish Railway Administration. 1997. Rautatiesiltojen suunnitteluohjeet, RSO, osa 4. (Railway bridge design introductions, RSO, part 4.) VR 2753.11.0, 17 p. (In Finnish)

- Finnish Transport Agency. 2010. Interviews of bridge experts of bridge engi- neering.

- Finnra. 1992-2007. Siltojen suunnitelmat (Designs of bridges). Internet 19.2.2008: http://alk.tiehallinto.fi/sillat/suunnit1.htm (In Finnish)

- Finnra. 1999. Siltojen kuormat (Loads of bridges). Helsinki. 31 p. ISBN 951- 726-538-2. (In Finnish)

- Finnra. 2000. Steel pipe piles. Helsinki. 81 p. + 3 app.p. ISBN 951-726-617-0.

- Finnra. 2005. Siltojen ylläpito, Toimintalinjat (Bridge Maintenance, manage- ment policies). Helsinki. 28 p. + 10 app.p. ISBN 951-803-461-3. (In Finnish)

- Finnra. 2006. Betonirakenteiden suunnitteluohjeet (Instructions for concrete structures). Helsinki. 33 p.. ISBN 951-803-580-6. (In Finnish)

- Finnra. 2007. Sillan geotekniset suunnitteluperusteet (Geotechnical design re- quirements for bridges). Helsinki. 50 p. + 40 app. p. ISBN 978-951-803-896- 5.

- Finnra. 2008. Siltarekisteri (Bridge register). Compiled from bridge register on 2.4.2008.

- Finnra. 2008. Sillansuunnittelun täydentävät ohjeet (Supplementary bridge de- sign instructions). Helsinki. 28 p. + 84 app. p. ISBN 978-952-221-035-7. (In Finnish)

- Finnra. 2010. Sillat 1.1.2010, Liikenneviraston sillaston rakenne, palvelutaso ja kunto (Bridges of Finnish Road Administration on 1.1.2010: structure, ser- vice level and condition of the bridge stock). Helsinki. 77 p. + 2 app. p. ISSN 1459-1561. (In Finnish)

- Frank, R. 2008. Design of pile foundations following Eurocode 7-Section 7. Presentation in workshop "Eurocodes: background and applications" Brus- sels, 18-20 February 2008. 8-13. 29 p.

- Gabr, M.A. et al. 1997. Buckling of Piles with General Power Distribution of Lateral Subgrade Reaction. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 123, No. 2., pp. 123-130.

- Gerolymos, N. et al. 2009. Numerical modeling of centrifuge cyclic lateral pile load experiments. Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration. Vol. 8, No. 1., pp. 61-76.

- Girton, D. et al. 1989. Validation of design recommendations for integral- abutment piles. Publication number HR-292, Iowa State University. 82 p. + 15 app. p.

- Greimann, L. & Wolde-Tinsae, A. 1988. Design Model for Piles in Jointless Bridges. Journal of Structural Engineering. Vol. 114, No. 6, pp. 1354-1371.

- Guo, W. 2009. Nonlinear response of laterally loaded piles and pile groups. In- ternational Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics. Vol. 33, No. 5., pp. 879-914.

- Hällmark, R. 2006. Low-cycle Fatigue of Steel Piles in Integral Abutment Bridges. Master's thesis. Luleå University of Technology. 132 p. + 39 app. p. ISSN 1402-1617.

- Han, J. & Frost, J. 2000. Load defection response of transversely isotropic piles under lateral loads. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics. Vol. 24, No. 5., pp. 509-529.

- Hassiotis, S. & Xiong, K. 2007. Deformation of Cohesionless Fill Due to Cy- clic Loading. Stevens Institute of Technology, New York. 83 p. SPR ID# C- 05-03.

- Hassiotis, S. 2007. Data gathering and design details of an integral abutment bridge. Presentation in: 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of ASCE, Blacksburg, Virginia, United States, 3-6 June pp. (EMD2007).

- Heinisuo, M. 1989. Paalun analysointi kotimikrolla (Pile analysis using a per- sonal computer). Journal of structural mechanics. Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 23-41. (In Finnish)

- Helsinki University of Technology. Course material 43.3110, Construct of Concrete Structures. 2009.

- Hetenyi, M. 1946, renewed 1974. Beams on elastic foundation. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 255 p. ISBN 0-472-08445-3

- Hettler, A. 1986. Sekantenmoduln bei horizontal belasteten Pfählen in Sand be- rechnet aus nicht-linearer Bettungstheorie. Geotechnik. Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 20- 29.

- Hilmi, M. 2002. Viscoelastic Behaviour of Composite Piles Used in the Con- struction of Quays. Turkish Journal of Engineering & Environmental Sci- ences. Vol. 26, No. 5., pp. 419-427.

- Hoppe, E. 2005. Field study of integral backwall with elastic inclusion. Publica- tion number VTRC 05-R28, Virginia Transportation Research Council. 27 p. + 10 app.p.

- Huang, J. et al. 2004. Behavior of Concrete Integral Abutment Bridges. Univer- sity of Minnesota. 294 p. + 55 app. p. MN/RC -2004-43.

- Hulsey, L. 1992. Bridge lengths: Jointless prestressed girder bridges. University of Alaska Fairbanks. Final report No. INE/TRC/GRP-92.04. 36 p. + 22 app. p.

- Hulsey, L. et al. 1990. The no expansion joint bridge for northern regions. Uni- versity of Alaska Fairbanks. Final report No. INE/TRC 90.02. 163 p. + 25 app. p.

- Hyrkkönen, A. 1988. Geotechnical bearing capacity of large steel pipe pile. Master's thesis. Tampere University of Technology 187 p. (In Finnish)

- Järvinen P. & Järvinen A. 1996. Tutkimustyön metodeista (On Research Met- hods). Tampere University. ISBN 951-97113-1-7. (In Finnish)

- Järvinen, V. 2010. Sillansuunnittelun perusteet (Basics of bridge engineering), RTEK-3610. Tampere University of Technology. 89 p. (In Finnish)

- Kagawa, T., and Kraft, L. (1980). Seismic P-Y Responses of Flexible Piles. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering. Vol. 106, No. 8, pp. 899-918.

- Kerokoski, O. 2005. Soil-structure interaction of jointless bridges. Literature research. Tampere University of Technology. 150 p. ISBN 952-15-1352-7. (In Finnish)

- Kerokoski, O. 2005. Soil-structure interaction of jointless bridges with integral abutments. Calculations. Tampere University of Technology. 126 p. Internet 19.2.2008: http://alk.tiehallinto.fi/sillat/julkaisut/silta_ja_maa_lask_06.pdf (In Finnish)

- Kerokoski, O. 2006. Soil-Structure Interaction of Long Jointless Bridges with Integral Abutments. Dissertation. Publication number 605, Tampere Univer- sity of Technology 136 p. + 30 app. p. ISBN 952-15-1620-8.F

- Khodair, Y. & Hassiotis, S. 2005. Analysis of soil-pile interaction in integral abutment. Computers and Geotechnics. Vol 32, No 3. pp. 201-209.

- Klug, P. & Wittmann, F. 1970. The correlation between creep deformation and stress relaxation in concrete. Materials and Structures. Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 75- 80.

- Koskinen, M. 1997. Composite action of steel pipe pile. Publication number 45, Tampere University of Technology. 27 p. ISBN 951-722-989-5.

- Koskinen, M. 1997. Horizontal capacity of steel pipe pile. Licentiate thesis. Tampere University of Technology. 204 p. + 27 app. p. (In Finnish)

- Koskinen, M. 1997. Soil-Structure Interaction of Jointless Bridges on Piles. Dissertation. Publication number 200, Tampere University of Technology. 184 p. ISBN 951-722-741-8.

- Küçükarslan, S. et al. 2003. Inelastic analysis of pile soil structure interaction. Engineering structures. Vol. 25, No. 9. pp. 1231-1239.

- Kumar, S. et al. 2006. Nonlinear response of single piles in sand subjected to lateral loads using k hmax approach. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering. Vol. 24, No. 1., pp. 163-181.

- Laaksonen, A. & Kerokoski, O. 2007. Long-term Monitoring of Haavistonjoki Bridge. IABSE Symposium, Weimar, Germany. pp. 360-361.

- Laaksonen, A. 2004. Soil-structure Interaction of Jointless Bridges. Master's thesis. Tampere University of Technology 160 p. + 76 app. p. ISBN 952-15- 1338-1. (In Finnish)

- Laaksonen, A. 2005. Field Test of Tekemäjärvenoja Railway Bridge. Research report. Tampere University of Technology, Earth and Foundation Structures. 25.3.2008, unpublished. Available from Unit of Earth and Foundation Struc- tures TUT. (In Finnish)

- Laaksonen, A. 2008. Soil-structure interaction of integral bridge: Test loading with mobile crane. Tampere University of Technology, Earth and Founda- tion Structures. 69 p. + 11 app. p. Published on the Internet, 27.3.2008: http://www.tut.fi/units/rka/mpr/julkaisut/silta_ja_maa_koekuorm.pdf

- Lawrer, A. et al. 2000. Field performance of integral abutment bridge. Trans- portation Research Record 1740, paper No. 00-0654. pp. 108-117.

- Leppänen, M. 1992. Corrosion of steel pipe piles. Master's thesis. Tampere University of Technology 203 p + 19 app.p. (In Finnish)

- Lianyang, Z. et al. 2005. Ultimate Lateral Resistance to Piles in Cohesionless Soils. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 131, No. 1, pp. 78-83.

- Lin, T.Y. & Burns, N.H. 1981. Design of prestressed concrete structures. New York. 646 p. ISBN 0-471-01898-8.

- Lin, T.Y. 1963. Load-Balancing Method for Design and Analysis of Prestressed Concrete Structures. ACI Journal Proceedings (American Concrete Institute). Vol. 60, No. 6., pp. 719-742.

- Ling, L.F. 1988. Back analysis of lateral load test on piles. Report / University of Auckland School of Engineering 460. University of Auckland. 117 p. + 78 app. p. ISSN 0111-0136

- LUSAS. 2008. Element reference manual, LUSAS version 14.3: Issue 1. p. 69, 277 and 324.

- Maine department of transportation (MDOT). 2003. Bridge design guide: Part 5: Substructures. Updated in 2007.

- Matlock, H. & Reese, L. 1960. Generalized solutions for laterally loaded piles. Journal of the soil mechanics and foundations division, ASCE. Vol. 86, No. 5., pp. 63-91.

- Matlock, H. & Reese, L. 1961. Foundation analysis of pile supported structures. The Fifth International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engi- neering. Paris. 17-22 July. Volume II, pp. 91-97.

- Matlock, H. et al. 1979. SPASM 8 -A Dynamic Beam-Column, Program for Seismic Pile Analysis with Support Motion. Fugro, Inc.

- Meymand, P. 1998. Shaking Table Scale Model Tests of Nonlinear Soil-Pile- Superstructure Interaction In Soft Clay. University of California, Berkeley. 457 p. + 5 app. p.

- Mikkola, M. 1981. Kimmoisella alustalla oleva palkki (Beam on elastic founda- tion). Publication number 36, Helsinki University of Technology. 33 p. (In Finnish)

- Mistry, V. 2005. Integral Abutment and Jointless Bridges. The 2005 - FHWA Conference, Integral Abutment and Jointless Bridges (IAJB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, United States 16-18 March. pp. 3-11.

- Mokwa, L. 1999. Investigation of the Resistance of Pile Caps to Lateral Loading. Dissertation. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 302 p. + 80 app.p.

- NA SFS-EN 1991-1-5. 2007. Eurocode 1: Actions on structures -Part 1-5: General actions-Thermal actions. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki. 5 p.

- Oesterle, R & Volz, J. 2005. Effective temperature and longitudinal move- ment in integral abutment bridges. The 2005 -FHWA Conference, Integral Abutment and Jointless Bridges (IAJB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, United States 16-18 March. pp. 302-311.

- Ollila, M. 1973. Theorie der räumlichen Pfahlwerke im elastischen Kon- tinuum. Dissertation. Publication number TKK-DISS-278 TES 661, Helsinki University of Technology 78 p. (In German)

- Petursson, H. & Collin, P. 2002. Composite Bridges with Integral Abutments Minimizing Lifetime Cost. IABSE Symposium, Melbourne, Australia. 9 p.

- Preston, H. Plastic Design of Steel HP-Piles for Integral Abutment Bridges. The 2005 -FHWA Conference, Integral Abutment and Jointless Bridges (IAJB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, United States 16-18 March. pp. 270-280.

- Pugasap, K. 2006. Hysteresis model based prediction of integral abutment bridge behaviour. Dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University. 259 p. + 126 app. p.

- Rautaruukki Oyj. 2010. Brochure: Large diameter steel pipe piles. Hämeenlinna. 19 p. (In Finnish)

- Roberts-Wollman, C. & Breen, J. & Cawrse, J. 2002. Measurements of Thermal Gradients and their Effects on Segmental Concrete Bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering. Vol. 7, No. 3., pp. 166-174.

- Rodolfo, M. & Samer, P. 2005. Integral Abutments and Jointless Bridges (IAJB) 2004 Survey Summary. The 2005 -FHWA Conference, Integral Abutment and Jointless Bridges (IAJB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, United States 16-18 March. pp. 12-29.

- Ross, A. D. 1958. Creep of concrete under variable stress. Vol. 29, No. 9, pp. 739-758.

- Rovithis, E. et al. 2009. Experimental p-y loops for estimating seismic soil- pile interaction. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering. Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 719- 736.

- Rowe, P.W. 1956. The Single Pile Subject to Horizontal Force. Geotech- nique. Vol 6, No. 2., pp. 70-85.

- Sadrekarimi J. & Akbarzad M. 2009. Comparative Study of Methods of De- termination of Coefficient of Subgrade Reaction. The Electronic Journal of Geotechnical Engineering. Vol. 14, bundle E., pp. 419-427.

- SFS-EN 1990. Eurocode 0, Basis of structural design. Finnish Standards As- sociation, Helsinki. 138 p.

- SFS-EN 1991-1-5. 2003. Eurocode 1: Actions on structures -Part 1-5: Gen- eral actions -Thermal actions. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki. 68 p.

- SFS-EN 1991-2. Eurocode 1: Actions on structures. Part 2: Traffic loads on bridges. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki. 164 p.

- SFS-EN 1992-1-1. Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures -Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings. Finnish Standards Association, Hel- sinki.

- SFS-EN 1992-2. Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures -Part 2: Con- crete bridges. Design and detailing rules. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki.

- SFS-EN 1994-2. Eurocode 4: Design of composite steel and concrete struc- tures -Part 2: General rules and rules for bridges. Finnish Standards Asso- ciation, Helsinki.

- SFS-EN 1997-1. Eurocode 7. Geotechnical design -Part 1: General rules. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki.

- Shamsabadi, A. & Nordal, S. 2006. Modeling passive earth pressures on bridge abutments for nonlinear Seismic Soil-Structure interaction using Plaxis. Plaxis Bulletin. No. 6., pp. 8-15.

- Shamsabadi, A. et al. 2007. Nonlinear Soil-Abutment-Bridge Structure In- teraction for Seismic Performance-Based Design. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 133, No. 6., pp. 707-720.

- Shirato, M. et al. 2006. A New Nonlinear Hysteretic Rule for Winkler Type Soil-Pile Interaction Springs that Considers Loading Pattern Dependency. Soils and Foundations, Japanese Society of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering. Vol. 46, No. 2., pp. 173-188.

- Smith, T. 1987. Pile horizontal modulus values. Journal of Geotechnical En- gineering. Vol. 113, No. 9., pp. 1040-1044.

- Smoltczyk, U. 1992. Grundbau-Taschenbuch, Teil 3. 846 p. Berlin. ISBN 3- 433-01412-4 (In German)

- Stark, R.F. & Booker, J.R. 1997. Surface Displacements of a Non- homogeneous Elastic Half-space Subjected to Uniform Surface Tractions. Part II: Loading on Rectangular Shaped Areas. International Journal for Nu- merical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics. Vol. 21, No. 6., pp. 379- 395.

- Taciroglu, E. et al. 2006. A Robust Macroelement Model for Soil-Pile Inter- action under Cyclic Loads. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 132, No. 10, pp. 1304-1314.

- Terzaghi, K. 1955. Evaluation of coefficients of subgrade reaction. Geotech- nique. Vol 5, No. 4., pp. 297-326.

- Terzaghi, K. et al. Soil mechanics in engineering practice. pp.133-134. ISBN 0-471-08658-4

- The International Federation for Structural Concrete (fib). 1999. Structural Concrete. Textbook on Behaviour, Design and Performance Vol. 1: Introduction -Design Process -Materials. Stuttgart. ISBN 978-2- 88394-041-3.

- Timoshenko, S. & Goodier, J.N. 1951. Theory of Elasticity. pp. 366-372

- Titze, E. 1970. Über den seitlichen Bodenwiderstand bei Pfahlgründungen. Bauingenieur-Praxis, 77. Berlin. 118 p. + 18 app. p. ISBN 3-433-00040-9 (In German)

- Törnqvist, J. 2004. Teräsputkipaalujen korroosio, Mitoitus empiiriseen aineistoon pohjautuen (Corrosion of steel piles, dimensioning on the basis of empirical material). Espoo. 42 p. ISBN 952-5004-53-8. (In Finnish)

- Tschumi, M. 2008. Railway actions, selected chapters from EN 1991-2 and Annex A2 of EN 1990. Presentation in workshop "Eurocodes: background and applications" Brussels, 18-20 February 2008. 8-13. 37 p.

- Tuominen, M. 2008. The Utilization of Elastic Material in Integral Abutment Bridges. Master's thesis. Tampere University of Technology 67 p. + 14 app.p. (In Finnish)

- UK Highways Agency 2003. Design manual for roads and bridges, Volume 1 Section 3 Part 12 BA42/96, The Design of Integral Bridges. The Stationary Office UK. 16 p.

- Vesic, A.S. 1961. Beams on Elastic Subgrade and Winkler Hypothesis. Pro- ceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foun- dation Engineering. Paris. Vol 1, pp. 545-550.

- Vilonen, H. 2007. Soil-structure interaction of skewed jointless bridges. Mas- ter's thesis. Tampere University of Technology. 83 p. + 38 app. p. Internet 19.2.2008: http://alk.tiehallinto.fi/sillat/julkaisut/silta_ja_maa_vino.pdf (In Finnish)

- Wasserman, E. 2007. Integral abutment design (Practices in the United States). 1st U.S.-Italy Seismic Bridge Workshop, Pavia, Italy, 19-20 April. 12 p.

- Wiemann, J. et al. 2004. Evaluation of Pile Diameter Effects on Soil-Pile Stiffness. 7th German Wind Energy Conference DEWEK. Wilhelmshaven. 20-21 October. 4 p.

- Woodward, R. et al. 1972. Drilled Pier Foundations. McGraw-Hill Company. pp. 61-104. ISBN 0-07-071783-4.

- Yoshida, I. & Yoshinaka, R. 1972. A Method to Estimate Modulus of Hori- zontal Subgrade Reaction for a Pile. Soils and Foundations, Japanese Society of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering. Vol. 12, No. 3. pp. 1-17.

- Zhang, L. et al. 2005. Ultimate Lateral Resistance of Piles in Cohesionless Soils. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Vol. 131, No. 1., pp. 78-83.

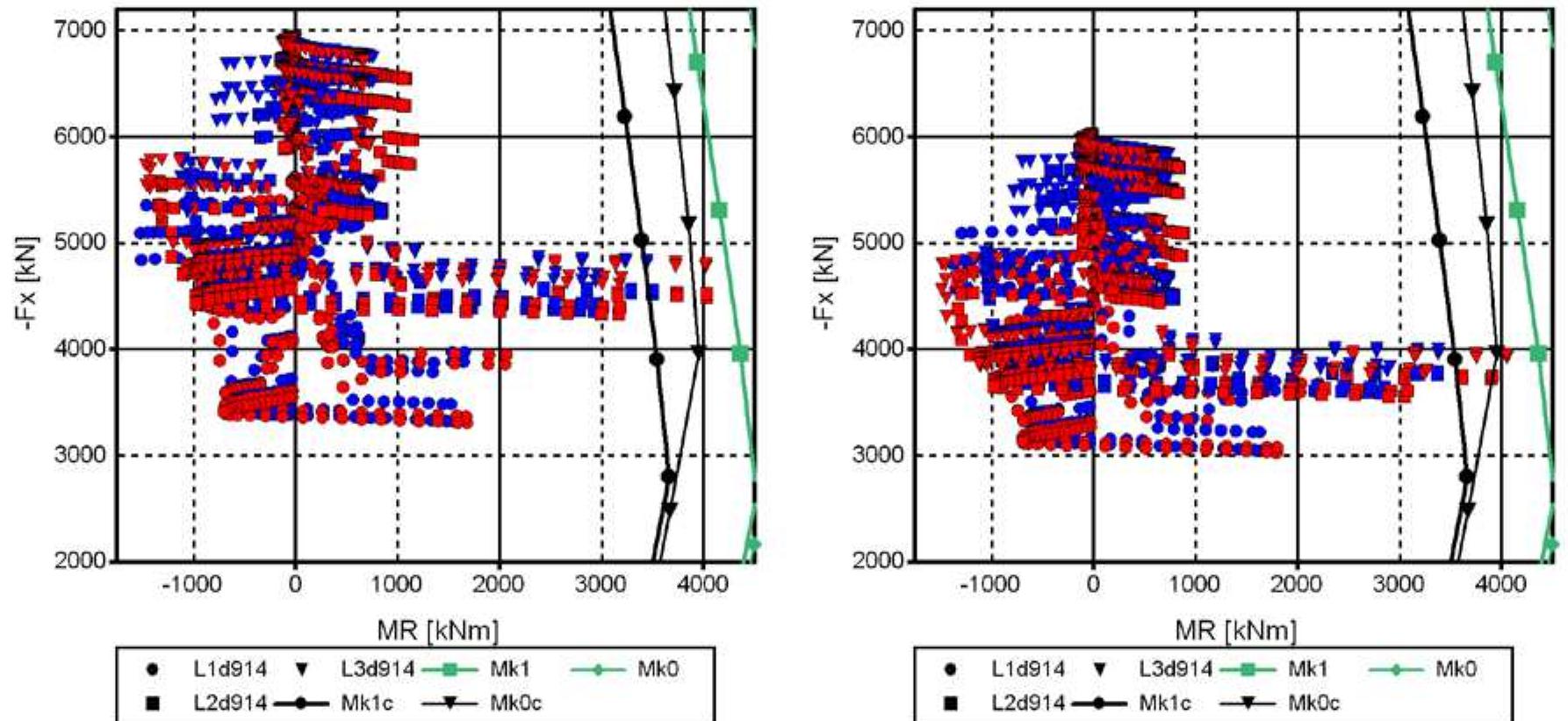

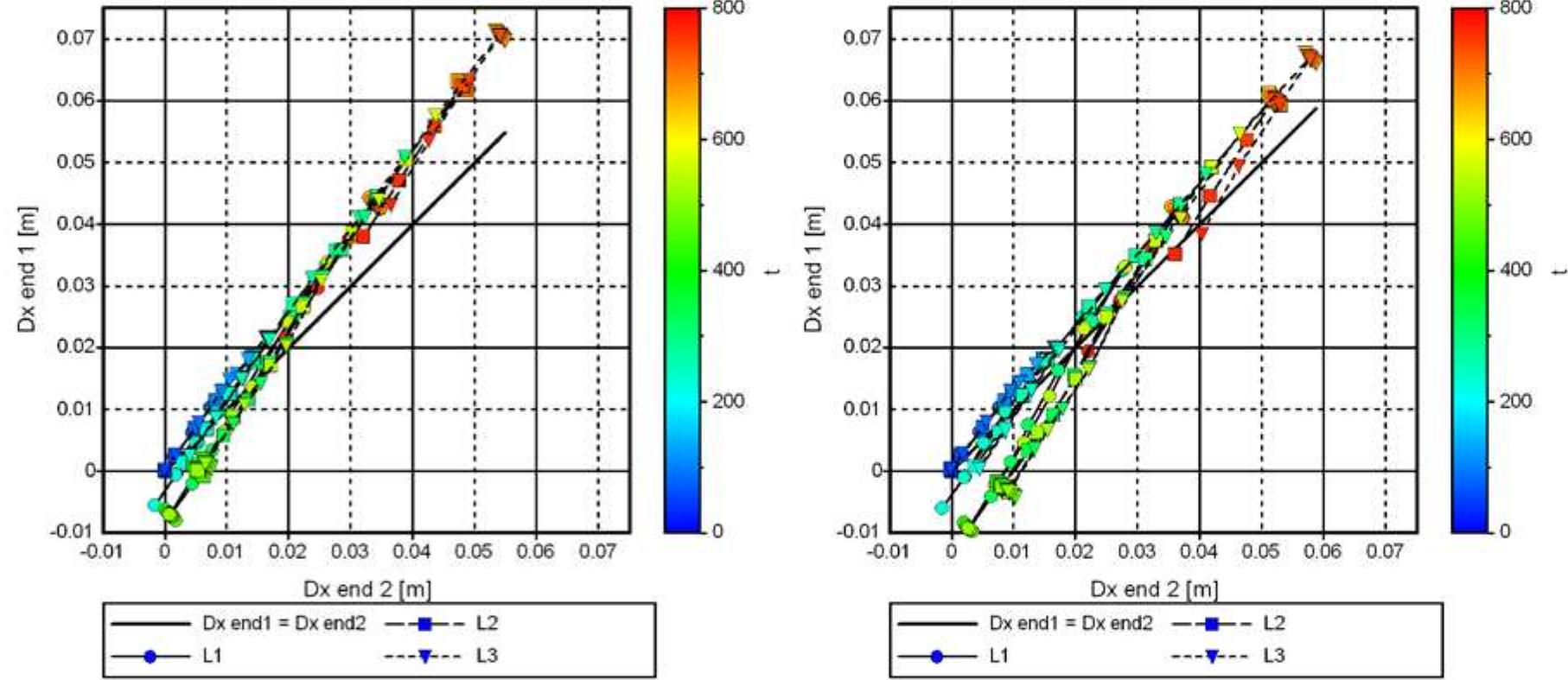

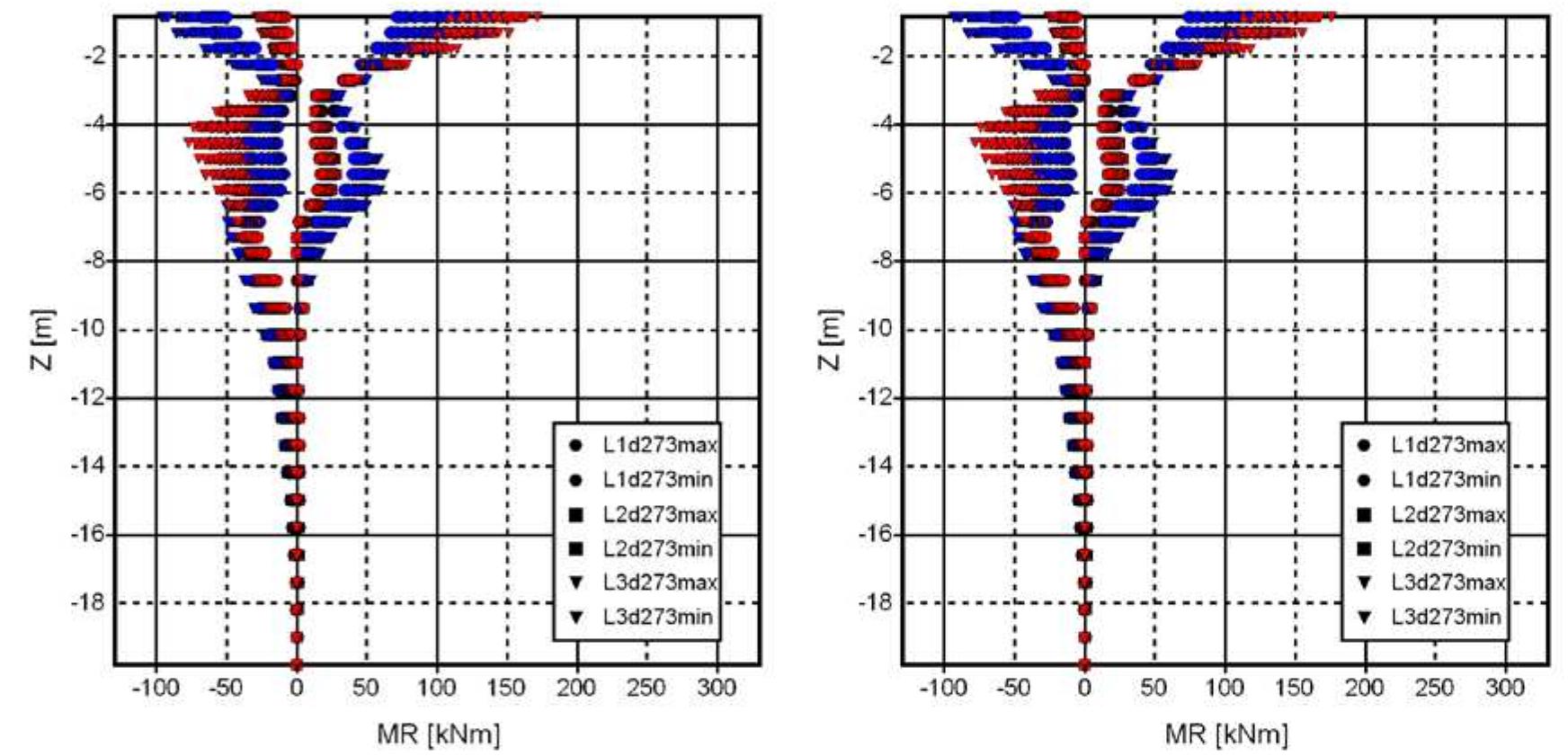

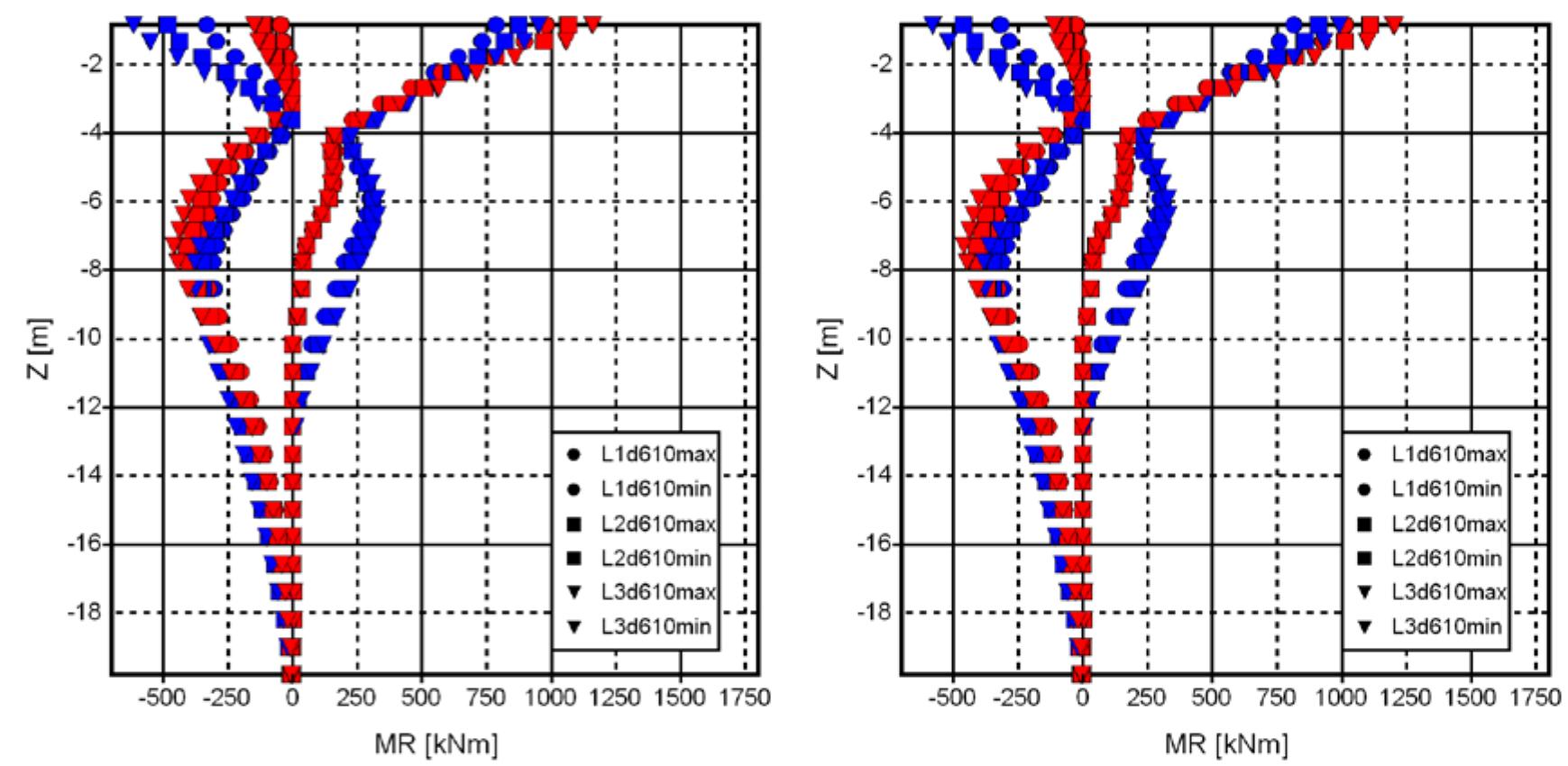

- i. Pile bending moments M R at top of pile from bridge mod- els B2_L1_S1_d914 and B3_L1_S1_d914, pp. 244-245 ii. Moment M y,end,tot from bridge models B2_ L1_S1_d914 and B3_ L1_S1_d914, pp. 245-247

- M R -Z, M R -F X and D X,end1 -D X,end2 diagrams from bridge models B1, pp. 248-252

- M R -Z, M R -F X and D X,end1 -D X,end2 diagrams from bridge models B2, pp. 253-257

- M R -Z, M R -F X and D X,end1 -D X,end2 diagrams from bridge models B3, pp. 258-262

- Analyses of preliminary reinforcement and bending stiffnesses of reinforced bridge superstructure, pp. 263-265

Related papers

Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2011

Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2004

Advances in Structural Engineering, 2005

Communications - Scientific letters of the University of Zilina, 2014

Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Bridge Engineering, 2018

MATEC Web of Conferences

European Earthquake Engineering Issn 0394 5103 1996 Vol X N 3, 1996

Bridge Structures, 2005

MATEC Web of Conferences, 2018

Journal of vibration engineering & technologies, 2019

Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering (COMPDYN 2015), 2019

nternational Conference on Mechanical Engineering 2011, 2011

Anssi Laaksonen

Anssi Laaksonen